From Aristotle through speech act theories, metaphor had been viewed as a secondary type of language, built on literal speech which is, in turn, the true nature of language. However, since the 1970s, cognitive scientists have become increasingly convinced that metaphor is not only central to thought, something that Aristotle would admit, but that it is also a central aspect of language, and no less priveleged than literal language. Metaphors are processed as quickly as literal language, and as automatically. In addition, metaphors, while generally literally false, are difficult to label as literally false. This new status for metaphor has led to a great deal of attention among cognitive scientists, and a wealth of theories and models of metaphor. It would be prohibitively time-consuming (and unthinkably pointless) to detail each of these models along with the evidence for them, so instead I will focus on two models, the structure mapping model of Gentner and colleagues, and the attributive categorization model of Glucksberg and Keysar. These models are the most prominent, and the most empirically viable. Furthermore, they capture two diametrically opposed (at least ostensibly) ways of viewing metaphor. Also, I refuse to talk about Lakoff and cognitive linguistics until after the election, which means that cognitive linguistics theories of metaphor are off the table. Before I get to the current theories, though, I'll give a very brief history of cognitive views of metaphors.

Originally, almost all theories of metaphor were two-process theories, which involved metaphorical statements first being processed as literal statements, and when it was discovered that the statements did not work as literal statements, they were then, and only then, processed as metaphors. This view was already on its way out in 1982 when a classic experiment by Glucksberg et al. 1 made it completely untenable. In their experiment, participants read three types of class-inclusion statements. The statements were either literally true ("Some birds are robins"), literally false and "anomolous" (i.e., they couldn't easily be interpreted metaphorically, as in "Some birds are apples"), or metaphorical ("Some lawyers are sharks"). Participants were asked to judge whether the statements were literally true, and their reaction time in making this judgement was measured. Participants were quick to judge literally true statements as true, and literally false and anomolous statements as false, but they were significantly slower when rating metaphorical statements as literally false. This was interpreted to mean that the participants were automatically interpreting the metaphorical statements metaphorically, and a subsequent literal interpetation required more time. This rules out the view that the statements must be interpreted literally first, prior to any metaphorical interpretation. If this were in fact the case, then participants should have noticed that they were literally false in about the same time that they noticed the falsity of the anomolous statements.

Cognitive scientific views of metaphor that do not treat them as less priveleged than literal statements began to surface in the 1970s, andsince then almost all of them have arisen out of the work of Max Black. Black2 discussed several different cognitive theories of metaphor, the most prominent of which were the substitution, simile, and interactive theories. In the substitution theory of metaphor, the cognitive processing of metaphor involved substituting a property of the vehicle for the vehicle itself. So, "My surgeon is a butcher" becomes "My surgeon is sloppy," or "My lawyer is a shark" becomes "My lawyer is aggressive." The simile theory is similar, in that it views metaphors as highlighting properties of the vehicle that can be attributed to the topic. However, under this view, metaphors are essentially substituted with a corresponding simile (shades of Aristotle). "My surgeon is a butcher" becomes "my surgeon is like a butcher," and the comparison highlights the pragmatically relevant common attributes. Finally, the interactive theory of metaphor again involves a comparison between the vehicle and topic, but in this case, the properties that are highlighted by the comparison are determined by the interaction of the topic and vehicle.

In general, the interactive theory of metaphor has been the most influential of Black's various theories, and is ultimately the one that he himself accepts. However, it does suffer from a glaring problem: it's extremely abstract. I wish I could tell you that it was more detailed than my short description in the preceding paragraph, but it's really not. How do the topic and vehicle interact? How are the relevant properties selected? These questions would need to be answered before we could claim that the interactive account of metaphor is sufficient as a cognitive theory. To rectify these defects, several theories based on the interactive theory have been proposed over the last few decades. The first of these, called the salience imbalance theory3, solves the problem of feature selection by positing that metaphors involve comparisons between topics and vehicles that exhibit an imbalance in the saliency of the properties the creator of the metaphor wishes to hilghight. For instance, sharks exemplify aggression in a much more salient way than lawyers, and by making the comparison in the metaphor "My lawyer is a shark," the salience of the "aggressive" feature in sharks serves to highlight this feature in my lawyer. One of the primary motivations for this theory is the assymetry in metaphorical comparisons. "My lawyer is a shark" is a much more acceptable, and powerful statement (in most contexts) than, "The shark is a lawyer." This theory, and many subsequent theories, have been motivated by a desire to explain this inherent assymetry in all metaphors.

The salience imbalance theory, while it is an improvement on the interactive theory, still suffers from many problems. It doesn't detail how the comparison takes place, and its explanation of how properties are highlighted is still somewhat abstract. After the salience imbalance approach, theories of metaphor split into three different types, all still roughly based on Black's work, but with different solutions to the problems of Black's and Ortony's theories. The first type treats metaphor as an instance of analogy, or more accurately, as using the same processes as analogy. Under this view, called structure mapping, metaphor involves mappings between the topic and vehicle. Thus, it is also a comparison view of analogy, but one with a much more sophisticated comparison process than either the interactive or salience imbalance theories. The second type treats metaphors as categorization statements. Specifically, under the attributive categoriztion theory, metaphors are treated as class-inclusion statements, which involve placing the topic into a category defined by a feature or features exemplified by the vehicle. For example, "My lawyer is a shark" involves placing "My lawyer" in the category of "aggressive things" of which "shark" is a highly salient or typical member. The final widely used type of cognitive theory of metaphor comes out of cognitive linguistics, and is either based on Lakoff's conceptual metaphor theory, or blending. However, talking about this will have to wait until after the election, because I don't want to type type name "Lakoff" again until then.

In the next post, I'll describe the structure mapping view of metaphors in more detail. This theory is very interesting because it comes up with a way to classify different types of metaphors based on the sorts of arguments that are mapped between the topic and vehicle. After that, I'll discuss the attributive categorization model in a third post. After that, who knows what will happen?

1 Glucksberg, S ., Gildea, P., & Bookin, H. (1982) . On understanding non-literal speech : Can people ignore metaphors? Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 1, 85-96.

2 Black, M. (1955). Metaphor. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 55, 273-294, Black, M. (1962). Models and Metaphors. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, and Black, M. (1979). More about metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought (pp. 19-43). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

3 Ortony, A. (1979). Beyond literal similarity. Psychological Review, 86, 161-180, and Ortony, A. (1993). The role of similarity in similes and metaphors. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought 2nd Ed., (pp. 342-356). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

An entrée of Cognitive Science with an occasional side of whatever the hell else I want to talk about.

Sunday, October 31, 2004

Saturday, October 30, 2004

The First (Sort Of) Request: Memory and Epistemology

In a comment, Clark Goble writes:

Now I'm no expert in epistemology, and I don't read a lot of the contemporary epistemology literature (I find it kind of boring, to be honest), but as I'm the foremost authority on epistemology among the authors of this blog, I will take it upon myself to post on it anyway. I do know of a few discussions of memory in the context of epistemology. One is online, here. It takes an internalist position, but there is a lengthy discussion of both externalist and internalist solutions to the fallibility of memory. Audi has a chapter on memory in his Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge, and I think a few other epistemology textbooks have chapters on memory as well.

Otherwise, memory has been a hot topic in philosophy for a long time. Aristotle discussed it, as did Hume (Section III here and Section IV and V here) and the other British empiricists. In the 20th century, Russell talked about memory often, including some great passages in The Analysis of Mind; the logical positivists talked about it fairly frequently (Ayer has a lengthy discussion of memory, and statements about the past in particular, in The Problem of Knowledge); and C. I. Lewis has an excellent chapter in An Analysis of Knowledge and Valuation in which he argues that the fallibility of memory demands a coherentist account of knowledge. Here is what writes about the implications of the potential for memory errors:

Of course, phenomenologists talk about memory a lot, as well. I'm sure Clark knows of Bergson's Matter and Memory, and (inspired by Bergson) Merleau-Ponty spends a lot of time talking about memory (as does Deleuze, at least when talking about Bergson). There was also a special issue of Philosophy and Phenomenological Research in the early 80s (82 or 83) that contained several excellent papers on memory. One of the papers in that issue is a brief review of the philosophy of memory over the last few millenia.

The philosopher who probably paid more attention to memory than any other in the last half century was Norman Malcolm. Much of his work on memory (e.g., in Memory and Mind ) involves a Wittgensteinian critique of representationalist, or trace theories of memory. In particular, he argues that the existence of "enduring representations" doesn't fit with our experience of direct access to memory, and creates the need for homunculi. He also talks about "false memories," though he doesn't call them that, and argues that memory is like knowledge, and therefore can't be mistaken. Any case that we might call "false memory" doesn't involve memory at all, or if it does, it involves a correct memory of a past impression which is what was actually mistaken. Here's an example Malcolm gives in "Memory and the Past" (which was in The Monist in 1963, vol 47):

I disagree with Malcolm's anti-trace arguments, in part because I think that the reconstructionist view of memory which is popular in cognitive psychology now does away with the problems he discusses. Under the reconstructionist view, which I share, memories do involve enduring representations, but remembering involves reconstructing those representations on-line, and this reconstruction is influenced by the structure of the representation as well as the context in which the remembering takes place. In this case, no homunculus is needed, as the present context is doing the work that the homunculus would have to do in older representationalist theories.

On the subject of false memories, Malcolm makes an interesting point, though what research shows is actually happening is that the memory mistakes the context of the original impression. The original impression is often not mistaken, however. For instance, during a therapy session involving suggestive visualization techniques, the visualizations may or may not be interpreted as products of the imagination or as memories of past events, but later memories of those visualizations may mistakenly involve the belief that they are memories of actual events, rather than a visualization exercise.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Moving on, I do think Clark is correct that the reconstructive nature of memory, as well as its fallibility, can pose problems for theories of knowledge which require that we have evidence to justify a belief. In most cases, that evidence will not be present at the time that we have a belief, except in the form of memories. I think epistemologists recognize this, though I'm not sure they're aware of much of the memory research of the last 30 years. For instance, research on the remember-know distinction (and similar distinctions, e.g., remember, know, and feel) has shown that people have qualitatively different types of memory experiences, and these types relate to accuracy -- when people feel they know something happened in the past, they tend to be correct more often than if they remember or feel it happened in the past. Also, research on the effect of background knowledge on memories for particular events has shown over and over again that background knowledge tends to intrude on memories of related events, causing us to falsely remember as being part of the event information in background knowledge that was not in fact present in the event. I suspect that these sorts of findings have implications for epistemological issues, but I'm not exactly sure what those implications are.

Here's another interesting finding from memory research that might have epistemological implications. In a classic experiment, Pichert and Anderson1 asked participants to read a story in which a house was described. The participants were told to read the story from one of two perspectives, either a potential home buyer or a burglar. After a delay, participants were asked to recall as much as they could about the story. During this first recall session, participants recalled significantly more information about the house that was relevant to their perspective (e.g., the potential home buyer might remember defects in the house, and burglars might remember information about the entrances and exits) than information that was relevant to the other perspective, but not theirs. After the first recall session, participants were told to think about the story again, but this time, from the other perspective (potential home buyers were now told to be burglars, and vice versa). Then, without reading the story again, they were told to recall as much as they could about the story again. During this second recall, participants were able to recall information about the house that was relevant to their new perspective, but which they had not recalled before. This result shows two things: 1.) The information that was irrelevant to their original perspective (schema) was encoded and 2.) This information was not accessible unless a relevant perspective (schema) was activated.

Now back to epistemology. Imagine a person has a belief, P, and has encoded the information, S, that would justify this belief, but because she has not activated the schema that would allow her to access S, she is not aware of this information. If asked to justify P, she could not access S, and therefore would not be able to do so. Does her belief constitute knowledge, even though she is (consciously) unaware of its justification residing in her memory? If it doesn't constitute knowledge, would it suddenly do so if she were to activate the relevant schema/perspective, and gain access to S?

There you have it, my response to my first request. If that wasn't rambling enough to dissuade anyone from ever asking me about epistemology again, I don't know what would be.

1 Pichert, J. W., & Anderson, R. C. (1977). Taking different perspectives on a story. Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 309-315.

I've always wondered about the role of memory in epistemology. It seems that whenever we talk about rational reasons they are always dependent upon our memory. Even in a math equation, we assume we recall the early steps correctly. Memory is what allows us to transcend the temporal limits of reasoning. Yet, so far as I'm aware, it never gets brought up in epistemological articles. (Or at least I've missed most of them) The role of false memories seems to render a lot of epistemology quite problematic and at a minimum suggests that knowing we know doesn't follow naturally from knowing. While I may be completely wrong, I have this gut feeling that it ought to lead one to externalist accounts as well.

Now I'm no expert in epistemology, and I don't read a lot of the contemporary epistemology literature (I find it kind of boring, to be honest), but as I'm the foremost authority on epistemology among the authors of this blog, I will take it upon myself to post on it anyway. I do know of a few discussions of memory in the context of epistemology. One is online, here. It takes an internalist position, but there is a lengthy discussion of both externalist and internalist solutions to the fallibility of memory. Audi has a chapter on memory in his Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge, and I think a few other epistemology textbooks have chapters on memory as well.

Otherwise, memory has been a hot topic in philosophy for a long time. Aristotle discussed it, as did Hume (Section III here and Section IV and V here) and the other British empiricists. In the 20th century, Russell talked about memory often, including some great passages in The Analysis of Mind; the logical positivists talked about it fairly frequently (Ayer has a lengthy discussion of memory, and statements about the past in particular, in The Problem of Knowledge); and C. I. Lewis has an excellent chapter in An Analysis of Knowledge and Valuation in which he argues that the fallibility of memory demands a coherentist account of knowledge. Here is what writes about the implications of the potential for memory errors:

When the whole range of empirical beliefs is taken into account, all of them more or less dependent on memorial knowledge, we find that those which are most credible can be assured by their mutual support, or as we shall put it, by their congruence.

Of course, phenomenologists talk about memory a lot, as well. I'm sure Clark knows of Bergson's Matter and Memory, and (inspired by Bergson) Merleau-Ponty spends a lot of time talking about memory (as does Deleuze, at least when talking about Bergson). There was also a special issue of Philosophy and Phenomenological Research in the early 80s (82 or 83) that contained several excellent papers on memory. One of the papers in that issue is a brief review of the philosophy of memory over the last few millenia.

The philosopher who probably paid more attention to memory than any other in the last half century was Norman Malcolm. Much of his work on memory (e.g., in Memory and Mind ) involves a Wittgensteinian critique of representationalist, or trace theories of memory. In particular, he argues that the existence of "enduring representations" doesn't fit with our experience of direct access to memory, and creates the need for homunculi. He also talks about "false memories," though he doesn't call them that, and argues that memory is like knowledge, and therefore can't be mistaken. Any case that we might call "false memory" doesn't involve memory at all, or if it does, it involves a correct memory of a past impression which is what was actually mistaken. Here's an example Malcolm gives in "Memory and the Past" (which was in The Monist in 1963, vol 47):

Someone could point at a man in plain sight and say, "I met him last week." The even the refers to is meeting-that-man-last week. His memory is wrong, let us suppose, because he and the man pointed at were in different parts of the world last week. His erroneous memory does not pressupose some correct memory of the event referred to, for it did not take place. Still, his memory might be partly correct, for it might be that he remembered meeting this man but is wrong about when it happened. Or it could be that he had never met this particular man, but had met one who could easily be mistaken for him. Correct memory would here be mixed in with incorrect memory. Another possibility would be that previously he had dreamt of meeting this man, or had hallucinated it, or had formed in some other way an erroneous impression of having met him. But if his present belief was based on a previous false impression, then the present belief would not involve an error of memory: the error would be in the original impression.

I disagree with Malcolm's anti-trace arguments, in part because I think that the reconstructionist view of memory which is popular in cognitive psychology now does away with the problems he discusses. Under the reconstructionist view, which I share, memories do involve enduring representations, but remembering involves reconstructing those representations on-line, and this reconstruction is influenced by the structure of the representation as well as the context in which the remembering takes place. In this case, no homunculus is needed, as the present context is doing the work that the homunculus would have to do in older representationalist theories.

On the subject of false memories, Malcolm makes an interesting point, though what research shows is actually happening is that the memory mistakes the context of the original impression. The original impression is often not mistaken, however. For instance, during a therapy session involving suggestive visualization techniques, the visualizations may or may not be interpreted as products of the imagination or as memories of past events, but later memories of those visualizations may mistakenly involve the belief that they are memories of actual events, rather than a visualization exercise.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Moving on, I do think Clark is correct that the reconstructive nature of memory, as well as its fallibility, can pose problems for theories of knowledge which require that we have evidence to justify a belief. In most cases, that evidence will not be present at the time that we have a belief, except in the form of memories. I think epistemologists recognize this, though I'm not sure they're aware of much of the memory research of the last 30 years. For instance, research on the remember-know distinction (and similar distinctions, e.g., remember, know, and feel) has shown that people have qualitatively different types of memory experiences, and these types relate to accuracy -- when people feel they know something happened in the past, they tend to be correct more often than if they remember or feel it happened in the past. Also, research on the effect of background knowledge on memories for particular events has shown over and over again that background knowledge tends to intrude on memories of related events, causing us to falsely remember as being part of the event information in background knowledge that was not in fact present in the event. I suspect that these sorts of findings have implications for epistemological issues, but I'm not exactly sure what those implications are.

Here's another interesting finding from memory research that might have epistemological implications. In a classic experiment, Pichert and Anderson1 asked participants to read a story in which a house was described. The participants were told to read the story from one of two perspectives, either a potential home buyer or a burglar. After a delay, participants were asked to recall as much as they could about the story. During this first recall session, participants recalled significantly more information about the house that was relevant to their perspective (e.g., the potential home buyer might remember defects in the house, and burglars might remember information about the entrances and exits) than information that was relevant to the other perspective, but not theirs. After the first recall session, participants were told to think about the story again, but this time, from the other perspective (potential home buyers were now told to be burglars, and vice versa). Then, without reading the story again, they were told to recall as much as they could about the story again. During this second recall, participants were able to recall information about the house that was relevant to their new perspective, but which they had not recalled before. This result shows two things: 1.) The information that was irrelevant to their original perspective (schema) was encoded and 2.) This information was not accessible unless a relevant perspective (schema) was activated.

Now back to epistemology. Imagine a person has a belief, P, and has encoded the information, S, that would justify this belief, but because she has not activated the schema that would allow her to access S, she is not aware of this information. If asked to justify P, she could not access S, and therefore would not be able to do so. Does her belief constitute knowledge, even though she is (consciously) unaware of its justification residing in her memory? If it doesn't constitute knowledge, would it suddenly do so if she were to activate the relevant schema/perspective, and gain access to S?

There you have it, my response to my first request. If that wasn't rambling enough to dissuade anyone from ever asking me about epistemology again, I don't know what would be.

1 Pichert, J. W., & Anderson, R. C. (1977). Taking different perspectives on a story. Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 309-315.

Friday, October 29, 2004

Down with Politics, Up with Cognition!

I am so thoroughly annoyed/frustrated/bored/disenchanted with politics at this point, with the election only 4 days away, that I can no longer even read political posts. Voter fraud? I don't want to hear about it. Missing explosives? I won't read about it. A bin Laden video? Seriously, who cares? Not I, that's for sure. So, since I won't be reading about it, I sure as hell won't be posting about it. Instead, I'll post about cognition up until the election. So, if anyone who happens by has any issues in cognitive science, psychology (including cognitive, social, or clinical), or some other related field that they would like to read about, let me know in comments or email, and I'll post on it. I'm not getting many visitors right now, so I may end up just posting about what interests me in those fields, but I'm up for suggestions. I'll list some potential topics below, in case something strikes a reader's fancy.

- Memory, including:

- False memories/repressed and recovered memories

- Schematic memory

- Working memory, including its role in other cognitive processes (e.g., reasoning, analogy, or decision making)

- Decision making, particularly:

- Goals: what are they, and how do they influence preference

- Intertemporal choice

- The role of analogy in decision making

- Analogy

- Models of analogy

- Analogy and memory

- Analogical reasoning

- Analogy and metaphor

- Analogy and similarity

- Language

- Language evolution

- Language and thought/linguistic determinism/Sapir-Whorf

- Figurative language (metaphor, idioms, metonymy, etc.)

- Polysemy

- Concepts and Categorization

- Theories of concepts

- Conceptual combination

- Types of concepts

- Reason and Emotion

- Consciousness

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Embodied Cognition

- Knowledge Representation (in particular, the status of "representations" in cognitive science)

- The big debates (nature v. nurture, rule-based v. similarity-based, computation v. something else, symbolic vs. connectionist, etc.)

Birthday Post

How Unclever People Can Use Analogies Cleverly

Analogies are powerful reasoning and rhetorical tools, often capable of convincing even when they lack substance or justification. Simply making a comparison can create inferences that are otherwise unlicensed. Here are two examples, from a recent post by Keith Burgess-Jackson:

If one actually considers the structure and mappings in these analogies, they make no sense. Still, it's likely that they are rhetorically powerful. Why is that? First, let's look at the structure of the analogies. The structure of the first analogy seems to be something like this:

The inference we're supposed to make from the Base to the Target is that the situation in the Target is not unfair, either, because the fairness of the Base and Target follow from the same set of relations. Obviously it's not true that the relations in the two domains are even remotely analogous except at the most abstract level. Gay people can marry. However, they can't marry members of the same sex. Dogs, on the other hand, can't vote for humans but not dogs. Furthermore, the difference in sexual orientation is hardly analogous to the difference in species. They are entirely different types of relations.

The second analogy doesn't fair any better. Obviously, gay couples are not biologically incapable of marrying, as men are biologically incapable of having an abortion. What is the real point of Burgess-Jackson's analogies, then? To compare the fairness of denying gay's the right to marriage to cases in which it would be absurd to call something unfair. The only premise required for making these comparisons is the one that they are trying to prove, namely that "Only straight people can marry, therefore denying gay people the right to marry is not unfair." While neither analogy presents a rational argument for Burgess-Jackson's position, because they presuppose that position and the analogies don't hold, simply making the comparison to absurd cases allows people to make the inference that calling anti-gay marriage laws unfair is absurd as well. Now that's good framing.

- The unfairness of denying gay couples the right to marriage is like the unfairness of denying dogs the right to vote.

- The unfairness of denying gay couples the right to marriage is like the unfairness of denying men the ability to have an aborition.

If one actually considers the structure and mappings in these analogies, they make no sense. Still, it's likely that they are rhetorically powerful. Why is that? First, let's look at the structure of the analogies. The structure of the first analogy seems to be something like this:

Base: "Only humans can vote. Dogs are not humans. Therefore dogs cannot vote, and this is not unfair."

Is analogous to:

Target: "Only straight people can marry. Gay people are not straight. Therefore, gay people cannot marry."

The inference we're supposed to make from the Base to the Target is that the situation in the Target is not unfair, either, because the fairness of the Base and Target follow from the same set of relations. Obviously it's not true that the relations in the two domains are even remotely analogous except at the most abstract level. Gay people can marry. However, they can't marry members of the same sex. Dogs, on the other hand, can't vote for humans but not dogs. Furthermore, the difference in sexual orientation is hardly analogous to the difference in species. They are entirely different types of relations.

The second analogy doesn't fair any better. Obviously, gay couples are not biologically incapable of marrying, as men are biologically incapable of having an abortion. What is the real point of Burgess-Jackson's analogies, then? To compare the fairness of denying gay's the right to marriage to cases in which it would be absurd to call something unfair. The only premise required for making these comparisons is the one that they are trying to prove, namely that "Only straight people can marry, therefore denying gay people the right to marry is not unfair." While neither analogy presents a rational argument for Burgess-Jackson's position, because they presuppose that position and the analogies don't hold, simply making the comparison to absurd cases allows people to make the inference that calling anti-gay marriage laws unfair is absurd as well. Now that's good framing.

Thursday, October 28, 2004

Once More into the Breach

OK, this is my last post about Lakoff before the elections, but someone has to clear up some misconceptions. So here goes:

So, there you have it, three misconceptions, and three attempts to explain why they're wrong. I hope this helps. More than likely, conservatives will still see "framing" as synonymous with "spinning," and "Nurturant Parent" as a label for a feminine world-view. In part, this is because Lakoff's own inadequate descriptions of the prototypical conservative and liberal world-views (both of which are thoroughly critiqued here and here). If I were a conservative, I would be offended by his caricature of me, or at least of the prototype of my political world-view, as well. Lakoff's larger point is an excellent one, but as I've said on many occasions, his own use of it is highly problematic, and in most cases, highly impractical as well.

UPDATE: I just realized that I left out the reference to the Rosch and Mervis paper, which I'd meant to include in a footnote. This is what I get for blogging in a fit of insomnia. It's a shame, too, because this paper is one of the classic papers in cognitive science, and presents some excellent experiments which have inspired many future experiments. Anyone interested in cognitive science in general, and concept research in general, should read the paper. So, here it is:

1 Rosch, E., & Mervis, C.B. (1975). Family resemblances: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573-605. There is a draft of a good paper on prototypes by James Hampton here, as well.

- "Strict Father" and "Nuturant Parent" moralities are meant to describe all conservatives and liberals. This is not in fact the case. Instead, they are meant as prototypes around which conservative and liberal world-views cluster. Lakoff's work draws heavily on Prototype Theories of concepts popularized in the 1970s by Rosch and Mervis1. In these theories, prototypes are central tendencies, or mean or median instance of a concept abstracted across many instances of the concept. The features represented in the prototype are the most characterisic (in the sense of being present in the most instances) of the concept. Some instances of a concept are more typical than others by virtue of sharing more of these characteristic features. However, some members of a category will, in fact, share very few of the characteristic features. Thus, under the prototype view of concepts, instances of a concept have a "family resemblance" to each other, rather than sharing necessary and sufficient features, and some members of a category will actually be more similar to members of a contrasting category than to members of the same category. The classic example used to illustrate prototype theories is the concept BIRD. A robin is a highly typical instance of the BIRD concept (at least for people raised in the United States), while the emu is not. Bats share many perceptual features with birds, and few features with many mammals, but are in fact highly untypical members of the concept MAMMAL rather than fairly typical members of the concept BIRD. There are a lot of problems with prototype theories (e.g., how do you explain bats as mammals without some sort of causal theoryl or definitional property?), making Lakoff's reliance on them troublesome, but it's important to realize that this is what his two moral metaphors are. For more on Lakoff's view of concepts, and how it relates to his political theories, read Chapter 17 of his Moral Politics, as well as this excellent post at Semantic Compositions.

- "Nurturant Parent" means "Nurturant Mother." This seems to be a common misconception, and it has been argued against well here and here. Lakoff uses the term "parent" instead of "mother" in order to avoid this misconception, but in a way he brings it on himself. By contrasting "Nurturant Parent" with "Strict Father" morality, he naturally invites the father-mother contrast. However, the Nurturant Parent is meant to embody both feminine and masculine traints. Here is a short characterization of the Nurturant Parent world-view from Lakoff:

In the Nurturant Parent family, it is assumed that the world is basically good. And, however dangerous and difficult the world may be at present, it can be made better, and it is your responsibility to help make it better. Correspondingly, children are born good, and parents can make them better, and it is their responsibility to do so. Both parents (if there are two) are responsible for running the household and raising the children, although they may divide their activities. The parents' job is to be responsive to their children, nurture them, and raise their children to nurture others.Nurturance requires empathy and responsibility.

As this description makes clear, the use of the term "parent" instead of "mother" is not just meant to clear up confusion, but also to highlight the fact that within the nurturant parent world-view, both parents take part in child rearing on an equal footing with similar roles. The use of "Father" in Strict Father morality, while it may invite confusion, is meant to contrast the conservative "paternalistic" world-view with this less male-dominant one.

- "Framing" is a clever euphemism for "spinning." This seems to be the almost universal reaction to Lakoff's political theory among conservatives, but is also shared by some liberals. It's probably true that Lakoff's advice and techniques could be used for spin, but that is not what he advocates at all. Instead, what Lakoff wants liberals to do is to start describing their views in terms of their values, something he thinks Republicans do (often deceptively) very well. Here is a short description of the project and the reason it's needed:

Progressives must rethink their policy goals in terms of values. There are always underlying moral reasons for supporting certain policies and opposing others. The first task then becomes identifying the values behind any given policy.

The temptation for progressives is usually to talk about policies in terms of statistics: affirmative action is necessary because African Americans make up 14.7% of the current college-aged population but only 8% of college students. Seat belt laws are needed because 9,200 people died needlessly in motor vehicle accidents in 2000, and because injuries to less than one-half of 1% of the population cost the rest of us $26 billion. This may be true. But eyes and ears glaze over at statistics if they aren’t contextualized in terms of values. The question progressives don’t often answer explicitly is: Why do these statistics matter to us?

Lakoff feels that an exclusive focus on the facts, without detailing the values that make facts "good" or "bad," puts liberals at a disadvantage. Instead of "spinning" the facts, then, he wants liberals to include a description of why the facts matter from the perspective of liberal values. This is what he means by "framing." And this is why he sees "framing" in terms of values as important:

Americans believe that leaders should have a moral core that informs what they do. This moral core is seen as more important than one’s stance on any particular issue. George W. Bush is perhaps the best example of this in recent memory. He summed it all up in the 2000 campaign, when, after facing criticism for his lack of mastery of foreign policy details, he responded: “I may not know where Kosovo is, but I know what I believe.”

Progressives hear this and tear their hair out: How could the President of the United States actually boast about his lack of knowledge? And who really cares what he believes if he doesn’t know what he’s doing?

For better or for worse, however, most Americans do believe that values are important when choosing leaders. This shouldn’t surprise us, given that the American democratic system—in contrast to so many European democracies—involves choosing a person, rather than a party. Parties are about policies, but people are about values.

So, there you have it, three misconceptions, and three attempts to explain why they're wrong. I hope this helps. More than likely, conservatives will still see "framing" as synonymous with "spinning," and "Nurturant Parent" as a label for a feminine world-view. In part, this is because Lakoff's own inadequate descriptions of the prototypical conservative and liberal world-views (both of which are thoroughly critiqued here and here). If I were a conservative, I would be offended by his caricature of me, or at least of the prototype of my political world-view, as well. Lakoff's larger point is an excellent one, but as I've said on many occasions, his own use of it is highly problematic, and in most cases, highly impractical as well.

UPDATE: I just realized that I left out the reference to the Rosch and Mervis paper, which I'd meant to include in a footnote. This is what I get for blogging in a fit of insomnia. It's a shame, too, because this paper is one of the classic papers in cognitive science, and presents some excellent experiments which have inspired many future experiments. Anyone interested in cognitive science in general, and concept research in general, should read the paper. So, here it is:

1 Rosch, E., & Mervis, C.B. (1975). Family resemblances: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573-605. There is a draft of a good paper on prototypes by James Hampton here, as well.

Wednesday, October 27, 2004

What She Said

Once again, I have just read something that demands comment, but someone smarter than me has already done so better than I could. So, my main comment is: what she said. This is in response to Will Wilkinson's poorly thought-out post, of course.

I started to say something more, but then I saw that it had already been said in the comments at the above link. For instance:

and

The point, then, is that Wilkinson is apparently unacquainted with reality, and with the realities of traditionally disenfranchised groups like African Americans and individuals with low socio-economic status in particular. It is probably true that most voters, be they discriminated against through various means of disenfranchisement or not, are uninformed and therefore do not improve the effectiveness of the democratic process. Still, Wilkinson has no reason to think that the voting groups that are more likely to be intimidated are composed of higher percentages of uninformed voters. There simply is no a priori reason to think that these voters' voices are less deserving of being heard than anyone else's, including Wilkinson's, and his insistence that they are smacks of either racism or simple, unadulterated ignorance. In fact, I'd go so far to say that if Wilkinson's post is an indication of his own informedness, then he's the one whose vote can only detract from the effectiveness of the democratic process.

OK, so I did comment, but only by repeating what someone else had already said. I told you I couldn't say it better. Oh, and go Red Sox!

I started to say something more, but then I saw that it had already been said in the comments at the above link. For instance:

The issue isn't whether increased voter turnout is intrinsically valuable. This is an issue of basic fairness. Some citizens face much greater obstacles to voting than others. If an eligible citizen wants to vote, they have a right to do so.

and

I don't think that we have any reason to believe that the people who are discouraged by voter intimidation are less informed than their voting counterparts. In order to support your hypothesis, you would have to show not only that the groups targeted by voter suppression are less informed, but also that those who succumb to voter suppression are less informed than other members of the target demographic who manage to vote anyway. I'm just not aware of any data to support such a bold conjecture.

The point, then, is that Wilkinson is apparently unacquainted with reality, and with the realities of traditionally disenfranchised groups like African Americans and individuals with low socio-economic status in particular. It is probably true that most voters, be they discriminated against through various means of disenfranchisement or not, are uninformed and therefore do not improve the effectiveness of the democratic process. Still, Wilkinson has no reason to think that the voting groups that are more likely to be intimidated are composed of higher percentages of uninformed voters. There simply is no a priori reason to think that these voters' voices are less deserving of being heard than anyone else's, including Wilkinson's, and his insistence that they are smacks of either racism or simple, unadulterated ignorance. In fact, I'd go so far to say that if Wilkinson's post is an indication of his own informedness, then he's the one whose vote can only detract from the effectiveness of the democratic process.

OK, so I did comment, but only by repeating what someone else had already said. I told you I couldn't say it better. Oh, and go Red Sox!

Tuesday, October 26, 2004

When Intellectual Innovators Become the Status Quo

Brian Leiter's email exchange with Jerry Fodor on the definition of analytic philosophy has generated a great deal of discussion. One comment to the post, by Jason Stanley, has generated still more discussion at Crooked Timber. Here is Jason's comment:

Ortega y Gasset, in his generational theory of history, posited that at any given time in history, there are three generations, each with its own episteme and ethos. The oldest generation has been supplanted by the middle generation, which is the current dominant paradigm, but which is constantly being undermined by the youngest generation. It seems to me like this has always been the way things have worked in the history of ideas: each successive generation works to overcome and supplant its immediate predecessor, and once it has done so, it becomes the status quo. Sometimes, the middle generation has trouble letting go of its subversive attitude, as Jason noted in his comment. For instance, Noam Chomsky and others in his generation revolutionized the way we view the mind and human beings in general, and it must have been a big rush to do so. Now that their ideas have become the status quo, I imagine it's a bit of a let down. Of course, in many ways, and on many fronts, they are already being supplanted, so while they feel they are still they rebels, they are actually the target of new rebellions.

I wonder why it is that things tend to work out that way, particularly in intellectual spheres such as science and philosophy. I'm sure one reason is that it's easier to criticize than defend complex ideas, as any undergraduate who has written papers on famous philosophers has learned. Also, the best way to make a name for oneself is to supplant accepted ideas. However, I think the biggest reason for the constant flow of intellectual upheaval is that every system of ideas is flawed, and the people best equipped to notice the flaws in any system are those who are not fully invested in it. Someone (maybe Plank?) once remarked that the best way for a new theory to gain acceptance is for all of its detractors to die. That may be a bit extreme, but I think it captures this key aspect of the intellectual world: for new theories to gain prominence, the theories they have supplanted have to be widely questioned by those who have not spent their lives formulating and defending them.

There is a certain kind of very influential academic who has a difficult time recognizing that they are no longer a rebellious figure courageously struggling against the tide of contemporary opinion, but rather have already successfully directed the tide along the path of their choice. Chomsky is one such academic, and Fodor is another.

Ortega y Gasset, in his generational theory of history, posited that at any given time in history, there are three generations, each with its own episteme and ethos. The oldest generation has been supplanted by the middle generation, which is the current dominant paradigm, but which is constantly being undermined by the youngest generation. It seems to me like this has always been the way things have worked in the history of ideas: each successive generation works to overcome and supplant its immediate predecessor, and once it has done so, it becomes the status quo. Sometimes, the middle generation has trouble letting go of its subversive attitude, as Jason noted in his comment. For instance, Noam Chomsky and others in his generation revolutionized the way we view the mind and human beings in general, and it must have been a big rush to do so. Now that their ideas have become the status quo, I imagine it's a bit of a let down. Of course, in many ways, and on many fronts, they are already being supplanted, so while they feel they are still they rebels, they are actually the target of new rebellions.

I wonder why it is that things tend to work out that way, particularly in intellectual spheres such as science and philosophy. I'm sure one reason is that it's easier to criticize than defend complex ideas, as any undergraduate who has written papers on famous philosophers has learned. Also, the best way to make a name for oneself is to supplant accepted ideas. However, I think the biggest reason for the constant flow of intellectual upheaval is that every system of ideas is flawed, and the people best equipped to notice the flaws in any system are those who are not fully invested in it. Someone (maybe Plank?) once remarked that the best way for a new theory to gain acceptance is for all of its detractors to die. That may be a bit extreme, but I think it captures this key aspect of the intellectual world: for new theories to gain prominence, the theories they have supplanted have to be widely questioned by those who have not spent their lives formulating and defending them.

Monday, October 25, 2004

Philosopher' Carnival IV: This Time, It's Personal

The 4th Philosophers' Carnival is up at Doing Things With Words. I like the posts at Majikthise on Quine, Mormon Metaphysics on Derrida (Clark Goble actually wrote several on Derrida in the week or so after his death, and they were all very good), and PEA Soup on moral luck. Head over and read them all. I even have a post in this edition of Carnival, but I'm not quite sure how. I don't recall submitting it, but I have been known to blog in my sleep.

Sunday, October 24, 2004

The Vatican is Pissed, But It Still Has the U.S.

I must admit that earlier this week, I was happy to read that the Vatican is upset about what it perceives as increasing secularization in European politics. The Vatican released the following remarks:

The Vatican expressed these sentiments in response to the EU Parliament's rejection of Italy's nomination of Rocco Buttiglione, who has publically voiced anti-gay and misogynistic sentiments. The Vatican further lamented the fact that "government after government [has approved] measures on abortion, family law and scientific study that run counter to Catholic teaching." So, the Vatican is upset that, contrary to its teachings, European governments and the E.U. are acting to counter discrimination against gays and women, and funding stem-cell research that will ultimately benefit mankind as a whole. If these are the sorts of things that upset the Vatican, then I can only be happy when I hear that the Vatican is upset. The histrionics the Church, and Cardinal Martino, have displayed in calling these trends in Europe signs of a "lay Inquisition" only make their disappointment seem that much sweeter, as they absurdly cast progressive policies as motivated by anti-Catholic sentiments.

Across the pond, the Vatican can only smile at the way things are going in the U.S. Abortion rights are coming under increasingly intense fire, and with Supreme Court positions likely to open up in the next few years, the Church and other anti-choice activists can only be salivating at the mouth. The U.S.'s stance on embryonic stem cell research and gay marriage must be a point of pride for the Church as well. Then there's the "Constitution Restoration Act of 2004," which states:

Rest assured, Vatican, there is no "lay Inquisition" here. We're working hard to retain your regressive, antiquated values, and so far, it looks like we're succeeding. "Secular" remains a four letter word here, and if the backers of the CRA have their way, it will be against the law, too.

"It looks like a new Inquisition. It is a lay Inquisition, but it is so nasty," Cardinal Renato Martino, who heads the Vatican's Council for Justice and Peace, told reporters this week in response to the dispute. "You can freely insult and attack Catholics and nobody will say anything. If you do so for other confessions, let's see what would happen."

The Vatican expressed these sentiments in response to the EU Parliament's rejection of Italy's nomination of Rocco Buttiglione, who has publically voiced anti-gay and misogynistic sentiments. The Vatican further lamented the fact that "government after government [has approved] measures on abortion, family law and scientific study that run counter to Catholic teaching." So, the Vatican is upset that, contrary to its teachings, European governments and the E.U. are acting to counter discrimination against gays and women, and funding stem-cell research that will ultimately benefit mankind as a whole. If these are the sorts of things that upset the Vatican, then I can only be happy when I hear that the Vatican is upset. The histrionics the Church, and Cardinal Martino, have displayed in calling these trends in Europe signs of a "lay Inquisition" only make their disappointment seem that much sweeter, as they absurdly cast progressive policies as motivated by anti-Catholic sentiments.

Across the pond, the Vatican can only smile at the way things are going in the U.S. Abortion rights are coming under increasingly intense fire, and with Supreme Court positions likely to open up in the next few years, the Church and other anti-choice activists can only be salivating at the mouth. The U.S.'s stance on embryonic stem cell research and gay marriage must be a point of pride for the Church as well. Then there's the "Constitution Restoration Act of 2004," which states:

`Notwithstanding any other provision of this chapter, the Supreme Court shall not have jurisdiction to review, by appeal, writ of certiorari, or otherwise, any matter to the extent that relief is sought against an element of Federal, State, or local government, or against an officer of Federal, State, or local government (whether or not acting in official personal capacity), by reason of that element's or officer's acknowledgement of God as the sovereign source of law, liberty, or government.'.

Rest assured, Vatican, there is no "lay Inquisition" here. We're working hard to retain your regressive, antiquated values, and so far, it looks like we're succeeding. "Secular" remains a four letter word here, and if the backers of the CRA have their way, it will be against the law, too.

Happy Birthday Universe!

Yesterday, the Universe turned 6007. Happy Birthday Universe! And thank you, Bishop Ussher, for that little bit of nonsense.

The Neuroscience of Repressed Memories

In A Treatise of Human Nature, Hume wrote:

When Hume published the first volume of the Treatise in 1739, he couldn't have known that 260 years later, we would begin to learn that "impressions" (or sensations), and ideas, particularly those of the visual imagination, would turn out to share the same parts of the brain. Not only do they share some of the same brain regions, but there may be little difference in the brain activation caused by vivid impressions (sensations of external objects) and vivid visual images created by the imagination.

This has all sorts of implications for cognitive science. One of the most interesting implications concerns the formation of "false memories," which are now at the forefront of the repressed memory debate. For instance, in arecent study, neuroscientists presented participants with object words and asked to imagine a visual image of the object. Half of the words were followed (2 seconds later) by a picture of the object. While they were looking at the words and pictures, functional MRI scans were taken. Participants studied these words, while being scanned, for seven consecutive phases. Finally, twenty minutes after the last study phase, participants heard words, a third of which had been presented with pictures, a third of which had been presented without pictures, and a third of which had not been presented in the study phases. They were asked to indicate whether they had seen a photo of the object in the study phases.

Researchers have known for some time that producing visual images through imagination can sometimes lead to memory errors, called "reality-monitoring errors" because they fail to distinguish between observed and imagined images. Some of this is likely to be due to retrieval problems, but some also may be due to how visual images, be they imagined or produced by the senses, are encoded. What this study found is that when false memories, or reality-monitoring errors, were produced for words that had been presented without pictures (i.e., when these words were remembered as having been presented with pictures), the brain areas that were active during the study phase (most notably, the precuneus, right parietal, and anterior cingulate regions) overlapped significantly with those active during actual picture presentation. These areas were significantly less active during the presentation of words during the study phase in cases that were subsequently remembered correctly as having been presented without pictures. False memories were produced for study words about four times as often than for words that had not been seen in the study phase.

The lesson, then, is that contrary to Hume, during both in encoding and retrieval, there is often little difference between visual images created by the senses and those created by the imagination, even the images created of objects when reading the words that refer to them (which Hume specifically claims is impossible or at least uncommon). The difference is small enough as to make it difficult to distinguish between sensory and imagined images in memory. What, exactly, this means for the repressed memory debate will require further research, but it clearly demonstrates that there is a neural basis for false memories produced by repeatedly imagining images, for instance through repeated suggestions or rumination. Since we've yet to come up with anything like a neural, or even an algorithmic or representational basis for memory repression of dissociation, this sort of advancement in memory research certainly doesn't bode well for the champions of repressed memory theories and recovered memory therapies.

All the perceptions of the human mind resolve themselves into two distinct kinds, which I shall call IMPRESSIONS and IDEAS. The difference betwixt these consists in the degrees of force and liveliness, with which they strike upon the mind, and make their way into our thought or consciousness. Those perceptions, which enter with most force and violence, we may name impressions: and under this name I comprehend all our sensations, passions and emotions, as they make their first appearance in the soul. By ideas I mean the faint images of these in thinking and reasoning; such as, for instance, are all the perceptions excited by the present discourse, excepting only those which arise from the sight and touch, and excepting the immediate pleasure or uneasiness it may occasion. I believe it will not be very necessary to employ many words in explaining this distinction. Every one of himself will readily perceive the difference betwixt feeling and thinking. The common degrees of these are easily distinguished; tho' it is not impossible but in particular instances they may very nearly approach to each other. Thus in sleep, in a fever, in madness, or in any very violent emotions of soul, our ideas may approach to our impressions, As on the other hand it sometimes happens, that our impressions are so faint and low, that we cannot distinguish them from our ideas. But notwithstanding this near resemblance in a few instances, they are in general so very different, that no-one can make a scruple to rank them under distinct heads, and assign to each a peculiar name to mark the difference.

When Hume published the first volume of the Treatise in 1739, he couldn't have known that 260 years later, we would begin to learn that "impressions" (or sensations), and ideas, particularly those of the visual imagination, would turn out to share the same parts of the brain. Not only do they share some of the same brain regions, but there may be little difference in the brain activation caused by vivid impressions (sensations of external objects) and vivid visual images created by the imagination.

This has all sorts of implications for cognitive science. One of the most interesting implications concerns the formation of "false memories," which are now at the forefront of the repressed memory debate. For instance, in a

Researchers have known for some time that producing visual images through imagination can sometimes lead to memory errors, called "reality-monitoring errors" because they fail to distinguish between observed and imagined images. Some of this is likely to be due to retrieval problems, but some also may be due to how visual images, be they imagined or produced by the senses, are encoded. What this study found is that when false memories, or reality-monitoring errors, were produced for words that had been presented without pictures (i.e., when these words were remembered as having been presented with pictures), the brain areas that were active during the study phase (most notably, the precuneus, right parietal, and anterior cingulate regions) overlapped significantly with those active during actual picture presentation. These areas were significantly less active during the presentation of words during the study phase in cases that were subsequently remembered correctly as having been presented without pictures. False memories were produced for study words about four times as often than for words that had not been seen in the study phase.

The lesson, then, is that contrary to Hume, during both in encoding and retrieval, there is often little difference between visual images created by the senses and those created by the imagination, even the images created of objects when reading the words that refer to them (which Hume specifically claims is impossible or at least uncommon). The difference is small enough as to make it difficult to distinguish between sensory and imagined images in memory. What, exactly, this means for the repressed memory debate will require further research, but it clearly demonstrates that there is a neural basis for false memories produced by repeatedly imagining images, for instance through repeated suggestions or rumination. Since we've yet to come up with anything like a neural, or even an algorithmic or representational basis for memory repression of dissociation, this sort of advancement in memory research certainly doesn't bode well for the champions of repressed memory theories and recovered memory therapies.

Saturday, October 23, 2004

How Undecided Are Undecideds?

I sometimes wonder how undecided undecided voters really are. Specifically, I wonder whether implicit attitudes that are at least partially independent from self-reported attitudes can predict the behavior of undecided voters. Since the late 70s, psychologists have produced more and more evidence that our introspective experience of our own higher-order cognitive processes and attitudes is highly inaccurate. We don't have direct access to these processes and attitudes, but instead produce theories about them from our behavior, and if our conscious beliefs about them are accurate, it is only because we've come up with a good theory. For this reason, psychologists have produced a wealth of indirect measures of cognitive processes and attitudes that do not rely on subjects' self-reports. One species of indirect tests is designed to test for "implicit attitudes," or attitudes that the subject may not be aware of, and may not accord with their self-reported, or even experienced attitudes. Some of these implicit attitude tests have been shown to be able to predict behavior (e.g., consumer behavior) quite well. I wonder, then, if they might also be able to predict voting behavior, particularly the voting behavior of undecideds.

To see how this would work, I'll briefly describe one implicit attitude test. This test, called the Evaluative Movement Assessment, or EMA1, is built around the idea that people are motivated to approach positively evaluated stimuli, and avoid negatively evaluted stimuli. In addition, for some strange reason (don't ask me why; it's voodoo), these approach/avoidance motivations are active when people are asked to move something toward or away from their names2. In EMA, the participant's name is placed in the center of a computer screen, while words appear on either side of her name. The participant is told to move positive words towards her name, and negative words away from it. In addition, she is told to learn a set of target words, and in each EMA session, she is told to move all of the positive word in one direction (either toward or away from her name). The idea is that response latencies will be greater when participants are told to move positively evaluated target words away from their name, and negatively evaluated words towards their name. After several sessions, the average toward and away scores can be obtained for each target word. The toward scores are then subtracted from the away scores to produce a "valence score," with positively evaluated words having strongly positive valences, and negatively evaluated words having strongly negative valences.

The relationship between implicit attitudes and actual behavior is still somewhat controversial, but implicit attitude tests have been shown to accord with several different types of behavior, including consumer behavior, which is roughly analogous to voting behavior. The idea, then, would be to have undecided voters move the names of candidates and/or political parties towards and away from their names, compute a valence for each candidate, and then use that to predict for whom they will vote. My suspicion is that most undecided voters do have implicit attitudes toward the candidates that are not reflected in their self-reports, and perhaps even in their own beliefs about their attitudes toward the candidates. Furthermore, I suspect that the more positive the implicit attitude toward a candidate is, the more likely an undecided voter is to vote for that candidate, while the more negative the implicit attitude, the less likely a person will be to vote for the candidate.

1 Brendl, C.M., Markman, A.B., & Messner, C. (in press). Indirectly measuring evaluations of several attitude objects in relation to a neutral reference point. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

2 Chen, M., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). Consequences of automatic evaluation: Immediate behavioral predispositions to approach or avoid the stimulus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 215-224.

To see how this would work, I'll briefly describe one implicit attitude test. This test, called the Evaluative Movement Assessment, or EMA1, is built around the idea that people are motivated to approach positively evaluated stimuli, and avoid negatively evaluted stimuli. In addition, for some strange reason (don't ask me why; it's voodoo), these approach/avoidance motivations are active when people are asked to move something toward or away from their names2. In EMA, the participant's name is placed in the center of a computer screen, while words appear on either side of her name. The participant is told to move positive words towards her name, and negative words away from it. In addition, she is told to learn a set of target words, and in each EMA session, she is told to move all of the positive word in one direction (either toward or away from her name). The idea is that response latencies will be greater when participants are told to move positively evaluated target words away from their name, and negatively evaluated words towards their name. After several sessions, the average toward and away scores can be obtained for each target word. The toward scores are then subtracted from the away scores to produce a "valence score," with positively evaluated words having strongly positive valences, and negatively evaluated words having strongly negative valences.

The relationship between implicit attitudes and actual behavior is still somewhat controversial, but implicit attitude tests have been shown to accord with several different types of behavior, including consumer behavior, which is roughly analogous to voting behavior. The idea, then, would be to have undecided voters move the names of candidates and/or political parties towards and away from their names, compute a valence for each candidate, and then use that to predict for whom they will vote. My suspicion is that most undecided voters do have implicit attitudes toward the candidates that are not reflected in their self-reports, and perhaps even in their own beliefs about their attitudes toward the candidates. Furthermore, I suspect that the more positive the implicit attitude toward a candidate is, the more likely an undecided voter is to vote for that candidate, while the more negative the implicit attitude, the less likely a person will be to vote for the candidate.

1 Brendl, C.M., Markman, A.B., & Messner, C. (in press). Indirectly measuring evaluations of several attitude objects in relation to a neutral reference point. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

2 Chen, M., & Bargh, J. A. (1999). Consequences of automatic evaluation: Immediate behavioral predispositions to approach or avoid the stimulus. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 215-224.

Friday, October 22, 2004

Only in the South...

I wish I had words for this, but I don't, other than to say it's damn funny. Here's a blurb:

Once, when I was a kid, a skunk moved into the crawl space beneath our house while we were on vacation. All it changed was the odor of the place, though, so I'm not sure the situations are comparable.

Stranger moves in, redecorates while woman's on vacation

DOUGLASVILLE, Georgia (AP) -- A woman came home from vacation to find a stranger living there, wearing her clothes, changing utilities into her name and even ripping out carpet and repainting a room she didn't like, authorities said.

Once, when I was a kid, a skunk moved into the crawl space beneath our house while we were on vacation. All it changed was the odor of the place, though, so I'm not sure the situations are comparable.

Ignorance or Sins of Memory?

This corner of the blogosophere is abuzz with posts and more post (and still more) about the latest PIPA survey. In that survey, it was discovered that:

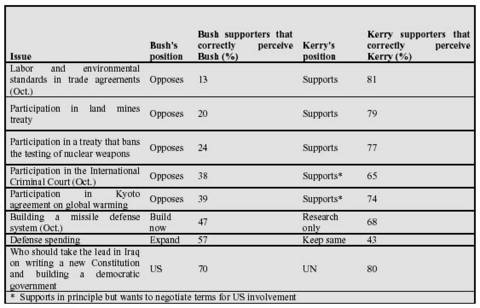

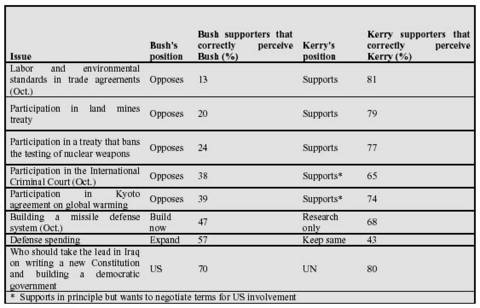

Not only are Bush supporters ignorant of reality in general, but they are also ignorant of the reality of their own candidate, as this table shows:

Click for Larger View.

The second part of the survey, showing that Bush supporters don't know where he stands on some important issues, is interesting, but I'm not exactly sure how to explain it. I imagine a lot of credit for this widespread ignorance can be given to the Bush campaign for effectively hiding what it is that Bush thinks and does. A lot of credit probably goes to the desire to avoid cognitive dissonance, and the confirmation bias, as well. Many of the people who are ignorant about what Bush actually thinks are probably the sort of people who vote Republican in every election, and they have to work hard to justify that vote to themselves, even if it means distorting the views of Republican candidates to make them more consistent with their own.

To me, the first part is more interesting. Last Novemember I saw a talk* on false memories for events and facts about the Iraq war. The researchers asked American, German, and Australian students to report whether certain statements about the Iraq war were true or false. The found that most American students still believed long-since retracted news reports about, e.g., the discovery of WMD and connections between Iraq and Al Qaeda, while German and Australian students by and large recognized these statements as false. It is interesting that simply planting the seeds of these beliefs in the minds of most Americans is sufficient to have them believe it. Thus, the news stories, often reporting information directly from the Bush administration, about the discovery of WMD or Iraq-Al Qaeda connections served to create beliefs even as subsequent news reports retracted the earlier ones. This is the brilliance of the Republican Party in 2004. They recognize that they don't have to stick to the facts, but they don't have to lie either. All they have to do is make reports that are likely false, but are in accord with sketchy information, and even if it is later shown that the reports are in fact false, people will still believe them.

Why is it that Americans, in this study, were more gullible than Germans or Australians? I suspect that the opposite would have been the case had evidence of WMD and Iraq-Al Qaeda connections had been discovered. The early reports showing no connection would have been widely believed by Germans and Australians, who were primed by their anti-war attitudes to believe anti-war facts. Americans, in turn, primed by their pro-war sentiments, were more likely to believe information consistent with those sentiments. Such is the human mind. This is the reason that I am much less surprised than the other liberal bloggers seem to be at Republican ignorance. I know how susceptible we (as a group) are to such ignorance, as well. After all, Republicans are humanoids, sort of like us.

* I can't for the life of me remember who gave the talk. It was in one of the Saturday (morning, I think) memory sessions at the 2003 meeting of the Psychonomic Society, in Vancouver. Maybe someone who reads this blog (yeah right) was there, and saw the talk, or has a schedule from the conference, and can tell me who the hell gave it.

Even after the final report of Charles Duelfer to Congress saying that Iraq did not have a significant WMD program, 72% of Bush supporters continue to believe that Iraq had actual WMD (47%) or a major program for developing them (25%). Fifty-six percent assume that most experts believe Iraq had actual WMD and 57% also assume, incorrectly, that Duelfer concluded Iraq had at least a major WMD program. Kerry supporters hold opposite beliefs on all these points.

Similarly, 75% of Bush supporters continue to believe that Iraq was providing substantial support to al Qaeda, and 63% believe that clear evidence of this support has been found. Sixty percent of Bush supporters assume that this is also the conclusion of most experts, and 55% assume, incorrectly, that this was the conclusion of the 9/11 Commission. Here again, large majorities of Kerry supporters have exactly opposite perceptions.

These are some of the findings of a new study of the differing perceptions of Bush and Kerry supporters, conducted by the Program on International Policy Attitudes and Knowledge Networks, based on polls conducted in September and October

Not only are Bush supporters ignorant of reality in general, but they are also ignorant of the reality of their own candidate, as this table shows:

Click for Larger View.

The second part of the survey, showing that Bush supporters don't know where he stands on some important issues, is interesting, but I'm not exactly sure how to explain it. I imagine a lot of credit for this widespread ignorance can be given to the Bush campaign for effectively hiding what it is that Bush thinks and does. A lot of credit probably goes to the desire to avoid cognitive dissonance, and the confirmation bias, as well. Many of the people who are ignorant about what Bush actually thinks are probably the sort of people who vote Republican in every election, and they have to work hard to justify that vote to themselves, even if it means distorting the views of Republican candidates to make them more consistent with their own.

To me, the first part is more interesting. Last Novemember I saw a talk* on false memories for events and facts about the Iraq war. The researchers asked American, German, and Australian students to report whether certain statements about the Iraq war were true or false. The found that most American students still believed long-since retracted news reports about, e.g., the discovery of WMD and connections between Iraq and Al Qaeda, while German and Australian students by and large recognized these statements as false. It is interesting that simply planting the seeds of these beliefs in the minds of most Americans is sufficient to have them believe it. Thus, the news stories, often reporting information directly from the Bush administration, about the discovery of WMD or Iraq-Al Qaeda connections served to create beliefs even as subsequent news reports retracted the earlier ones. This is the brilliance of the Republican Party in 2004. They recognize that they don't have to stick to the facts, but they don't have to lie either. All they have to do is make reports that are likely false, but are in accord with sketchy information, and even if it is later shown that the reports are in fact false, people will still believe them.