Evolution education is an interesting case for education researchers and cognitive scientists because there are so many of what you might call non-epistemic factors at play. For example, a study by Brem et al. a few years ago found that across the spectrum from creationist to evolutionist, college students tended to believe that evolution will have negative psychological and social consequences1. It's likely that for many, belief in these negative consequences influences not only their willingness to believe in evolution, but also their willingness to expose themselves to information about it, or to attempt to understand that information. There are also many social or familial factors at play. To explain differences in the developmental paths towards creationism vs. evolutionism, Margaret Evans has proposed a "model of constructive interactionism," in which "children generate intuitive beliefs about origins, both natural and intentional, while communities privilege certain beliefs and inhibit others, thus engendering diverse belief systems"2. In other words, children come to the table with certain intuitions about the origins of things (I'll discuss those intuitions in a bit), and socialization and education processes serve to encourage some of those intuitions while de-emphasizing others. Thus, children in strong creationist families will have their intuitions that are directly opposed to evolution encouraged, making the job of science educators even more difficult. In this post, I'm going to describe three of of the intuitions and biases that are directly relevant to how children and adults think about evolution, because I find them to be the most interesting.

Intuitive Theists

There is a growing body of evidence indicating that children are inclined to view both artifacts and natural kinds (biological and non-biological) as existing for a purpose, and to believe that they were intentionally created for that purpose. Here is Deborah Kelemen describing some of the research indicating children's inclination to believe that natural kinds have a purpose3:

Consistent with the view that from very early on, teleological assumptions constrain our reasoning about living things, studies have found that young children attend to shared functional adaptation rather than shared overall appearance (or category membership) when generalizing behaviors to novel animals (Kelemen et al., 2003a), judge whether biological properties are heritable based on their functional consequences rather than their origin and explain body properties by reference to their self-serving functions not their physical-mechanical cause.The objects to which children will attribute a purpose range from animal parts (e.g., legs are for walking) to whole animals (lions exist "to go in the zoo"), and even non-biological kinds (clouds exist to make rain). In addition, when asked whether someone created the first of a particular item, children are likely to answer yes for all three kinds of objects (artifacts, biological kinds, and non-biological natural kinds)4. It's understandable, then, why evolution should be difficult to teach to children: it is counterintuitive. Both the non-teleological aspects of evolutionary explanations of the origins of biological kinds, and the lack of a need for an intelligent designer go against children's natural view of things.

But the story is actually somewhat worse for evolution than intuitions about purpose and intentional creation indicate. While evolution involves non-teleological processes, teleological language is still pretty common in discussions of evolution (even Darwin used it), and many adults who believe in various intelligent design philosophies insist that the intelligent design position is not inconsistent with evolutionary biology. But children's intuitions may be more specific than simply inferring teleology and purposeful creation. They may actually be creationists, at least at certain ages. Margaret Evans has explored the beliefs of children in both fundamentalist Christian and non-fundamentalist households, and found an interesting, and for educators, somewhat disturbing pattern5. In her study, children under the age of 8 in fundamentalist households tended to be strict creationists: they believed that a non-human intelligent entity (God) created all animals as they are now, while children under the age of 8 in non-fundamentalist homes held beliefs that Evans describes as a mixture of creationism and "generationist" origins (such as "the first robins came from eggs); between the ages of 8 and 10 years, children were strict creationists, regardless of the type of household; and from 11 on, children in fundamentalist households tended to be strict creationists, while children in non-fundamentalist homes tended to be evolutionists. Thus it appears that education can, in older children, overcome creationist intuitions, but only if that education is consistent (or at least not inconsistent) with what children are being taught in the home.

The work of Kelemen and Evans helps to explain why evolution has had such a hard time becoming widely accepted by the general public. From an early age, our intuitions run counter to evolutionary science, and unless children live in homes where evolution is not seen as being counter to the belief systems of their parents, they will not let go of those intuitions, even when they are taught about evolution in school. Those children will then go on to privilege those same intuitions in their children, and so on, leading to generation after generation of individuals who, by the time they are college-aged, will find it very difficult to accept any evolutionary teachings.

Intuitive Essentialists

In what's now a classic paper, Medin and Ortony6 argued that humans may be intuitive essentialists. They called this position "psychological essentialism," and there is a growing body of evidence indicating that they were right. We are essentialists, especially about natural kinds, and biological kinds in particular, from a very young age. It may not seem so at first, but this fact could have very important implications for evolution education, and the willingness, perhaps even the ability, of many people to accept evolution as an explanation of biological origins.

Here is how Gelman and Markman expressed what later became the psychological essentialism position7:

Natural kinds are categories of objects and substances that are found in nature (e.g., tiger, water, cactus)... natural kind terms capture regularities in nature that go beyond intuitive similarity... Natural kinds have a deep, nonobvious basis; perceptual features, though useful for identifying members of a category, do not always serve to define the category. For example, "fool's gold" looks just like gold to most people, yet we accept the statement of an expert that it is not gold... Because natural kinds capture theory-based properties rather than superficial features, some of the properties that were originally used to pick out category members can be violated, but we still agree the object is a member of the kind if there is reason to believe that "deeper," more explanatory properties still hold. (p. 1532)In other words, people believe that natural kinds have an underlying, unseen essence that makes them what they are, and that while this essence is likely associated in some causal fashion with the surface features that we usually use to classify an instance of a kind, the essence remains the same regardless of whether the surface features change. For biological kinds, people (including young children) believe that origins (who the parents were) determine the essence of an individual. Thus, when an animal born as a raccoon, to raccoon parents, is painted too look like a skunk, and has a sack containing a stinky substance surgically implanted, children still call it a raccoon8. This belief has implications for how people make inferences about biological kinds, including inferences about origins. For example, in a study with adults, participants heard a story about a fictitious animal, called a "sorp," that has all the prototypical features of a bird (feathers, makes nests, etc.). In the story, the "sorp" falls into a vat of toxic waste, and all of its perceptual features change: its feathers are gone, and it now has wings that look like insect wings, has an insect-like exoskeleton, and so on. It now looks like an insect, not a bird. As the story moves along, the insect-like sorp mates with a normal sorp. The participants were then asked whether the offspring of the changed and normal couple will have insect-like or bird-like offspring. They overwhelmingly indicated that the offspring would be more bird-like9.

In a paper published in this month's issue of Cognitive Psychology10, Andrew Shtulman argues that essentialist thinking may have implications for how people understand evolution. He writes:

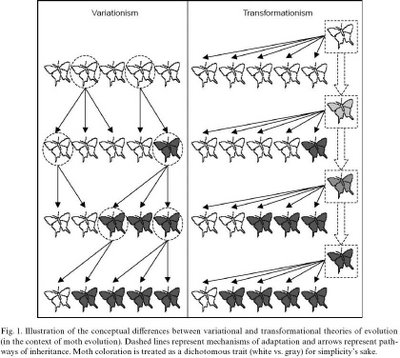

Applied to the study of biological adaptation, essentialism led early evolutionary theorists to commit what Gould (1996) calls the “fallacy of reified variation,” or the tendency “to abstract a single ideal or average as the essence of a system and to devalue or ignore variation among the individuals that constitute the full population” (p. 40). These theorists construed evolution as the process by which a species’ essence is transformed over time, and they proposed a variety of essence-transformation mechanisms, including the inheritance of acquired traits (Lamarck, 1809), the unfolding of a preprogrammed design (Chambers, 1844), the recapitulation of ontogeny (Haeckel, 1876), the acceleration of growth (Cope, 1896), the chemical structure of protoplasm (Berg, 1926), the lawful properties of organic matter (Eimer, 1898), the intentional properties of intelligent systems (Butler, 1916), and an élan vital (Bergson, 1911). (pp. 172-173)Shtulman lumps these positions together under the heading of "transformationalism." Darwin, Shtulman argues, was so important because he was able to overcome the intuitive essentialist thinking that dominated the work of these and many other natural scientists, and thus overcome transformationalism. His theory embodies what Shtulman calls variationism, which he describes as (referencing the figure below):

First, chance mutations and sexual recombinations create indidifferencessrences among members of the same species (depicted in the left handfthand panel of Fig. 1 as arrows between parents and offspring of different colors). Second, some of these individual differences are retained and others are eliminated on the basis of their utility to survival and reproduction (depicted by circles around the few organisms that produce offspring.Shtulman illustrates the differences between the two positions with this diagram:

Notice how in the transformationalist diagram, the color of some of the moths changes slowly over generations (presumably to a more and more adaptive color), while in the variationist diagram, one-time mutations create variability in the population of moths that is passed on from generation to generation, with the new color becoming more common in the population because it is more adaptive.

Most of us, unfortunately, are not Darwins, and overcoming such deeply ingrained intuitive biases may not come easy to us, even after years of science education. Shtulman presents data in his paper showing that both high school and college students (though not evolutionary biologists), tend to consistently give transformationalist answers to questions about origins and adaptation. Thus, it appears that in a very important way, our intuitive essentialist beliefs about biological kinds make it difficult for us to understand how evolution works.

The Value of Beliefs

Many factors man contribute to the value of particular beliefs. Howevrecentecents study by Jesse Preston and Nicholas Epley11 demonstrates two factors that may be of particular importance in the relationship between evolution and some religious beliefs (e.g., those held by 53% of the American public, according to the survey linked above). They showed that when people are asked to explain things with a belief, the perceived value of that belief goes up, whereas when people are asked to explain a belief, the perceived value goes down. They interpret this as showing that the value of a belief is, at least in part, determined by its position in a causal or explanatory sequence. If the belief explains a lot of other facts and beliefs, then it is valuable, whereas if it is explained by other facts or beliefs, it becomes less valuable. In one of their experiments, they explicitly looked at what they called "cherished beliefs," in this case, beliefs about God. Participants were divided into four groups. Two groups were asked to list things that belief in God could explain, with one group asked to give three and one ten things. The other two groups were asked to list either 3 or 10 observations that could explain God's "behavior." Overall, participants who believed in God (self-reported atheists were excluded) had a difficult time listing observations that could explain God's behavior, but when they did, whether they listed 3 or 10, their ratings of their belief in God were lower than the participants in the applications conditions. Preston and Epley argue that the difficulty participants had in providing observations that explain God's behavior may be a result of the fact that people have a hard time coming up with explanations for highly valued beliefs, because these explanations would devalue beliefseleifs.

The implications of these findings for evolution education should be obvious. For many who believe that God produce biological kinds, and humans specifically, in their present form, an alternative explanation, even if it is possible to say that it was the work of God, will serve to devalue that belief, by relegating it to a lower position in the explanatory system. Thus, the very nature of our relationship to beliefs we hold valuable may make evolution education more difficult, particularly for people raised in in fundamentalist traditions.

Conclusions

So that's my contribution. I've presented three factors that make the job of biology teachers more difficult when they're trying to teach evolution, either to children or adults.

- Intuitive theism, in which our intuitions lead us to make design inferences about complex kinds or under conditions of uncertainty; intuitions that can be reinforced culturally to an extent that it may be almost impossible to overcome them by the time we reach adulthood.

- Intuitive essentialism, which causes us to believe that biological kinds have hidden internal essences which determine what they are, how they will behave, and what features they should have, and which may make us interpret evidence of adaptation in transformationalist, rather than Darwinian/modern biological varationist terms.

- The role of explanatory power in determining the value of beliefs, and the fact that we may resist explaining our most cherished beliefs in order to avoid devaluing them.

1Brem, S.K., Ranney, M., & Schind, J. (2002). Perceived consequences of evolution: College students perceived negative personal and social impact in evolutionary theory. Science Education, 87(2), 181-206.

2Evans, E.M. (2001). Cognitive and contextual factors in the emergence of diverse belief systems: creation versus evolution. Cognitive Psychology, 42(3), 217-266.

3Kelemen, D. (2004). Are children 'intuitive theists'?: Reasoning about purpose and design in nature. Psychological Science, 15(5), 295-301.

4Kelemen, D., & DiYanni, C. (2005). Intuitions about origins: Purpose and intelligent design in children's reasoning about nature. Journal of Cognition and Development, 6(1), 3-31.

5Evans, E. M. (2001). Cognitive and contextual factors in the emergence of diverse belief systems: Creation versus evolution. Cognitive Psychology, 42, 217-266.

6Medin, D. L., & Ortony, A. (1989). Psychological essentialism. In S. Vosniadou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and Analogical Reasoning, Cambridge, 179Ã?–195 .

7Gelman, S.A., & Markman, M. (1986). Young children's inductions from natural kinds: The role of categories and appearances. Child Development, 58, 1532-1541.

8Keil, F.C. (1989). Concepts, Kinds, and Cognitive Development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

9Rips, L. J. (1989). Similarity, typicality, and categorization. In S. Vosniadou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and Analogical Reasoning. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21-59.

10Shtulman, A. (2006). Qualitative differences between naïve and scientific theories of evolution. Cognitive Psychology, 52, 170-194.

11Preston, J., & Epley, N. (2005). Explanations versus applications: The explanatory power of valuable beliefs. Psychological Science, 18, 826-832.

24 comments:

Or, in Mayr's terms - "population thinking". I agree, it is the key.

You need to send this article to Tangled Bank, Teaching Carnival and Carnival of Education, so many more people get to read this important post.

It's kind of funny. I was intuitively aware of the belief valuation issue before I read this post. I've talked to theistic friends about God, and I think that by far, the most productive discussions I've had have been those where I explain how a secular worldview can accomodate the values and psychological comforts of theism without the theistic beliefs. (For instance, how atheists can be moral.) It seems to me like repeated exposure to these alternate explanations should make a belief in God less necessary for one to maintain other parts of one's worldview that are independently valuable, and thus make one less confident in one's theism and more open to agnosticism and secularism. Do you think this mechanism is plausible, Chris?

Unfortunately, none of that is really addressable in a biology class, but it is addressable, perhaps, in a good quality philosophy of religion class.

Cool post, Chris.

I'll have to dig up Shtulman's actual paper at some point, but I'm not wholly convinced by his argument, as you present it.Darwin didn't overcome intuitive essentialism; he explicitly tells us both that his position includes the Unity of Type position (biological essentialism par excellence) and that it gives the principle of Natural Classification, which is the Holy Grail of natural kind thinking. Darwin's distinction wasn't that he overcame essentialism but that he reversed the order of explanation: the essentialists kept trying to explain teleology in one stage by morphology, whereas Darwin explained morphology (Unity of Type) by teleology (in the form of Cuvier's Conditions of Existence) over uncountably many stages. The notion that Darwin somehow showed that essentialism wasn't viable rather than providing it a scientific basis seems to have come after the first generation of Darwinists. But, then, people use 'essentialism' in many different senses, and I might just not be getting Shtulman's usage. (I also don't really like Shtulman's diagram; essentialists didn't usually hold that generationes were connected to their type by a pathway of inheritance!) But although I don't like the details of Shtulman's argument, I think you are very right that intuitive essentialism plays a role here. (It's an interesting issue, because I know that Susan Oyama spends a considerable part of her book, The Ontogeny of Information, arguing that even among biologists only developmental systems theorists have really rid themselves of essentialist thinking.)

a little off topic...

Allele Drift Day?

Brandon, I can send you a copy of the Shtulman paper, if you'd like.

It goes without saying, but I'll send that paper to anyone who would like to read it. I have copies of a few of the other papers referenced in the post, too, that I can send to anyone interested in reading them (Pdf files).

I was struck, years ago, by a public health official saying, "The question is not 'Why are some people sick?' The question is 'Why isn't everyone sick?' " If we're all exposed to the same influences, why are so many of us embracing evolution as a way of understanding the world?

Why would "intuitive teleology" necessarily imply theism? Why not, for example, a belief in a race of pandimensional hyperintelligent beings? The view that aetiological myths are grounded in intuitive ways of thinking about the world doesn't strike me as especially problematic. The problem that Creationism presents to the science educator is not that it's natural, but that it's cultural, and more to the point, that it is owned by a great many of the students the American science educator is tasked with educating. Counterintuitively, perhaps, the natural tendencies of thought may be more pliable, more transparent, or generally less of an obstacle to education than deeply ingrained cultural systems of belief and value. In this case, teaching against Aesop may prove to be more productive than direct confrontations with religious beliefs.

I really like how you've tied things together here. The diagram from Shtulman is brilliant. Even if we entertain the notion that only the evo-devo people correctly understand the origin of lifeforms, that is, without ever introducing a fallacy of reified variation, the contrast between transformationalist and variationist viewpoints still illuminates a problem of essentialism, perhaps we could say "naive essentialism." Well done.

Fido, thankd for the compliments.

You're absolutely right that the problem is largely cultural, which is what I take Evans' work to be indicating. According to her studies, what you get is relatively amorphous intuitions about design and agencym, that are pretty much universal, are culturally molded into highly specific, and highly valuable religious beliefs. That's when the real problem begins: when the intuitions have been so reinforced that it is difficult to get any contrary information past their various filters.

Exceptionally interesting post - I didn't know about any of the work you mention, but I'll go find it now.

Another habit of mind that has struck me is our intuitive division of the world into active agents vs passive objects. Darwinian evolution is counter-intuitive and disturbing to many, I think, because it recasts living organisms (strictly, populations or species) as passive objects, molded by selection, rather than active agents pursuing their own destiny. Lamarckism is a much more immediately appealing idea, not just because it is transformational rather than variational, but also because it interprets evolutionary change as purposive.

Intriguingly, I think even evolutionary biologists struggle with the active/passive distinction when they try to talk about the role of behaviour in evolution. Having embraced the idea of a species as passively shaped by external selective pressures, it is then hard to come to terms with theories of niche construction, which emphasise the fact that the selection pressures a species experiences are determined by its behaviour. Of course, there is no real contradiction here, just some awkwardness in the language - but this can get in the way.

Anyway - great post, really made me think...

I realize that you are addressing only the issue of teaching evolution, but wouldn't the 3 points you make in your conclusion affect learning in most of the sciences and some mathematics.

Students come into the classroom with a variety of beliefs some of which they've developed on their own as a way of interpreting their perceptions of the world. Physics and non-Euclidian geometries, for example, could set-up situations where the student's belief structure is in conflict with the material presents.

Actually, yes, though in other sciences there might be different intuitions involved. There's a lot of research on "folk physics" and "folk mechanics," for instance, in which it has been repeatedly shown that our intuitions about the way things work, physically, don't accord with basic physics. But where evolution is concerned, people tend to focus on the cultural roadblocks to understanding and belief, so I thought I'd talk a little about the built-in difficulties.

I found your post through The Tangled Bank. Frankly, it puts my humble contribution to shame. As a physics teacher, I have to deal with a different set of preconceptions. Most teenagers by the time they arrive in my classes are confirmed Aristotelians. They are convinced heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones, that objects naturally "want" to come to rest, that appliances only use the charges they need and return the unused ones to the power company. We won't even go into their concepts of why the earth has seasons.

Evolution is a complex subject, and is especially hard to explain to someone predisposed to not accept its validity. Your post brings up not only important issues for us educators, but for science "defenders" in general. It is just easier for people to accept a Creator or designer than to accept an impersonal, random "force of nature" brought us to the point we are at now. Accepting the scientific explanation is hard work, and many students (and adults!) would rather not take the time and effort.

One thing we physics teachers learn early on is that it is essential to knock the "wrong" ideas out of students' minds before providing them the "right" ones. It cannot be done in one lesson. It takes repetition and patience on the part of the instructor. I admire bio teachers who try to bring students at least to the point of considering evolution as valid.

Great post. I'm linking to it.

Thank you for your response, Chris. You now have me wondering if some of the difficulties people have with math doesn't come from a type of "folk math" akin to the "folk physics" you mentioned. I'll have to look into this.

This really is a very interesting, and thought inspiring post. As such, I've linked to it today as suggested reading.

I agree that their are many cognitive barriers separating evolutionists from creationists (i.e. creationists are basically stupid) but I do not believe this accounts for such widespread rejection of evolution. Few people understand relativity but this does not mean they are 'anti-einsteinians' . As a general rule people happily accept what they don't understand or understand poorly on authority alone! So why can't they do the same for evolution? The answer is that people have an instinctive desire to feel 'superior' (for the sake of peer acceptance and high social status within the prehistoric tribal unit) and the theory of evolution, with it's appeal to simian ancestory and mortality, does NOT satisfy this instinct. It could be argued then that natural selection has actually equipped humans with the emotional machinery to reject the fact!

Lots of words, that amount to little more than a rehash of the old, self-serving line, according to which belief in Evolution is progressive, and disbelief, primitive...

The basics of evolution -- ie, natural selection working on randomly-produced mutations -- are simple, and even easy; even such presumably stupid people as the creationists understand them. Such presumably intellligent people as the disciples of Charles Darwin, however, clearly lack the cognitive disposition necessary to grasp the fact that paleontology, physiology and genetics, studied without a prioris, contain nothing to corroborate Charles Darwin's conjectures and speculations.

セフレ北海道セフレ宮城・セフレ青森セフレ福島セフレ秋田セフレ岩手セフレ山形セフレ新潟セフレ長野セフレ山梨セフレ東京セフレ神奈川セフレ埼玉セフレ千葉セフレ群馬セフレ茨城セフレ栃木セフレ大阪セフレ兵庫セフレ京都

I agree and enjoyed reading, I will make sure and bookmark this page and be back to follow you more.

I agree and enjoyed reading, I will make sure and bookmark this page and be back to follow you more.Thanks for your post , it is very nice and helpful . all our products are top quality and low prices . would you like something ? ok follow me ! better choice better life !

NFL Jerseys

tn chaussures

Thanks for sharing . great article . all our products are top quality and low prices .

would you like something to buy ? for example clothes and shoes . ok ! follow me !

chaussures puma

Tn Requin

Cheap Polo Shirts

better choice better life !Thanks for your post , it is very nice and helpful .

discount Chloe

newest Chloe

Chloe bags 2010

Chloe totes

bape shoes

bape clothing

discount bape shoes

cheap bape shoes

bape jackets

babyliss

Benefit GHD IV Styler

GHD IV Salon Styler

GHD Mini Styler

GHD Precious gift

GHD Rare Styler

Gold GHD IV Styler

Gray GHD IV Styler

Instyler

Kiss GHD

Pink GHD IV Styler

Pure Black GHD

Pure White GHD

Purple GHD IV Styler

wholesale ed hardy

ed hardy wholesale

discount ed hardy

Babyliss

Benefit GHD

Ed hardy streak of clothing is expanded into its wholesale ED Hardy chain so that a large number of fans and users can enjoy the cheap ED Hardy Clothes range easily with the help of numerous secured websites, actually, our discount ED Hardy Outlet. As we all know, in fact Wholesale Ed Hardy,is based on the creations of the world renowned tattoo artist Don Ed Hardy. Why Ed hardy wholesale? Well, this question is bound to strike the minds of all individuals. Many people may say cheap Prada shoes is a joke, but we can give you discount Prada Sunglasses , because we have authentic Pradas bags Outlet. Almost everyone will agree that newest Pradas Purses are some of the most beautiful designer handbags ( Pradas handbags 2010) marketed today. Now we have one new product: Prada totes. The reason is simple: fashion prohibited by ugg boots, in other words, we can say it as Cheap ugg boots or Discount ugg boots. We have two kinds of fashionable boots: classic ugg boots and ugg classic tall boots. Ankh Royalty--the Cultural Revolution. Straightens out the collar, the epaulette epaulet, the Ankh Royalty Clothing two-row buckle. Would you like to wear Ankh Royalty Clothes?Now welcome to our AnkhRoyalty Outlet. And these are different products that bear the most famous names in the world of fashion, like Ankh Royalty T-Shirt, by the way-Prada, Spyder, Moncler(Moncler jackets,or you can say Moncler coats, Moncler T-shirt, Moncler vest,and you can buy them from our discount Moncler outlet), GHD, ED Hardy, designer Sunglasses, Ankh Royalty, Twisted Heart.

AirMax BW|AirMax Huarache|AirMax LTD |AirMax Skyline |AirMax TN

AirMax Zength|AirMax 09 Sneakers|AirMax 180|AirMax 2003|AirMax 2006|AirMax 2009|AirMax 2010|AirMax 360 |AirMax 87|AirMax 90|AirMax 91|AirMax 92|AirMax 93|AirMax 95|cheap ugg boots|discount ugg boots|ugg boots|classic ugg boots|ugg classic tall boots|Dior sunglasses|Ray Ban sunglasses|Fendi Handbags|Hermes handbags|Miu miu Handbags|Timberland Boots|timberland outlet|Moncler Jackets|Moncler coats|discount Moncler Vest|Moncler outlet|moncler polo t-shirt

Post a Comment