An entrée of Cognitive Science with an occasional side of whatever the hell else I want to talk about.

Tuesday, January 25, 2005

Light Posting This Week

Monday, January 24, 2005

Summers for the Last Time

Rather than genetics, doesn’t it seem more likely that the tenured faculty in science departments are overwhelmingly male for the same environmental reasons which explain why most English departments have at least as many tenured men as women? [Researchers have consitently shown that females have higher verbal scores. - Chris] Men in our society improve their standing vis-a-vis women in all disciplines from high school and college to professional life. When men start with a slight advantage, they wind up with almost total control. When men start with a severe disadvantage, they obtain equality, if not some advantage. This is culture, not genetics, unless one assumes the genetic effects of masculinity only kick in around age 25. This notion, obviously absurd, also contradicts medical observations that genetic predispositions generally begin to exert their influence early in life.I raised the point in my first post on Summers that he was wrong to emphasize what are likely to be small influences that we can do nothing about over potentially large influences that we can do something about. I still think that is the primary reason Summers was wrong. The fact that so many defenders of Summers, from Pinker to the folks at Volokh, keep talking about the existence of sex differences, indicates to me that they fail to understand that.

Sunday, January 23, 2005

Everybody's an Expert: When Cognitive Science Goes Public

You're probably wondering, what brought all this on. Well, I'll tell you what brought all this on. This did! Now, I assume that Todd Zywicki is a fairly intelligent guy. He's on the faculty at what, for all I know, is a good law school. Yet, it appears even this career intellectual isn't immune to the, "I know how my mind works" syndrome when it comes to evaluating cognitive science research. If you follow that link, you will find one of the most intellectually vapid critiques of a scientific research program ever. Zywicki demonstrates quite well that he knows nothing about IAT or implicit attitude research, writing nonsense like:

Is it really plausible that my impression of Bill and Hillary is driven more by whether I have a messy desk than my personal perception that Bill Clinton is a liar and Hillary Clinton is a megalomaniac and opportunist?No, it's not, Todd, but that's now what the IAT is about. The IAT is about stable attitudes that may not be measurable through explicit measures (which is not to say that they are never measurable explicitly, another misunderstanding Todd seems to have), not ephemeral attitudes that are based on things as irrelevant as how organized your desk is at the moment. I don't know if such attitudes exist, but if they do, the IAT was not designed to discover them.

Now, I'm no fan of the IAT (as I've said before), but my problems with it are methodological. Other implicit tests that avoid the IAT's methodological problems (e.g., evaluative movement assessment) have also shown that implicit attitudes (or evaluations, or valences, or whatever you want to call them) do in fact exist, can be measured, and correlate quite nicely with several behaviors. Now, neither the IAT nor EMA can tell us where these evaluations come from, but that's not their goal. The fact remains that a lot of rigorous research has demonstrated the existence of such attitudes or evaluations, and Todd's disbelief in them doesn't amount to anything like a critique of that research.

Yet, Todd thinks, so he assumes he's qualified to talk about thinking. I wonder, if a physicist had conducted some research that produced a finding that Todd disagreed with, but Todd had not bothered to read up on the actual research, would he write a post calling it absurd? I mean, Todd has existed in the physical universe for as long as he can remember (I'm assuming, of course, that Todd hasn't had any major bouts of psychosis in the past), so he should be able to comment on any findings that concern that universe, right?

My real suspicion is not that Todd doesn't like the IAT. He knows shit about it, so how could he not like it? What I really think is that Todd doesn't like the idea that much of his mental life goes on below the level of his awareness. That's not surprising. I'd bet that a lot of people dislike the idea of that. So, Todd lashes out at a methodology, an area of research, and an entire scientific field, because he's uncomfortable with the truth. I just have to keep reminding myself that this is one of the hazards of my chosen field. When you study something people already think they're experts on, you're going to have to deal with stupidity sometimes. I suppose I should thank Todd for reminding me of that.

(Link to Zywicki's post via Universal Acid, who also thinks the criticisms are stupid.)

UPDATE: In an update at the end of his post, Zywicki responds to my criticisms, and those of Andrew at Universal Acid. I'll ignore the fact that he endorses evolutionary psychology (which is never a good sign), and focus on the remarks that are actually relevant. He writes:

I think the study of cognition and unconscious reasoning is very useful and explains much. I just think that it is important in studying this, as with everything else, that we remain aware of the limitations of the work and, in particular, make sure that the conclusions and implications we draw are actually supported by what the experiments are actually calibrated to test.Of course, this is what IAT researchers, and others in the field are already doing, and nowhere does Zywicki provide evidence that they are not "Aware of the limitations of the work" or "[making] sure that the conclusions and implications we draw are actually supported by what the experiments are actually calibrated to test." Of course, as I've noted, there may be problems with inferences of "prejudice" from the IAT, but there is still a debate going on about that, and since Zywicki neither references that debate or any of the evidence, his criticisms seem misguided.

Zywicki also confirms my suspicion that his real beef is with the idea that many of his attitudes may have unconscious sources, as he writes:

Clearly many of my beliefs and actions are motivated primarily by my subconscious, equally clearly to me many of my other beliefs and actions are motivated primarily by my conscious, and most is in-between. I recognize that my love for my family or the Pittsburgh Steelers is heavily rooted in my subconscious mind; but I also find it much more likely that my slight preference for Bill versus Hillary Clinton has a lot more to do with my conscious.The problem is that what research like that on IAT, EMA, goals and evaluations, source monitoring, conscious will, and automaticity has demonstrated is that Zywicki is in no position to determine the extent to which the sources of his attitudes are conscious or unconscious. He can, of course, consciously access his attitudes towards Bill and Hillary, but their sources may (in fact probably do) allude him. That he insists on denying this, without reference to any evidence, only exacerbates my frustration with yet another non-expert who feels qualified to speak with authority on issues he knows little or nothing about.

Which brings me to Zywicki's dumbest remark of all, the one with which he justifies criticizing the work despite his ignorance of it. He compares IAT to astrology, writing:

Do I have to be an expert in the "science" of horoscope reading in order to reject the proposition that "the stars" are in control of my life? I think not.No, Todd, but you should at least be aware of the differences between science (which IAT research is, and you've offered no reasoned argument to the contrary) and astrology, before comparing the two.

UPDATE II: Zywicki responds again, this time in an entirely new post (once again, via Andrew of Universal Acid, who happens to have added an update to his original post as well). The gist of Zywicki's argument, which he originally used in an email to me, is that if most of the sources of our attitudes are not available to awareness, then it's likely that his (and my) attitudes toward the IAT are not available to awareness, and therefore there's no reason for me, or Andrew, or anyone else to try to convince him to change his mind. In making this argument, Zywicki once again indicates a complete ignorance of cognitive psychology, and I promise you that because he insists on commenting out of complete ignorance, this will be my last attempt to address his "arguments." To do so, I will clarify a few things:

1.) Just because we are aware of, or consciously guiding, our reasoning on a particular topic, doesn't mean that our reasoning cannot be influenced by unconscious processes, associations, and attitudes (valences). In fact, the information of which we are consciously aware is largely the product of unconscious processes which produce a coherent and generally verbalizable (except, of course, in the case of some aspects of visual consciousness) output. Put differently, the information of which we are consciously aware has been polished by unconscious processes, which have largely determined their content.

2.) Just because we are not aware of our cognitive processes and representations (in part or in their entirety), doesn't mean that information of which we are aware (e.g., arguments or facts that others communicate to us) can't influence those processes or representations. In most cases, complex conceptual information must be attended to be processed, and that means we're probably going to be aware of that information, at least while we're encoding it (i.e., while it's present in working memory).

3.) Just because we are consciously aware of our attitudes, behaviors, etc., and perhaps even have some conscious idea of our reasons for them (or consciously reason about them), doesn't mean that the ultimate attitudes, behaviors, etc. are in fact the product of conscious thought. As Dan Wegner has shown over and over again, our inferences of conscious will or forethought are often mistaken.

4.) Just because our ideas are the products of unconscious processes doesn't make them any less rational. If we had evolved to have a largely irrational cognitive system that is supplemented by a fairly small, rational component, we wouldn't have lasted very long. In fact, I would argue that in many cases, the unconscious processes are more likely to be rational (in the behavioral sense, which means something like "optimal") than those that are influenced by conscious thought. Consider a basketball player who is shooting free throws. Most of the time, he does so "unthinkingly," which is to say, utilizing wholly automatic and largely unconscious processes. Occasionally (especially if he's missed a few in a row) however, he will start to "think" about the shots, and reason about how to shoot free throws consciously. His accuracy will almost certainly decrease when he does this, because the automatic processes have been honed through years of practice, and all the conscious reasoning does is interrupt those processes. Zywicki is likely to object that this example isn't quite like his well-reasoned, conscious beliefs about the Clintons, and he'd be right, to some degree, but he'd also be missing the larger point. The unconscious mind isn't some Freudian playground in which nefarious drives and forces produce beliefs and attitudes willy nilly, with no justification. The unconscious mind is dominated by processes that have been honed through millions of years of evolution, and years of life experience, to produce actionable, adaptive outputs.

5.) While it's understandable that Zywicki would hold an antiquated view of the mind, since he's clearly unacquainted with any psychology literature whatsoever, it is not clear why he holds one particular misconception, namely his belief that the IAT only measures unconscious attitudes. Nowhere on the IAT site, or in any of the various publications on IAT in the peer reviewed literature, is this claim made. The word "implicit" in "Implicit Attitude Test" denotes the nature of the test, and not necessarily that of the attitudes it is supposed to be measuring. If Zywicki had actually read the Project Implicit website, he would have learned this, and perhaps even learned that the use of implicit tests is necessitated by the problems involved in getting people to report their attitudes when those attitudes may be socially undesirable. It is true that the IAT people tend to believe that some, and perhaps many attitudes are implicit, and the empirical evidence supports that belief, but critiquing that belief does not count as a criticism of the IAT.

Saturday, January 22, 2005

How to Compromise Everything to Get Votes

- An Immigration Moratorium: Let's let the xenophobia that is rampant in some red states win over, by not letting any new people in. Forget, for a moment, that we were all once immigrants. This is needed "to give this country a chance to assimilate the 30 million foreign-born citizens we already have." What, exactly, assimilation means I do not know. Perhaps it's only an economic assimilation, but the potential connotations are scary.

- A National ID: In order to prevent illegal immigration and guard against terrorism, we should place a serious threat on peoples' civil rights by issuing them papers... er national IDs, "without which a person cannot cash a check, use a credit card, sign a lease, take a job, get a driver's license, open a bank account, enroll in school, or otherwise function in our society." (Emphasis mine). Don't be concerned about the impracticality of such an ID, or even the Big Brother-esque implications of a document that allows the government to track your movements at every turn. The Born Again Democrats have an answer for such concerns: "Concerns about civil rights in this context seem misplaced and overblown. The ACLU needs to grow up." Now that's an argument!

- Marriage Amendment: Recognizing that one of the primary reasons many Democrats (especially southern Democrats) left the party, and started voting Republican, in the 50s and 60s had to do with the Democratic party's emphasis on tolerance and civil rights, the Born Again Democrats believe we should get rid of both, and support an amendment to the federal constitution that defines marriage as a union between "one man and one woman," and thus outlawing gay marriage nationwide. As their definition of marriage indicates, they also don't like polygamy, writing, "So in these two instances, at least, multi-culturalism be damned!" At least.

- Put an End to Racial Preferences: Study after study has shown that in the absence of programs that are not race-neutral, minorities are at a significant disadvantage, particularly in the business arena, which is why the courts have consistently upheld affirmative action laws. But do we care? Not anymore, because rural red-state white men don't like that African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, or women might be able to compete with them for jobs and contracts once the playing field is leveled. So, let's do our best not to level it, and maintain the white male status quo.

- Community Standards: This one deserves to be quoted in its entirety:

We support a re-interpretation of the First Amendment to exclude the protection of sexually graphic images and obscene language. The purpose of freedom of speech and of the press is to allow open debate of controversial ideas, such as we are engaging in right here. It was never intended to abolish small-town standards of decency and public decorum, let alone enable profit-making entities to pump hardcore pornography into every home and library in America. Let the local majorities decide! A place for everything, but everything in its place!

Apparently adopting the Republican social agenda requires adopting the Republican penchant for hyperbole. Pornography is in "every home" and "every library" in America? One wonders what they mean by pornography, in this case. Even if we include porn spam (which you have to open, click on, and then click on some more, to see), it's not easy to argue that porn is being forced on anyone, but we're not beholding to reality anymore. - Teaching the Bible in Schools: Consistent with their reinterpretation of the First Amendment, the Born Again Democrats want to teach the Christian Bible in public schools. They write:

We favor not just allowing but requiring the Bible to be studied in our public schools as an integral part of the history curriculum.

"Not just allowing but requiring!" I'm all for noting the role, however limited, that Christianity played in the formation of our founding documents, as well as discussing the influence of Christianity on American history. I'm pretty sure this is already done (how many people don't know that the Puritans left England because of religious persecution, that Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers, or that Maryland was so-named because of the Catholics who settled there?), but the Born Again Democrats don't think this is enough. They want to teach the Bible! Who cares that doing so is a blatant violation of the First Amendment (remember, we're reinterpreting it), or that teaching the Bible is likely to provide no insight whatsoever into American history, or world history in general. That's not the point. We want to teach the Bible, and it's a historical document, so it should be taught as part of the history curriculum.

UPDATE: More on National IDs at Doing Things With Words.

The Cognitive Science of Art: Ramachandran's 10 Principles of Art, Principles 4-10

- Peak shift

- Perceptual Grouping and Binding

- Contrast

- Isolation

- Perceptual problem solving

- Symmetry

- Abhorrence of coincidence/generic viewpoint

- Repetition, rhythm and orderliness

- Balance

- Metaphor

Isolation

Ramachandran's first three principles, peak shift, grouping, and contrast, may, after a little thought, seem fairly obvious. Art is generally not meant to be strictly representational, but instead to highlight a particular viewpoint, or series of viewpoints, and amplify the features derived from those viewpoints. This is, in essence, the peak shift principle. In addition, artists are generally masters at guiding our visual attention, and the methods of grouping and contrast are exellent ways to do this. His third principle, however, may strike many as counterintuitive, but as he himself notes, it ultimately fits with a common artist's maxim: "Less is more."

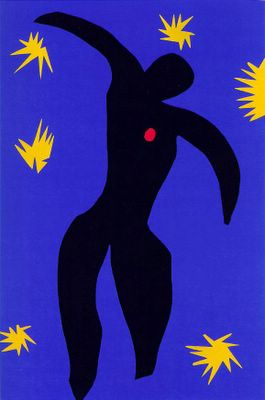

Henry Matisse, "Icarus (Jazz)."

The third principle, isolation, refers to "the need to isolate a single visual modality before you amplify the signal in that modality" (from RH). RH use the example of an outline drawing (or something similar, like the Matisse above), arguing that it is more aesthetically pleasing than a photograph, because it isolates one visual modality, in this case form (think also of a Robert Morris or Ellsworth Kelly sculpture, or other works by minimalists), which allows for the allocation of more attention to that modality. They write:

[T]here are obvious constraints on the allocation of attentional resources to different visual modules. Isolating a single area (such as ‘form’ or ‘depth’ in the case of caricature or Indian art) allows one to direct attention more effectively to this one source of information, thereby allowing you to notice the ‘enhancements’ introduced by the artist. (And that in turn would amplify the limbic activation and reinforcement produced by those enhancements).Presumably any visual modality (e.g., color, depth, luminance, etc.) could be isolated to produce a stronger aesthetic experience. A single work of art need not highlight only one modality, but the more attention we can allocate to any given modality, the more pleasurable the experience should be.

As evidence for this principle, Ramachandran (here and here) uses as examples stroke patients and an austistic child named Nadia who have damage to most areas of their brain, but whose right parietal lobes are largely intact. In stroke patients who fit this description, artistic abilities that they had not previously had often develop suddenly. Nadia is severely retarded, but she is capable of producing vivid drawings that are far more sophisticated and aesthetically pleasing than other children her age. Ramachandran argues that this is because one of the right parietal lobe's functions is artistic perception, and the ability to allocate all of one's attention to this area (due to the fact that so many other areas of the brain are damaged) allows these stroke patients and Nadia to produce exceptional works of art. In fact, autistic savants, even those whose brains are not as severely damaged as Nadia's, are often able to produce vidid works of art. RH argue that this is consistent with theories of autism in which the autistic mind tends to allocate all of its attentional resources to one channel, to the exclusion of others that may be relevant, as well as theories that argue that the lack of conceptual processing in autistics allows them to process visual information better.

The isolation principle is the one for which Ramachandran and Hirstein offer the most novel predictions, and therefore may be the easiest to test directly. Here are a few of those predictions:

If you put luminous dots on a person’s joints and film him or her walking in complete darkness, the complex motion trajectories of the dots are usually sufficient to evoke a compelling impression of a walking person—the so-called Johansson effect (Johansson, 1975). Indeed, it is often possible to tell the sex of the person by watching the gait. However, although these movies are often comical, they are not necessarily pleasing aesthetically. We would argue that this is because even though you have isolated a cue along a single dimension, i.e., motion, this isn’t really a caricature in motion space. To produce a work of art, you would need to subtract the female motion trajectories from the male and amplify the difference. Whether this would result in a pleasing work of kinetic art remains to be seen. (From RH)

[O]ne might predict that if you record from master ‘face cells’ in monkeys they might actually respond better to outline drawings than to half tone photos even though the latter have ‘more information’ (assuming that the masking by irrelevant attributes occurs earlier than the neuron’s response). The extra information is not part of the defining attribute of the face—only the outline is. Lastly if you obtain GSR (galvanic skin response) from humans or do non-invasive brain imaging you should see a bigger signal (either on the palm or in the fusiform brain area) for outline drawings of faces than would be the case with half tone photos— and an even bigger response if the drawing is also subjected to peak shift, caricature or exaggeration. (from Ramachandran's interview).I don't know that anyone has conducted such experiments (if they have, they haven't published them, which means they may not have worked), but the fact that Ramachandran is able to derive these predictions is indicative of the strength of the neuroaesthetic approach, and in keeping with its goals.

One more note on the principle of isolation. You may be thinking that it is similar to the peak shift principle. Recall that the peak shift principle involves the exaggeration of certain visual features. One way to strengthen the peak shift effect would be to isolate a single visual modality and exaggerate features in that modality, as, for example, the stick with three red lines isolates the color red from the chick's mother's beak, and then exaggerates them. One might argue that this is what Van Gogh has done with color in many of his later paintings, in which the entire form of the painting is defined by exaggerated color.

Vincent Van Gogh, "Cafe Terrace on the Place du Forum."

Perceptual Problem Solving

As I said in the previous post, Ramachandran argues that discovering a signal in noise is rewarding in itself. For this reason, we derive pleasure from extracting an image from a noisy background (recall the picture of the dalmation). In addition to doing this through grouping, we also use completion and other tools of the visual imagination. We combine elements, and search for ways to put sometimes disparate elements together. RH argue it is this that explains why a nude behind a veil is more appealing than an image of a woman nude in the open (or, to use Ramachandran's examples from the BBC lecture, " a full-colour Playboy photo or a Chippendale pinup"). We have to imagine the rest of his or her form, and in doing so, our visual system continually inputs to the limbic system, producing a continuous reward in order to keep us motivated. RH put it this way:

[A] puzzle picture (or one in which meaning is implied rather than explicit) may paradoxically be more alluring than one in which the message is obvious. There appears to be an element of ‘peekaboo’ in some types of art — thereby ensuring that the visual system ‘struggles’ for a solution and does not give up too easily.

Marcel Duchamp, "Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2."

This may explain the appeal of much of Picasso's work, or the work of the surrealists (e.g., the Duchamp painting above), in which the meaning or form is often elusive, forcing us to search for it. The search itself is rewarding, and thus part of what produces the aesthetic experience we get from such art.

Symmetry

It's well known that both facial1 and body2 symmetry are generally considered attractive, though the role of symmetry in attractiveness may not be as large as previously thought3.In fact, symmetry can give us a great deal of information about the environment, such as the presence of biological forms (which are usually symmetrical) and human-created artifacts. It's not surprising, then, that we find symmetry appealing in art. RH write:

Since most biologically important objects — such as predator, prey or mate are symmetrical, it may serve as an early-warning system to grab our attention to facilitate further processing of the symmetrical entity until it is fully recognised. As such, this principle complements the other laws described in this essay; it is geared towards discovering ‘interesting’ object-like entities in the world.Thus, much as with grouping, contrast, and perceptual problem solving, art that uses symmetry (like the Escher drawing below) takes advantage of the fact that symmetry itself is rewarding in order to motivate us to allocate more resources to objects that exhibit it.

M.C. Escher "Up and Down."

Abhorrence of Coincidence/Generic Viewpoint

The human visual system is a Bayesian deduction machine. There are Bayesian models of virtually every aspect of lower and higher-level vision (if you don't believe me, go to any article database, and use the keywords Bayesian and vision). This means, among other things, that out of all of the possible interpretations of a particular visual input, the visual system will pick the most likely. This has two implications, which Ramachandran uses to formulate another principle of art: we prefer generic viewpoints, and we abhore coincidence. To understand the first part, the preference for generic viewpoints, consider the following two figures from RH:

As the caption notes, we automatically intepret Figure A as depicting one figure partially occluding another, instead of the two objects in B. This is because, while there are multiple viewpoints from which the image in A might be produced through occlusion, the objects in B could only produce it from one viewpoint.

The next two figures from RH help to illustrate the "abbhorence of coincidence":

In A, the palm tree's placement is suspiciously coincidental with the positioning of the pyramids, while B seems much more natural, with the palm and pyramids offset. Suspicious coincidences are suspicious because they are highly unlikely, and therefore our visual system tends not to like them. Thus, they and unique viewpoints are less rewarding.

This is one principle about which RH are quick to note that there may be violations that are appealing, perhaps because they utilize one of the other principles. For instance, the Picasso paintings discussed as examples of the peak shift principle in art, which utilize multiple viewpoints at one, produce several suspicious coincidences, and highly unique viewpoints, but their utilization of peak shift, and perhaps other principles like isolation or perceptual problem solving, makes them pleasing.

Metaphor

While Ramachandran lists metaphor as a principle of art on all of his lists, he doesn't really explain any neurological reasons for including it. He and Hirstein write:

Whether [metaphor] is purely a device for effective communication, or a basic cognitive mechanism for encoding the world more economically, remains to be seen. The latter hypothesis may well be correct. There are many paintings that instantly evoke an emotional response long before the metaphor is made explicit by an art critic. This suggests that the metaphor is effective even before one is conscious of it, implying that it might be a basic principle for achieving economy of coding rather than a rhetorical device.I, however, think there are good reasons for including this as a principle of art that is based on fundamental cognitive principles. Therefore, everything I'm going to say here about metaphor is my own, and you should not blame Ramachandran for it.

Much like the visual system is designed to notice groupings, contrasts, and to be excited by exaggeration, our cognitive system is designed, at all levels (including the perceptual) to notice connections between inputs. You might say that we have "analogical minds." It's likely that in order to facilitate the search for such connections, finding them is itself rewarding, and thus may contribute to the pleasureable experience that many visual metaphors elicit. However, metaphor and analogy (of which metaphor is likely a special case) also allow the artist to activate a wide range of images, concepts, and experiences, sometimes vivid ones, which carry with them their own affective appeal. There is evidence, for instance, that poetry using vivid perceptual metaphors is more appealing than poetry using less vivid metaphors. One of RH's examples illustrates this well. They write:

This is also true of poetic metaphors, as when Shakespeare says of Juliet, ‘Death, that has sucked the honey of thy breath’: the phrase is incredibly powerful well before one becomes consciously aware of the hidden analogy between the ‘sting of death’ and the bee’s sting and the subtle sexual connotationsof ‘sucking’ and ‘breath’."Sucking" and "honey" are vivid perceptual images, and when combined with the strong emotions elicited by the concept of death, they produce a very intense experience in the context of Shakespeare's story. Consider also Archibald MacLeish's description of poetry, in which he uses the following metaphor:

Silent as the sleeve-worn stoneThe image itself is vivid (not simply of a stone, but one that is worn by the sleeves of many arms resting upon it), and allows MacLeish to say much more about poetry than he actually says. In a sense, then, the work of art, through metaphor, is less a statement with its own meanings, but a sign that points to many meanings, and their associated affects, which thus allows the work to produce a more powerful aesthetic experience. As MacLeish wrote:

Of casement ledges where the moss has grown--

A poem should not mean1 Perrett, D.I., Burt, D.M., Penton-Voak, I.S., Lee, K.J., Rowland, D.A. & Edwards R. (1999). Symmetry and human facial attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 20, 295-307.

But be.

2 Tovée, M.J., Tasker, K., & Benson, P.J. (2000). Is symmetry a visual cue to attractiveness in the human female body? Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 191-200.

3 Thornhill, R., & Gangestad, S. W. (1999). Facial attractiveness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3(12), 452-460.

Friday, January 21, 2005

Sponge Bob Is Brainwashing Your Children!

Now, Dr. Dobson said, SpongeBob's creators had enlisted him in a "pro-homosexual video," in which he appeared alongside children's television colleagues like Barney and Jimmy Neutron, among many others. The makers of the video, he said, planned to mail it to thousands of elementary schools to promote a "tolerance pledge" that includes tolerance for differences of "sexual identity."Scandalous! Sponge Bob being used to promote tolerance? Clearly, this is a message our children should not be exposed to!

But wait a minute, could it be that Dobson's attack is based on a misunderstanding (imagine that!)? It could. The videos creator sets the record straight:

Perhaps Dobson should have watched the video, though I'm not sure that would have swayed him or his legions. Despite Rogers' clarifications, Dobson and other whack jobs are continuing to object to the video.The video's creator, Nile Rodgers, who wrote the disco hit "We Are Family," said Mr. Dobson's objection stemmed from a misunderstanding. Mr. Rodgers said he founded the We Are Family Foundation after the Sept. 11 attacks to create a music video to teach children about multiculturalism. The video has appeared on television networks, and nothing in it or its accompanying materials refers to sexual identity. The pledge, borrowed from the Southern Poverty Law Center, is not mentioned on the video and is available only on the group's Web site.

Mr. Rodgers suggested that Dr. Dobson and the American Family Association, the conservative Christian group that first sounded the alarm, might have been confused because of an unrelated Web site belonging to another group called "We Are Family," which supports gay youth.

"The fact that some people may be upset with each other peoples' lifestyles, that is O.K.," Mr. Rodgers said. "We are just talking about respect."

Maybe Dobson just doesn't like disco. With all that touching and undulating, disco dancing is pretty salacious! I've heard that there may have been some gay people who liked, or even performed, disco music, too.

Dobson once again reminds us that there are evangelicals that we don't want.

Yet Another Plea for Requests

Right now, I'm working on the art stuff, and I will eventually post on some more issues related to attention and consciousness, with the hope of eventually discussing some of my own views on consciousness, but in the meantime, I'm more than willing to post on whatever it is you are curious about. So, let me know what that might be. Also, if you have any other suggestions, feel free to write me about those, too.

Thursday, January 20, 2005

The Cognitive Science of Art: Ramachandran's 10 Principles of Art, Principles 1-3

- Peak shift

- Perceptual Grouping and Binding

- Contrast

- Isolation

- Perceptual problem solving

- Symmetry

- Abhorrence of coincidence/generic viewpoint

- Repetition, rhythm and orderliness

- Balance

- Metaphor

Peak Shift

The concept of peak shift is probably familiar to some of you. First demonstrated in pigeons1, the peak shift effect occurs when an animal is rewarded for responding to a particular stimulus (the S+ stimulus, for positive stimulus), and not rewarded for responding to another (S-, for negative stimulus). After the training phase, the animal is tested with a range of stimuli to test for generalization. The animal will, of course, respond to S+, and not respond to S-, but surprisingly, the animal will respond the most to stimuli that are further from S- on the dimension(s) on which S+ and S- differ. For example, if pigeons are rewarded for responding to a flash of light of a particular wavelength (e.g., S+ = 550 nm), and not rewarded for responding to wavelengths higher than S+, then during the testing phase, they will respond the most vigorously to wavelengths under S+, with the size of the response increasing as the wavelength decreases. For another example (from Ramachandran and Hirstein) that might make the role of peak shift in art more clear, consider rats that are trained to respond to rectangles, and not to squares. Since rectangles and squares differ on a single dimension (e.g., width or height), then rats trained to respond to a rectangle of a certain length will respond more vigorously to rectangles of even greated width (or height, depending on the original stimulus).

Ramachandran and Hirstein (RH) compare the peak shift effect to the Sanskrit word "rasa," which is loosely translated as "essence." The peak shift involves the extraction of the "rasa" of a particular shape, color, etc. For example, consider the Hindu sculpture below. RH argue that the artist has abstracted the female body shape, and exaggerated it in a direction that takes it away from the male body shape, thus making the sculpture more aesthetically pleasing.

From Ramachandran's BBC Lectures, Lecture 4.

This explanation actually fits nicely with research on face and body attractiveness. There researchers have found that in some contexts (e.g., during periods of high fertility), women find artificially produced faces with exaggerated masculine features more attractive than normal or "average" faces (usually eigen-faces)2. In addition, participants find exaggerated female or male bodies more attractive than the real bodies rated most attractive, and exaggerated female bodies with male features, or male bodies with female features, are rated as the least attractive (see this PPT presentation).

Another example that RH use to illustrate the peak shift effect in art is the work of François Boucher, and his nudes in particular (see the painting below). RH argue that Boucher exaggerates the rosey hue in the womens' skin color, making them more attractive than figures with normal hues. They write:

[T]he primate brain has specialized modules concerned with other visual modalities such as colour depth and motion. Perhaps the artist can generate caricatures by exploiting the peak shift effect along dimensions other than form space, e.g., in ‘colour space’ or ‘motion space’. For instance consider the striking examples of the plump, cherub-faced nudes that Boucher is so famous for. Apart from emphasizing feminine, neotonous babylike features (a peak shift in the masculine/feminine facial features domain) notice how the skin tones are exaggerated to produce an unrealistic and absurd ‘healthy’ pink flush. In doing this, one could argue he is producing a caricature in colour space,particularly the colours pertaining to male/female differences in skin tone.

François Boucher, "Nude on a Sofa"

The Hindu scuplture and Boucher painting illustrate examples of exaggeration, or peak shift, that are easily identifiable. However, it may not always be possible to identify what is being exaggerated in art. This is not a problem for the theory, however. RH mention the example of seagull chicks, which instinctively peck at their mother's beak, which has a bright red spot at the tip. Researchers have shown that seagull chicks will also peck at a stick with a red dot at the end. Suprisingly, they will peck the most (when compared to the mother's beak and the stick with the red dot) at a stick with three red stripes. This stick bears no resemblance to their mother's beak, but the exaggeration of the relevant features (the red) produces an extreme response. RH call this last stick an "exaggeration in beak space," and argue that it is a "super-stimulus" that is the seagull equivalent of a Picasso. Concerning the human version of a Picasso, then, Ramachandran believes that Picasso's combination of two views of one face in a painting serve as a similar super-stimulus. In an interview, Ramachandran put it this way:

When a convergence of axons from several ‘regular’ face cells occurs on a single master cell, nature (or evolution) is not going to go through all the trouble of ensuring that the convergence results in a perfect ‘OR-gate’. On the contrary it may well be that if both views are simultaneously presented to the master cell then the converging inputs from the two corresponding regular ‘single view’ cells may simply add linearly — until saturation. This means you would be hyperactivating the master neuron in a manner that could never occur in nature (Ramachandran, 2000a,b). So this master face neuron may scream out loud (so to speak)‘WOW—what a face! and excite the limbic system correspondingly. Now the advantage with this explanation is that it can be tested experimentally.Finally, the peak shift principle may also help to explain the relationship between a particular artist and her influences. RH write:

Neuroscientists at Oxford and Princeton are currently recording from both types of cells in these very areas. My prediction is that if you find a regular face cell, it should get excited by regular faces but not any more so by a Picasso face (since only one of the views will excite the cell). But if you go to the master cell, where convergence of many views occurs, then that cell will not only respond to any individual view but even better to two views presented simultaneously as in a cubist portrait!

Often paintings contain homages to earlier artists and this concept of homage fits what we have said about caricature: the later artist makes a caricature of his acknowledged predecessor, but a loving one, rather than the ridiculing practised by the editorial cartoonist. Perhaps some movements in the history of art can be understood as driven by a logic of peak shift: the new art form finds and amplifies the essence of a previous one (sometimes many years previous, in the case of Picasso and African art).Grouping

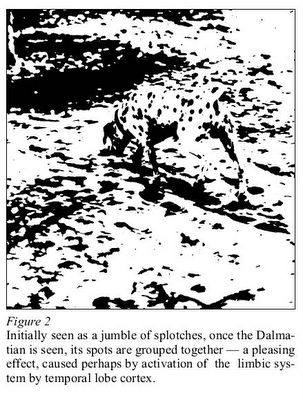

The early parts of our visual system are designed, in large part, to detect signals in a world of noise. RH argue that discovering correlated features in the visual field, and binding those features, must be rewarding, in order to ensure that we continue to do so despite the difficult. The rewarding nature of this is illustrated in the "AHA" sensation that we often get when we discover a figure among a noisy background. After discovering this figure, we are unable not to notice it again (think of the man, or rabbit, in the moon). To illustrate this, RH provide two figures, which I've given below. In the first, random splotches turn into a face as we bind the features together. In the second, the same processes discover a dalmation. They argue that the discovery of such groupings on different perceptual dimensions (they list space, colour, depth, and motion) are individually reinforcing because it is adaptive to keep such discoveries from individual perceptual modules in memory for later processing. Thus, the presence of groupings on various perceptual dimensions in art should produce an aesthetically pleasing experience.

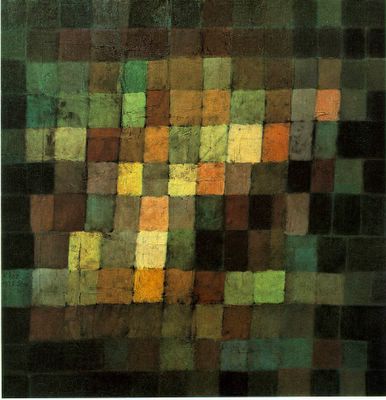

For examples of this principle from art, consider the following painting by Paul Klee:

Paul Klee, "Ancient Sound, Abstract on Black"

It is impossible not to see the bright squares as a group in contrast to the darker squares that form its background. According to RH, this grouping on the brightness dimension should cause the relevant module in the visual system to send a signal straight to the limbic system, which then causes a pleasant sensation, producing the aesthetic experience that we get from the painting.

Contrast

The Klee painting also helps to illustrate another of Ramachandran's principles, contrast. RH write:

Cells in the retina, lateral geniculate body (a relay station in the brain) and in the visual cortex respond mainly to edges (step changes in luminance) but not to homogeneous surface colours; so a line drawing or cartoon stimulates these cells as effectively as a ‘half tone’ photograph. What is frequently overlooked though is that such contrast extractions — as with grouping — may be intrinsically pleasing to the eye (hence the efficacy of line drawings). Again, though, if contrast is extracted autonomously by cells in the very earliest stages of processing, why should the process be rewarding in itself? We suggest that the answer... has to do with the allocation of attention. Information (in the Shannon sense) exists mainly in regions of change—e.g. edges—and it makes sense that such regions would, therefore, be more attention grabbing — more ‘interesting’ — than homogeneous areas. So it may not be coincidental that what the cells find interesting is also what the organism as a whole finds interesting and perhaps in some circumstances ‘interesting’ translates into ‘pleasing’.In the Klee painting, the contrasts make the painting. In this case, the groupings that are pleasing are created by the perception of edges between squares of different levels of brightness (for more examples, see these two paintings). Brightness need not be the only dimension on which we find contrast pleasing, however. Color, for instance, is often used to form striking contrasts (see, for example, these two paintings by Matisse).

While these examples, and the primary motivation for this principle, come from our knowledge of the early visual system, RH also give one example of the use of contrast that may utilize higher-order visual processes. They write:

A nude wearing baroque (antique) gold jewellery (and nothing else) is aesthetically much more pleasing than a completely nude woman or one wearing both jewellery and clothes, presumably because the homogeneity and smoothness of the naked skin contrasts sharply with the ornateness and rich texture of the jewellery.They admit that this example may bear only a figurative resemblance to contrasts on early visual dimensions like color and brightness, but the use of such examples may lead to interesting predictions about the use of higher-order contrasts in art, and their role in the aesthetic experience. If these higher-order contrasts turn out to be aesthetically pleasing for reasons similar to those of the lower-order contrasts, then we may find that contrast itself is one of the most pervasive principles in art.

That's probably enough for one post. In the next post, I'll discuss the remaining principles. Feel free to comment on these before I get to the rest.

UPDATE: The third post in the series is here.

1 Hanson, H. M. (1959). Effects of discrimination training on stimulus generalization. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 321-334.

2 Thornhill, R., & Gangestad, S. W. (1999). Facial attractiveness. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 3(12), 452-460.

Carnival of the Godless and Carnival Ideas

The post you send in must be from a godless perspective and address something such as atheism, church/state separation, the evolution/creation debate, theodicy, philosophy of religion, etc. There is a huge amount of wiggle room in the post subject and we will consider every submission carefully for inclusion.That makes this Carnival sound somewhat interesting, but the following makes it potentially very interesting:

"From a godless perspective" does NOT mean that you must be an atheist to send in a submission. There are plenty of theists who blog from a godless perspective. We welcome their posts. We will even consider posts criticizing godlessness in general, or atheism in particular. We recognize that there are some damned interesting theists out there who will have written relevant posts.The possibility of a wide variety of perspectives could make for very interesting reading.

On an only partially related note, I personally think it would be interesting to have topical "carnivals" that are sort of like special sessions at scholarly conferences. There are a couple ways this could be done. The first is to just propose a topic, and then have people write and submit posts on it. The topics would be more specific than those that most of the carnivals elicit. The second way to do it would be to take a post (either one that's already written, or one that someone is invited to write), and ask for submissions that comment on that post. After all the submissions are in, the author of the original post could then write a reply to them. I don't know if either of these ideas is really feasible, but it's something to think about.

The Cognitive Science of Art: Goals and Motivations of Neuroaesthetics

The best place to start when describing the goals of a research program is with the statements of the researchers themselves. V.S. Ramachndran, whose work on art and neuroscience has sparked a great deal of interest and controversy, put it this way1:

If a Martian ethologist were to land on earth and watch us humans, he would be puzzled by many aspects of human nature, but surely art—our propensity to create and enjoy paintings and sculpture—would be among the most puzzling. What biological function could this mysterious behaviour possible serve? Cultural factors undoubtedly influence what kind of art a person enjoys — be it a Rembrandt, a Monet, a Rodin, a Picasso, a Chola bronze, a Moghul miniature, or a Ming Dynasty vase. But, even if beauty is largely in the eye of the beholder, might there be some sort of universal rule or ‘deep structure’, underlying all artistic experience? The details may vary from culture to culture and may be influenced by the way one is raised, but it doesn’t follow that there is no genetically specified mechanism — a common denominator underlying all types of art. (p. 16)The search for universals in art is by no means a new one, but Ramachandran and others (most notably Semi Zeki) have resolved to do so by understanding the neurological mechanisms that all (or most) art utilizes. Zeki writes2:

What is art? What constitutes great art? Why do we value art so much and why has it been such a conspicuous feature of all human societies? These questions have been discussed at length though without satisfactory resolution. This is not surprising. Such discussions are usually held without reference to the brain, through which all art is conceived, executed and appreciated. Art has a biological basis. It is a human activity and, like all human activities, including morality, law and religion, depends upon, and obeys, the laws of the brain. (p. 53)If art, both in its creation and appreciation, is a product of brains, then it stands to reason that we may gain valuable insight into the nature of art by understanding how it acts on our brains. Specifically, we may be able to utilize our knowledge of the workings of the visual system, and its connections to emotional centers of the brain, to understand why certain themes, forms, and schemes can be found in art across cultures, and why some works of art are more aesthetically pleasing than others. In order to do this, Ramachandran, Zeki, and others have developed several hypotheses designed to produce testable predictions (often counterintuitive) about the role of the visual system in the production and appreciation of art.

This project differs, markedly, from traditional approaches to art, in which art is treated as amorphous, or ineffable; a product of irreducible subjective and cultural phenomena. Thus traditional aesthetic theories are untestable by their very nature. The hope of neuroscientists is not that art will be completely explainable from neurological principles alone. On the contrary, these neurological principles are meant to be foundations onto which the more subjective and culturally relative aspects of art are built. Even if the insights that we can gain from neuroscience constitute only a fraction of what art is (Ramachandran often uses 10% as a figure for the portion of art that he is attempting to explain0, then we will have accomplished something. We may then be better able to understand the development and utilization of subjective and cultural standards in art.

For example, if there are universals in art that are products of our neural composition, then this approach may allow us to solve some of the problems that philosophers and aesthetic theorists have puzzled over for centuries. Consider the problem of beauty typified in Kant's antinomy of the non-conceptual aspect of aesthetic judgement and the conceptual nature of taste. With reference to the work of Ramachandran and his colleagues, Jennifer McMahon writes3:

[Ramachandran & Hirstein's principles] would represent or explain the relation between certain properties of the beautiful object and the viewer’s pleasure, in such a way that would ground judgments of beauty and also explain why beauty is ineffable. After all, it is the way perceptual principles are employed in the course of perceiving the beautiful object that causes the pleasure. We cannot subsume these principles under a concept as we can the incoming data which give rise to logical condition-governed concepts, because these principles are a part of the architecture of the mind; hence, beauty’s ineffability. (p. 31)If nothing else, a scientific approach to aesthetics should spark debate, about the essence of art, beauty, and human nature. Hopefully, the prospects of such a project are enough to whet some of your appetites. In the next post, I'll discuss at length (probably too much length) Ramachandran's 8 (sometimes 10) universal principles of art. After that, I'll get into the issue of beauty more specifically, and finally, I may talk a little about non-visual art, and literary arts in particular.

1 Ramachandran, V.S., & Hirstein, W. (1999). The science of art: A neurological theory of aesthetic experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 1, 15-35.

2 Zeki, S. (2002). Neural concept formation and art: Dante, Michelangelo, Wagner. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 9, 53-76.

3 McMahon, J.A. (2000). Perceptual principles as the basis for genuine judgements of beauty. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(8-9), 29-35.

UPDATE: The next post is here.

Wednesday, January 19, 2005

Invincible Summers

First, what did Summers say? He made two different points:

- One of the reasons that there is a dearth of female professors in the sciences may be genetic differences between males and females.

- With reference to the small number of female professors in the sciences, he stated, ''Research in behavioral genetics is showing that things people previously attributed to socialization weren't."

On his first point, is it a viable hypothesis? I was arguing in the first post that it's not, and despite Summers' assertions, we do have plenty of research to assess it. As I said in my first post, the research shows that there are no differences in primary math skills (counting, arithmetic, subitizing, ordinality, numerosity, etc.) across cultures, and these abilities appear to have very little genetic influence. There are, however, consistent differences in secondary math abilities across cultures in the general population, though when more specific populations are tested, the differences vary greatly. Furthermore, there is ample evidence that these differences are largely (though not entirely) due to sociological factors*.

- The emergence of secondary math skills is largely dependent on cultural institutions.

- The role of discrimination in primary and secondary schools in both math confidence and motivation in females (some of which Clark mentioned in comments to my last post, and Dr. Myers' mentioned in his post), including the evidence presented in the Sherman studies (see footnote 1), as well as the Casey et al. (1997) and the stereotype-threat studies cited in my last post.

- Another piece of evidence is the actual differences in performance in males and females on the SAT-M (the primary test used to measure sex differences in math). These differences are largely in the number of correct answers. When the ratio of correct answers are compared, there are no differences (at least in college-bound and college-attending females). Thus, the consistent differences appear to be due to males answering more questions, a result which may indicate that females are slower in mathematical reasoning, but not worse overall (an interpretation that the results from non-speeded mental rotation tests also suggest).

- The fact that the effect sizes (which, in the early seventies, were a whopping .3) for the differences between males and females on the SAT-M and similar tests have dropped significantly over the last 30 years (from about .3 to around .14). See Hyde et al. from the previous post.

Number 4 also serves as the best reply to Summers' second point. While there have been arguments for decades that biological, rather than sociological factors are responsible for the small percentage of women in science and math careers, making Summers' statement seem a bit odd, there has also been ample evidence over this time that sociological factors do play a large role (see, for more examples, any of the Eccles publications that you can request from this site). The best illustration of this, to my mind, is effect size. It is extremely unlikely that the small effect sizes in math ability could explain the huge effect sizes in career entrance and success. Even if we look at only the highest scoring males and females, the differences in number are too small to account for the large differences in a wide variety of math-intensive fields, both within and outside of academia.

* See e.g., Sherman, J. (1980) Mathematics, spatial visualization, and related factors: Changes in girls and boys, grades 8-11. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72, 476-82. Sherman, J. (1981) Girls' and boys' enrollments in theoretical math courses: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Woman Quarterly, 5, 681-89.

Tuesday, January 18, 2005

Implicit Prejudice, the IAT, and the Popular Press

At this point, it is undeniable that much of our behavior is either determined or heavily influenced by factors that are below the level of our awareness or that we are not able to consciously control. There are many examples of this in the literature. For example, our arousal level, which in most contexts is beyond our control (unless we're master yogis), can influence our perceptions of the attractiveness of others. Thus, studies have shown that we will rate people as being more attractive if we view their photos (or encounter them in person) immediately after a strenuous exercise session, or while we are standing near the edge of a high ledge. In these situations, our arousal levels are high, and we can mistakenly attribute the increased level of arousal to a person rather than their actual causes.

Another example of the unconscious influences on our behavior is the way our current goals affect our perceptions of value. The effect of current goals on intertemporal choice is well documented, but they can also influence current choices in ways of which we are not always aware. Imagine that we are shopping for cars, and after viewing a first car, we become hungry (though we don't consciously notice this) just before viewing a second car. If we do not satisfy this goal before viewing the second car, we will perceive it as less valuable than we otherwise would. Thus, even if the first and second car would ordinarily be viewed as equally valuable, viewing the second car while we have a strong goal that is not related to car-buying (in this case, hunger) will tend to cause us to perceive it as less valuable than the first car. This is because goal-irrelevant objects tend to be "devalued" relative to their default value.

As these and many other examples show, unconscious influences on our behavior are pervasive. Recently, however, researchers have begun to research "unconscious attitudes," and in particular "unconscious prejudices." Several methods for testing for these implicit attitudes have been developed, including implicit priming, the implicit association test (and its more recent incarnation, the Go/No-Go Association Test), and the evaluative movement assessment. The impetus for these tests was the recognition that explicit tests of unsavory attitudes and prejudices would be overly influenced by demand characteristics. Implicit tests, it was thought, would tap into these attitudes in ways that would not be influenced by conscious beliefs about things like the popularity of the attitudes. And originally, there was good reason to think that the IAT, the most popular of these tests, was doing just this. IAT performance is not completely dependent on intention, and because IAT results (in the form of rank-order preferences) don't correlate well with explicit measures, there's good reason to believe that they are showing us things that explicit measures couldn't.

It's very "sexy" (to use the social psychologists' own buzz-word) to talk about unconscious prejudices and implicit attitudes, and for this reason, it doesn't surprise me that IAT results showing that white participants seem to harbor unconscious prejudices towards African Americans, or other out-groups, are now receiving attention in the popular press. As a quote from the above-linked book demonstrates, these results are striking:

One of the reasons that IAT has become so popular in recent years as a research tool is that the effects it is measuring are not subtle…the IAT is the kind of tool that hits you over the head with its conclusions. “When there’s a strong prior association, people answer in between four hundred and six hundred milliseconds,” says [psychologist Anthony G.] Greenwald. “When there isn’t, they might take two hundred to three hundred milliseconds longer than that – which is in the realm of these kinds of effects is huge. One of my cognitive psychologist colleagues described this as an effect you can measure with a sundial.” (p.77)Recent work,however, has shown that conclusions of "prejudice" from IAT scores may be unwarranted. First, there appear to be several methodological problems with the IAT (e.g., the evaluations of one category are influenced by those of the opposing category; see the discussion in this paper). In addition, people routinely evaluate nonwords more negatively than words. Can we infer, then, that people have an implicit prejudice against nonwords? In reality, it's likely that things like familiarity and arousal level are influencing IAT results. There are new implicit tests (e.g., the one in the linked paper) that are designed to avoid some of these problems, but even with these tests, inferring "prejudice" or even "attitudes" in general is discouraged. Thus, while it is safe to conclude that unconscious factors influence our perceptions and behavior, it is premature to conclude that we can test for the existence of unconscious prejudices.

Will the popular press take heed of the methodological and theoretical problems with IAT scores? Probably not. While Lakoff's framing analysis has been criticized by many conservatives, neither conservatives nor liberals have paid any attention to the fact that the conceptual metaphor theory upon which it is based has been largely discredited by empirical research. IAT and implicit prejudices are even sexier than framing analysis, and seem to hold appeal for both liberals and conservatives. Hopefully, like most fads, this one will eventually just fade away, at least until the research catches up with the conclusions that have sparked the popular interest in the first place.

Monday, January 17, 2005

Sex Differences and Science Careers

The study of sex differences in cognitive abilities has been muddled, for decades, by political agendas on both sides, but there is a fairly clear picture beneath all the muck, and that clear picture is that there is no clear picture. For a long time, it was believed that the primary area in which robust cognitive differences between males and females existed was in spatial-reasoning1. Spatial reasoning, in turn, was thought to underlie what are sometimes called the "secondary" mathematical abilities, i.e. those that we use for the first time in high school math courses (especially geometry and calculus). Those who held these view were not surprised, then, when sex differences in secondary mathematical abilities were discovered. For instance, Casey et al.2 found that for "high-ability groups" (i.e. those who might someday want to make mathematics or math-intensive sciences their careers), superior performance on mental rotation tasks by males explained the bulk of the difference in performance on the math section of the SAT ("high ability" males perform better on the SAT-M than "high ability" females).

The view that there are differences between mathematical abilities in males and females, and that these abilities are due, in large part, to differences in spatial reasoning abilities (to the exclusion of social and affective explanations) is still prominent, and might even be called the received view3. To be fair, there is empirical support for this view (e.g., the Casey et al. study, and those listed in footnote 3). Yet, for decades, there has also been a substantial amount of research demonstrating a.) that spatial differences don't explain differences in math performance and b.) differences in both spatial and mathematical abilities vary greatly depending on the context and population studied. For example, Goldstein et al.4 demonstrated that the performance of females and males on a mental rotation task only differed in a timed version of the task, indicating that the speeded mental rotation task may not be testing absolute spatial ability, but the speed with which people are able to reason about spatial ability. Further, an extensive review of the literature from a 4 decade period showed no significant correlation between spatial and mathematical abilities, but did find a significant correlation between verbal and mathematical abilities5. This review also found that female college students performed better on math tests than males. Another problem is that there appears to be a high degree of intra-individual variability in performance on both math and spatial reasoning tests. Some have even found that females' performance differs depending on their hormone levels, and thus their menstrual cycle6.

This is by no means an exhaustive review of the literature. Such a review would have to be of book length. Still, this is enough to make my point: while it does appear that there may be some specific sex differences in both spatial and mathematical reasoning, exactly what these differences are, and what causes them, is still very unclear. There is, however, one thing about gender differences in acheivement in mathematics and math-intensive sciences that is undeniable: gender discrimination exists, and it does play a significant role. As research on stereotype-threat theory has shown, the existence and consciousness of stereotypes can significantly affect people's performance on stereotype-relevant tasks7. Specifically, female performance on math tests has been shown to be negatively affected by gender stereotypes8.Furthermore, these stereotypes will, consciously or unconsciously, affect the evaluation of female students and job/tenure candidates, a fact that research on implicit attitudes has demonstrated quite well.

This brings us to the real reason why Summers deserves the harsh criticism. He is probably right that there exist real sex differences, across the entire population, in math abilities, but we know too little about the sources of these differences to be speaking definitively about them in public forums. Furthermore, what he is horribly wrong about is the role of discrimination and stereotypes in the success of women in math and science careers, or even on their performance on math and science tests. As Andrew of Universal Acid aptly notes, the existence of innate differences does not necessarily explain all of the differences in acheivement, and since research has shown that stereoptypes and discrimination are responsible for some acheivement differences, Summers' attempt to discount these as factors can only serve to perpetuate those differences. The effects of stereotypes are mediated, in part, by the authority of their purveyors, and when someone in Summers' position reiterates pernicious stereotypes, their negative effects can only increase.

1 See Vandenberg, S. G. & Kuse, A. R. (1978) Mental rotations, a group test of three-dimensional spatial visualization. Perceptual and Motor Skills 47: 599-604, for an old review of the mental rotation literature, on which most of the sex difference theories were and continue to be based.

2 Casey, M.B., Nuttall, R., Pezaris, E., and Benbow, C.P. (1995). The influence of spatial ability on gender differences in mathematics college entrance test scores across diverse samples. Developmental Psychology, 31, 697-705.

3 See e.g., Casey M.B. (1996). Understanding individual differences in spatial ability within females: A nature/nurture interactionist framework. Developmental Review, 16(3), 241-260; Geary, D.C., Saults, S.J., Liu, F., & Hoard, M.K. (2000). Sex differences in spatial cognition, computational fluency, and arithmetical reasoning. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 77, 337–353; Hyde, J.S., Fennema, E., & Lamon, S.J. (1990). Gender differences in mathematics performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 2, 139-155; and Casey, M.B., Nuttall, R.L., Pezaris, E. (1997). Mediators of gender differences in mathematics college entrance test scores: a comparison of spatial skills with internalized beliefs and anxieties. Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 669-680.

4 Goldstein, D., Haldane, D., & Mitchell, C. (1990). Sex differences in visual-spatial ability: the role of performance factors. Memory and Cognition, 18(5), 546-550.

5 Friedman, L. (1995). The space factor in mathematics: Gender differences. Review of Educational Research, 65(1),22-50.

6 Silverman, I. & Phillips, K. (1993) Effects of estrogen changes during the menstrual cycle on spatial performance. Ethology and Sociobiology, 14, 257-270.

7 Steele, C. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52, 613–629.

8 Osborne, J.W. (2001). Testing stereotype threat: Does anxiety explain race and sex differences in achievement? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 26, 291-310.

Sunday, January 16, 2005

Martin Luther King's Birthday

Your Majesty, Your Royal Highness, Mr. President, excellencies, ladies and gentlemen: I accept the Nobel Prize for Peace at a moment when twenty-two million Negroes of the United States of America are engaged in a creative battle to end the long night of racial injustice. I accept this award in behalf of a civil rights movement which is moving with determination and a majestic scorn for risk and danger to establish a reign of freedom and a rule of justice.

I am mindful that only yesterday in Birmingham, Alabama, our children, crying out for brotherhood, were answered with fire hoses, snarling dogs and even death. I am mindful that only yesterday in Philadelphia, Mississippi, young people seeing to secure the right to vote were brutalized and murdered. And only yesterday more than 40 houses of worship in the State of Mississippi alone were bombed or burned because they offered a sunctuary to those who would not accept segregation.

I am mindful that debilitating and grinding poverty afflicts my people and chains them to the lowest rung of the economic ladder.

Therefore, I must ask why this prize is awarded to a movement which is beleaguered and committed to unrelenting struggle; to a movement which has not won the very peace and brotherhood which is the essence of the Nobel Prize.

After contemplation, I conclude that this award which I receive on behalf of that movement is profound recognition that nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral question of our time -- the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to violence and oppression.

Civilization and violence are antithetical concepts. Negroes of the United States, following the people of India, have demonstrated that nonviolence is not sterile passivity, but a powerful moral force which makes for social transformation. Sooner or later all the people of the world will have to discover a way to live together in peace, and thereby transform this pending cosmic elegy into a creative psalm of brotherhood.

If this is to be achieved, man must evolve for all human conflict a method which rejects revenge, aggression and retaliation. The foundation of such a method is love. The tortuous road which has led from Montgomery, Alabama, to Oslo bears witness to this truth. This is a road over which millions of Negroes are travelling to find a new sense of dignity.

This same road has opened for all Americans a new ear of progress and hope. It has led to a new Civil Rights bill, and it will, I am convinced, be widened and lengthened into a superhighway of justice as Negro and white men in increasing numbers create alliances to overcome their common problems.

I accept this award today with an abiding faith in America and an audacious faith in the future of mankind. I refuse to accept despair as the final response to the ambiguities of history. I refuse to accept the idea that the "isness" of man's present nature makes him morally incapable of reaching up for the eternal "oughtness" that forever confronts him.

I refuse to accept the idea that man is mere flotsom and jetsom in the river of life unable to influence the unfolding events which surround him. I refuse to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality.

I refuse to accept the cynical notion that nation after nation must spiral down a militaristic stairway into the hell of thermonuclear destruction. I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant.

I believe that even amid today's motor bursts and whining bullets, there is still hope for a brighter tomorrow. I believe that wounded justice, lying prostrate on the blood-flowing streets of our nations, can be lifted from this dust of shame to reign supreme among the children of men.

I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality and freedom for their spirits. I believe that what self-centered men have torn down, men other-centered can build up. I still believe that one day mankind will bow before the altars of God and be crowned triumphant over war and bloodshed, and nonviolent redemptive goodwill will proclaim the rule of the land.

"And the lion and the lamb shall lie down together and every man shall sit under his own vine and fig tree and none shall be afraid."

I still believe that we shall overcome.

This faith can give us courage to face the uncertainties of the future. It will give our tired feet new strength as we continue our forward stride toward the city of freedom. When our days become dreary with low-hovering clouds and our nights become darker than a thousand midnights, we will know that we are living in the creative turmoil of a genuine civilization struggling to be born.

Today I come to Oslo as a trustee, inspired and with renewed dedication to humanity. I accept this prize on behalf of all men who love peace and brotherhood. I say I come as a trustee, for in the depths of my heart I am aware that this prize is much more than an honor to me personally.

Every time I take a flight I am always mindful of the man people who make a successful journey possible -- the known pilots and the unknown ground crew.

So you honor the dedicated pilots of our struggle who have sat at the controls as the freedom movement soared into orbit. You honor, once again, Chief (Albert) Luthuli of South Africa, whose struggles with and for his people, are still met with the most brutal expression of man's inhumanity to man.

You honor the ground crew without whose labor and sacrifices the jet flights to freedom could never have left the earth.

Most of these people will never make the headlines and their names will not appear in Who's Who. Yet when years have rolled past and when the blazing light of truth is focused on this marvelous age in which we live -- men and women will know and children will be taught that we have a finer land, a better people, a more noble civilization -- because these humble children of God were willing to suffer for righteousness' sake.

I think Alfred Nobel would know what I mean when I say that I accept this award in the spirit of a curator of some precious heirloom which he holds in trust for its true owners -- all those to whom beauty is truth and truth beauty -- and in whose eyes the beauty of genuine brotherhood and peace is more precious than diamonds or silver or gold.

Philosophers' Carnival VIII

UPDATE: Finally I have had time to read my way through the entire Carnival. As usual, Brandon has a solid entry, in this case a nice post on approaches to Hume on the external world, while Melbourne Philosopher has an interesting post on First Causes.