Before I get to the main factors affecting time perception, I should talk about time-perception a little more generally. Humans are very accurate measurers of time at relatively short intervals (from milliseconds to minutes), with both the mean perceived time and the standard(the function of this relationship has a slope near 1 deviation of duration judgements varying linearly with elapsed time1. This second property (the linear relationship between duration and the standard deviation of duration judgements) indicates that time perception obeys Weber's Law, such that the absolute sensitivity of time judgements is independent of the length of the actual duration. Factors (in addition to those discussed below) that affect duration judgements include: the order in which stimuli are perceived (time-order errors), whether the interval is filled or empty (filled intervals are perceived as longer than empty ones), and the length of time between the event and the duration judgement (durations are remembered as having been longer if there is a delay in recall2).

In cognitive research, there are two general types of time-perception tasks. Participants are usually either asked to remember the duration of a particular event ("remembered duration"), in which case the participants do not learn that they must make a temporal judgement until after the event has occurred, or they are asked prior to the event to make a judgement about how long the event lasts ("perceived duration")3. Different factors affect performance in the two tasks differently, and research often consists in contrasting the effects of a particular IV on the two tasks. In neuroscience, the most common type of time-perception tasks are ones that require people to measure the timing of either a perceptual stimuli or the performance of a motor task, like those mentioned in the previous post, which are types of perceived duration tasks. Most of the research described below will use remembered or perceived duration tasks.

Attention

We've all had the experience of time flying when we are doing something interesting, or time dragging on when we are bored. For some time, psychologists have theorized that this is due to the sharing of attentional resources between the processing of the stimuli and the processing of temporal information. When a stimulus attracts a significant amount of attention, there is less attention available to process time. This results in a shortening of perceived duration judgements. When more attention can be given to temporal information, time judgements tend to be more accurate4. For instance, when participants were presented with interesting stories in a prospective judement task, they judged them to be shorter than stories of the same length that were less interesting5.

Of course, interestingness isn't the only thing that increases the amount of attention given to stimuli, and therefore taken from time processing. Thus, we would expect that the duration of difficult tasks would be perceived as shorter than the duration of easier tasks. To demonstrate this, in one experiment, researchers presented participants with either an easy or difficult stroop task. As predicted, the easier tasks were perceived as taking longer than the more difficult ones6. Similar effects have been found with syntactically ambiguous sentences (e.g., "Time flies like an arrow"). Ordinarily, remembered durations are judged to be shorter than perceived durations. However, in an experiment in which participants read syntactically ambiguous sentences, the relationship was reversed, with the perceived duration of reading times for those sentences being shorter than the remembered durations7.

As has probably become clear, attention does not affect remembered duration judements. This is because people tend not to pay attention to duration unless they are asked to, or the task is unusually dull ("How many more turns?"). Judgements of duration in remembered duration tasks are instead affected by things like changes in context, or changes in the ways that stimuli must be processed8.

Thus, there is ample evidence that attention-demanding stimuli (e.g., interesting or difficult tasks) affect perceived duration, but not remembered duration. The role of attention in perceived duration judgements is interesting, because it provides a point of contact betweenthe cognitive research and the neuroscientific. As I said in the previous post, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is active during duration judgement tasks. This brain region is also closely associated with attention, and one of the hypothesized roles of the DPC in time perception is that of allocating attentional resources to temporal information. The DPC is also responsible for the transmission of information about context changes to the hippocampus, a key structure in the storage of information in long-term memory. The transmission from the DPC to the hippocampus is likely automatic, and since this information is used to make remembered duration judgements, this automatic transmission explains why remembered duration judgements are not affected by the allocation of attention.

Modality

There are two main findings from research on the effects of modality on duration judgements: auditorily presented stimuli tend to be judged more accurately than visually presented stimuli, and when the durations of auditorily presented stimuli tend to be judged as longer than those of visually presented stimuli with equal actual duration. These findings primarily occur in perceived duration tasks. For instance, in a recent set of experiments, during a learning phase, participants were presented with either an auditory or visual stimulus of a target duration (400 ms). After the learning phase, they were presented with either a visual or auditory stimulus of the target duration, followed by test stimulus, and asked to indicate whether the test stimulus was of the same duration as the target duration. In the learning phase, participants were more accurate in judging auditory stimuli than visual ones, consistent with past research. In addition, the researchers found that when the learning phase and test phase stimuli were in different modalities (e.g., the duration is learned with visual stimuli, and tested with auditory stimuli), participants' accuracy dropped off significantly. In this case, participants tended to underestimate duration length. This is likely to do the increase in difficult of the task, resulting in the increased allocation of attentional resources9.

Arousal and Affect

Some psychologists have criticized the research on attention and time perception, because many of the experiments designed to show the effects of splitting attentional resources use stimuli that increase levels of arousal. This confound is difficult to remove, because the tests for increased mental load (the allocation of more attentional resources) also tend to be affected by levels of arousal. To test whether level of arousal can affect perceived duration judgements, Angrilli, et al.10 manipulated participants' arousal levels during stimuli presentation, and asked for duration judgements. In addition to arousal level, the emotional valence of the stimuli was also varied. Some stimuli carried a positive valence (with either high arousal, e.g., slides depicting sexual content, or low arousal, e.g., slides with photos of babies or puppies), while others carried a negative valence (with high arousal, e.g., humand wounds, or low arousal, e.g., spiders and rats). They found that arousal does affect perceived duration judgements, and that its effects differ depending on the emotional valence of the stimuli. When participants' arousal level was low, they tended to judge negative slides as having shorter durations, and positive slides as having longer durations. The effects were the reverse for high levels of arousal, with the durations of positive slides being underestimated relative to estimations of neutral slides, and the durations of negative slides being overestimated. Angrilli, et al. hypothesize that at low arousal, the allocation of attentional resources can affect time-perception, with negative slides receiving more attention, and therefore shorter duration estimations. However, attentional factors do not seem to be at play during high arousal judgements. The researchers hypothesize that this is due to the avoidance reactions caused by the negative stimuli. Since participants are unable to avoid those stimuli, they perceive the duration of their presentation as longer than it actually was.

As with attention, it appears that arousal level does not affect remembered duration judgements.The only direct test of this that I know of came from a study on the effect of caffeine on duration judgements. The study found that participants who were given caffeine consistently rated durations as shorter than participants who had received a placebo, in perceived duration tasks. However, caffeine had no effect on remembered duration11.

Temporal Language

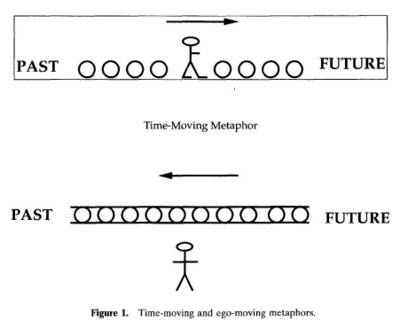

Thusfar, the discussion has been about judgements of stimuli presented for relatively short durations. At longer durations, conceptual factors come into play. For that reason, it might be interesting to talk about the role of spatial terms in talking about and conceptualizing time. I've written about this before (see here), but I quick rehash won't hurt. In most languages, the terms used for talking about time are borrowed from space. In English, for example, we talk about things being "before" or "after," events occur "from" a time "to" another time, and events even have "length." In general, for English speakers, there are two ways of conceptualizing time in terms of space (see figure): either we are travelling through time towards future events, or time is travelling from the future toward us. The ways in which we talk about temporal durations (e.g., "We are coming up on finals" vs. "Finals are fast approaching") can influence which of these conceptions we use to represent them 12.

From Gentner, et al (2002), p. 539

Interestingly, while both spatial conceptions of time involve horizontal motion, Mandarin speakers use vertical terms to describe temporal relations. Even when speaking in English, individuals whose first language was Mandarin tend to conceptualize time verticallyl13. This indicates that there exist linguistic and cultural differences in time-perception.

1 Allan, L. G. (1979). The perception of time. Perception & Psychophysics, 26, 340-354.

2 Wearden, J., Parry, A., & Stamp, L. (2002). Is subjective shortening in human memory unique to time representations? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section B, 55, 25.

3 The terminology comes from Block R.A. (1990). Models of psychological time. In Block, R.A. (Ed.) Cognitive models of psychological time. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, p. 1-35.

4 Treisman, M. (1963). Temporal discrimination and the indifference interval: Implications for a model of the “Internal Clock”. Psychological Monographies, 77, n. 13.

5 Hawkins, M.F., & Tedford, A.H. (1976). Effects of interest and relatedness on estimated duration of verbal material. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 8, 301-302.

6 Zakay D., & Fallach, E. (1984). Immediate and remote time estimation – a comparison. Acta Psychologica, 57, 69-81.

7 Zakay, B., & Block, R. A. (2004). Prospective and retrospective duration judgments: an executive-control perspective. Acta Neurobiologiae Experimentalis, 64, 319-328.

8 Zakay & Block (2004)

9 Klapproth, F. (2001). The effect of modality on retrieval of subjective duration from long-term memory. Fechner Day 2001. In E. Sommerfeld, R. Kompass, T. Lachmann (Eds.). Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Meeting of the International Society of Psychophysics, 456-461.

10 Angrilli, A., Cherubini, P., & Pavese, A. (1997). The influence of affective factors on time perception. Perception & Psychophysics, 59(6), 972-982.

11 Gruber, R. P., & Block, R. A. (2003). Effect of caffeine on prospective and retrospective duration judgements. Human psychopharmacology: clinical and experimental, 18(5), 351-359.

12 Gentner, D., Imai, Mutsumi, & Boroditsky, L. (2002). As time goes by: evidence for two systems in processing space-time emtaphors. Language and Cognitive Processes, 27(5), 537-565.

13 Boroditsky, L. (2001). Does language shape thought? English and Mandarin speakers' conceptions of time. Cognitive Psychology, 43(1), 1-22.

55 comments:

Post a Comment