[E]very representation of a movement awakens in some degree the actual movement which is its object.I've described the Bargh studies at length before (here), so I won't do so again, but I'll quickly summarize a couple of them. In two of the studies, researchers presented participants with a scrambled sentence task, which consists of giving them a set of words and asking them to use those words to form a sentence. In one experiment, half of the words primed the concept RUDE, and half primed the concept POLITE, while in the other experiment, one version had words associated with the concept ELDERLY, and the other words that were age-neutral. When the concept RUDE was primed, participants were quicker to interrupt an experimenter than when the concept POLITE was primed, and when the concept ELDERLY was primed, participants walked more slowly than when they had been presented with age-neutral words. So far, no one has actually tested an explanation of these interesting demonstrations, though Bargh now at least recognizes that it's time to start trying to do so. But each time I've read about these sorts of effects, I've thought about studies showing the reverse effect -- action priming thought (e.g., performing avoidance actions priming negative evaluations). So I wondered if performing stereotyped actions might prime stereotyped thinking.

Well, Thomas Mussweiler wondered that as well, but instead of resting on his laurels like me, Mussweiler actually did the research1. In his first experiment, he "unobtrusively induced" half of the participants to move in a way associated with obesity. I'll let Mussweiler describe the method for inducing this sort of movement "unobtrusively":

The first study was introduced as part of a research project conducted in collaboration with the local lifeguards. The ostensible purpose of this study was to examine how well people are able to move in emergency situations. Participants were asked to perform a number of movements designed to simulate typical movements on board a ship and in water. The instructions were carefully worded to avoid any reference to concepts associated with portliness. Experimental participants were asked to put on a life vest and a set of four gymnastic weights that were wrapped around their wrists and ankles. The experimenter explained that the weights were used to simulate water resistance. The life vest and weights unobtrusively induced participants to move in a portly manner. (p. 18)The participants then performed a series of actions, like climbing onto a chair. The other half of the participants, the control group, performed the same actions without wearing the vest or weights.

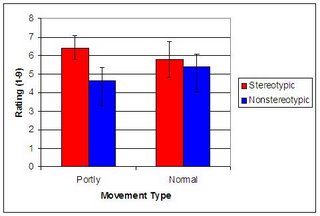

After completing the movement portion of the study, participants were told they were also going to participate in a second, unrelated study on "person perception." The study involved reading a description of a person in "ambiguous terms," and then rating the person on fifteen dimensions, seven of which were associated with obesity stereotypes (based on previous research, e.g., healthy, insecure), and eight of which were not (e.g., musical, articulate), using a nine-point scale. The results are in the pretty graph I made from Mussweiler's Table 1, below:

As you can see, the people whose movements were stereotyipically "portly" rated the person described in "ambiguous terms" higher on traits associated with the obesity stereotype than on traits not associated with that stereotype, and their ratings on the stereotypic traits were also higher than those of the control ("Normal," in the graph) participants. So it appears that performing "portly" movements primed "portly" stereotypes.

As you can see, the people whose movements were stereotyipically "portly" rated the person described in "ambiguous terms" higher on traits associated with the obesity stereotype than on traits not associated with that stereotype, and their ratings on the stereotypic traits were also higher than those of the control ("Normal," in the graph) participants. So it appears that performing "portly" movements primed "portly" stereotypes.In the second study, participants were placed on a stationary bicycle and instructed to either pedal very slowly (experimental group), or pedal at a normal speed (control group). They then read an ambiguously worded description of a person, as in the first experiment, and were asked to rate her on one stereotypic (forgetfulness) and one nonstereotypic (friendliness) dimension. Once again, participants who had performed the stereotypic action, pedalling slowly in this case, rated the person higher on the stereotypic trait than participants in the control group, though it should be noted that the ratings for the stereotypic trait (7.11 and 6.22, on a 9-point scale, for the experimental and control group respectively) were much higher than for the nonstereotypic trait (2.68 and 2.84) in both groups. And one has to wonder whether moving slowly primes only the elderly stereotype, if it primes a stereotype at all. Hell, moving slowly is associated with obesity, too. Might these participants have rated the person higher on obesity-stereotypic traits as well? Why the elderly stereotype specifically? And was the description really neutral with respect to the person's forgetfulness if both the experimental and control groups both thought the person was pretty forgetful (an average rating of 4 or 5 would mean an average level of forgetfulness, but both groups average ratings were over 6)? Unfortunately, the description isn't included in the article, so we can't judge for ourselves.

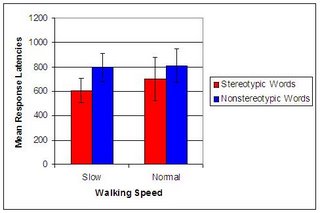

The third study was almost the exact reverse of Bargh's study. Participants were first instructed to walk in a circle for five minutes (listening to a story on headphones) at either a slow pace (30 steps per minute) or a fast one (90 steps per minute). When the five minutes were up, participants completed a lexical decision task. In lexical decision tasks, letter strings are presented, and participants are told to indicate whether the strings are words or not as fast as they can. Lexical decision tasks are often used as measures of priming. In this study, the participants were presented with 40 letter strings, eight of which were words associated with the elderly stereotype, 8 of which were words not associated with the elderly stereotype, and 24 of which were nonwords. Participants who walked slowly responded to elderly-stereotypic words significantly faster than did participants who walked at a normal speed, once again indicating priming of the elderly stereotype. The data are in the graph below (created by yours truly from Mussweiler's Table 3; latencies are in milliseconds).

So, here we have three demonstrations, using two different stereotypes and two different measures of priming, that the effects Bargh and his colleagues have observed in actions after priming stereotypical thoughts can also be observed in reverse, by having people perform stereotypical actions and thereby priming stereotypical thoughts. At least, that's the standard interpretation. As I indicated in my reaction to Mussweiler's second experiment, I'm somewhat skeptical of this interpretation. It's clear that priming is occurring, but what, exactly, is doing the priming (the movement, the level of arousal, or what)? And what's being primed (single stereotypes, multiple stereotypes, whole stereotypes or just parts, etc., etc.)? As with the Bargh studies, no explanations are actually tested in Mussweiler's studies, so we don't really know the answer to any of the questions raised by the demonstrations. But it does seem to provide another piece of evidence for the tight coupling of action and thought that James mentioned over 100 years ago, as well as for the largely unconscious nature of that coupling. If nothing else, then, these studies provide yet more evidence for my belief that you can find everything we've learned in modern cognitive science in James' writing.

1Mussweiler, T. (2006). Doing is for thinking! Stereotype activation by stereotypic movements. Psychological Science, 17(1), 17-21.

6 comments:

In your first quote, I think you double pasted, because it repeats itself half way through.

Oops, thanks. I'll fix that.

Hmm. I suspect that ethnic stereotypes would, however, be only unidirectional? Like THAT proposal would pass an IRB.

purzycki, the link in the sentence right after the James quote discusses some of Bargh's work using ethnic stereotypes.

Ah yes, thanks. I was thinking more along the lines of a study conducted much closer methodologically to the present breakdown. Such as *unobtrusively inducing* subjects to act like dogmatic control-freaks to see whether or not they reacted quicker to the word CAUCASIAN (or some other such behavior/race relationship) and vice versa. Obviously this example is half in jest, but it looks like an even finer line in this case potentially.

I imagine you could do the reverse of the Bargh study in the linked post. Have people act hostilely, maybe. I don't know how you "unobtrusively induce" people to act hostilely, though.

Post a Comment