An entrée of Cognitive Science with an occasional side of whatever the hell else I want to talk about.

Thursday, December 30, 2004

Upcoming Posts

Religion, Morality, and Posner

- The peyote case—an Indian tribe uses peyote in its religious ceremonies; the state outlaws peyote.

- The Amish case—the Amish don’t want their kids to attend high school, in violation of the state’s compulsory schooling law.

- The Ten Commandments case—is it lawful to post the Ten Commandments in a courthouse or other public building?

- May a state ban the teaching of evolution, or require teaching of “creation science,” in its public schools.

- Should the fact that most opposition to abortion is based on belief in ensoulment invalidate laws restricting abortion on demand?

- Should the fact that much of the opposition to gay marriage rests on religious belief invalidate laws refusing to recognize such marriages?

In the first two cases, religion is seeking an exemption from secularly motivated laws of general applicability. In the next pair of cases, the state is being asked to enact, in effect, a religious dogma. The last two cases are the interesting ones. A law prohibiting abortion or gay marriage is not an enactment of religion in the same sense as posting the Ten Commandments or teaching divine creation, because those prohibitions do not mention religion or contain a religious message; they are merely inspired by religion. It would be a leap to regard them as “establishing” religion. And, in my view, a leap too far.I think Posner's view of 5 and 6 is an oversimplification, and not simply because his description of it is so short. I think the difference between cases 3 and 4 and cases 5 and 6 is much more difficult to define. I think the fact that the primary (and perhaps the only sound) justifications for outlawing abortion and gay marriage are religious means that, in effect, such laws do contain a religious message. That the religious message is not made explicit in the wording of the relevant laws does not mean it is not there. If the religious message defines the laws, then whether or not we acknowledge this in the wording is irrelevant. In a sense then, and contrary to Posner's assertion, such laws do amount to the establishment of religion.

The leap would imply that the only morality that should guide public policy in today’s United States is a secular morality.

To see why I think this is the case, let's look again at the other case I used in my original post: laws requiring that women wear burkhas. I suspect that if such laws were passed, Posner and many others would argue that they amounted to the establishment of religion, because the wearing of burkhas is prescribed entirely on religious grounds. Yet, if we adopted Posner's justification for his views on the abortion and gay marriage cases, we would have to accept that, if Muslims constituted a majority of American voters, it would be constitutionally permissable for them to vote for laws that required women to wear burkhas. Here is Posner's statement justifying his view:

If morality, or at least a large part of the moral domain, lives below reason as it were, isn’t the practical consequence that morality is simply dominant public opinion? And so if the population is religious, religion will influence morality, which in turn will influence law, subject to constitutional limitations narrowly interpreted to protect the handful of rights that ought not to be at the mercy of the majority.If, under this view, the majority of Americans were Muslim, and held strict Islamic views of sexual morality and gender, then there religion would and should influence law. Yet I think most of us, even those Christians who feel that abortion and gay marriage should be outlawed for strictly religious reasons, are likely to feel that if non-Muslim women are forced to wear burkhas based on the moral views of a religion to which they do not adhere, this would amount to government endoresement of a particular religion. The constitutional limitations that Posner mentions are designed to protect individual religious (and non-religious) liberties from the majority's religious beliefs. Why, if they should protect us against the Muslim belief that women should wear burkhas in public, should they not protect us from the Christian and Jewish belief that abortion is murder because we are endowed with souls from conception, or the belief that gay marriage should be outlawed because homosexuality is strictly prohibited in Christian and Jewish scriptures (under some interpretations)? Do not these laws also restrict the liberties of those who do not share these religious beliefs?

One potential way around this is to argue that there are, in fact, secular moral reasons for outlawing abortion and gay marriage (or forcing women to wear burkhas). This is the argument that Jeremy Pierce made in some good comments to my previous post. Is it in fact the case that there are non-religious moral reasons for opposing abortion and gay marriage? There have been some non-religious arguments offered against both, but two problems arise when we consider them. Does this mean that outlawing them is not, in fact, the establishment of religion? I don't think it's so straightforward. Putting aside for a moment that I have yet to hear any valid or sound arguments against either that are based entirely on non-religious premises, the existence of such arguments, perhaps even under Posner's view, is insufficient to demonstrate that the laws have not been enacted for religious reasons. For the majority of Americans who oppose gay marriage or abortion, their primary moral reasons for doing so are in fact religious (even the arguments criticized in the pro-choice essay cited by Jeremy are all religious ones, put forward primarily by the Catholic church), and thus their influence on public policy still amounts to the legal adoption of a particular religious view.

Now that I've gotten all that out of the way, I should say that I think even my view is an oversimplification, though one that is less internally inconsistent than Posner's. As I said in the previous post, voting one's values, or morality, or conscience, really just means voting for particular reasons, be they religious or secular. The point I'm ultimately trying to get across is that I feel completely justified in criticizing anti-choice and anti-gay voters for voting on religious grounds. However, I also don't think it's practical to attempt to prevent them from doing so. My only real hope is that such criticisms will be allowed, and taken seriously, in the public debates over these issues, and that lawmakers will take into consideration the religious nature of such laws.

Philosophers' Carnival VII: The Holiday Edition

Hello, and welcome to the 7th Philosophers' Carnival. We are sorry for the delay, but the holidays, and if I were to guess, the end of the semester (for many of us) led to a shortage of submissions. However, we now have several great posts for your reading pleasure. They range from a look at Hume's analysis of analogy to a discussion of cutting edge theory of truth. If you're looing for good philosophical discussions in the blogosphere, then look no further.

Before we get started, we should all give a nod of appreciation to Richard. He keeps the Carnival rolling pretty much on his own. Without him, there would be no Philosophers' Carnival. So, if you enjoy these regular collections of quality philosophical posts, then you should let him know. If you don't enjoy them, well, what are you doing here?

Now, back to business. It seems appropriate to start with the historical because, well, that's where things start. From there, we'll journey around the world of blog philosophy, and hopefully at the end of the trip, each of us will have found something that piques our interest, raises interesting questions, or forces us to see things in a new way. That's what philosophy is for, right? In case you don't want to read through all the summaries, at the end, you will find each of the links without descriptions. Enjoy.

We have two history of philosophy posts, one on Hume and one on Ockham's Razor. We'll start with Hume

On the Humean Analysis of Analogy

At Siris, we have this wonderful look at Hume's view of analogy.

Tucked away at the very end of Treatise 1.3.12 we find Hume's analysis of analogy.This analysis is concerned with Hume's treatment of philosophical probability, as Brandon notes:

Philosophical probability for Hume consists essentially in imperfect causal reasoning; it is distinguished from causal proof, which occurs when we are dealing with something that happens in exactly the same way with perfect regularity. Obviously, there are many cases in which we don't have such ideal conditions to go on, and this is where philosophical probability comes in. In philosophical probability, either the resemblance or the regularity (constancy of the conjunction of events) are imperfect. This brings us to the Humean analysis of analogy.Brandon then uses three "pregnant" sentences from the treatise to launch his discussion:

1. In those probabilities of chance and causes above-explain'd, 'tis the constancy of the union, which is diminish'd; and in the probability deriv'd from analogy, 'tis the resemblance only, which is affected.

2. Without some degree of resemblance, as well as union, 'tis impossible there can be any reasoning: but as this resemblance admits of many different degrees, the reasoning becomes proportionably more or less firm and certain.

3. An experiment loses of its force, when transferr'd to instances, which are not exactly resembling; tho' 'tis evident it may still retain as much as may be the foundation of probability, as long as there is any resemblance remaining.

Ockham's Razor

You probably think you know Ockham's Razor, but you're likely to learn something new about it in this excellent post from Studi Galileiani. For instance, did you know that the principle commonly stated as

Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem (“Entities are not to be multiplied beyond necessity”).is not explicitly stated in the writings of Ockham himself? I didn't. Hugo writes:

Although referred to as Ockham’s Razor after William of Ockham, a Franciscan living at the turn of the fourteenth century, this version has not be found in any of his extant works. The closest match (Frustra fit per plura quod potest fieri per pauciora or “It is pointless to do with more what can be done with fewer”) may have been written in quoting others, and indeed the general principle was common among Aristotelians. In brief, the advice is that we should not invoke entities in explaining a phenomenon or developing a theory that are not necessary to do so.

In addition to this interesting piece of trivia, Hugo writes on "the principle, its domain of application and some associated philosophical concerns, using examples from the history of science to illustrate some of the points at issue."

From history, we move on to ethics, policis, and religion, on which we have some great posts.

God the Utilitarian?

Is God a utilitarian? Well, perhaps he should be.David Hunter of Prosblogion writes:

Most of us are aware of the argument from evil and the various wranglings associated with it for example the debates about whether God could create free willed beings who would always chose to do the good. These debates are typically metaphysical debates about theodicies. Theodicies however are less commonly challenged on ethical grounds, to give one example it is rare for proponents of the argument from evil to respond to the free will theodicy (roughly the claim that the existence of evil is justified because it is a necessary consequence of having free will which is a great good) with the claim that free will doesnt really have great value.

I want to suggest that actually moral issues and particularly the moral presuppositions of theodicies need to be investigated further. For example I argue that many theodicies will only succeed if something like consequentialism/utilitarianism is true.

Act vs. Rule

It may not be the case, however, that something like consequentialism/utilitarianism is true. Most of you are probably familiar with the common objections to utilitarianism. In a very nice post at Orange Philosophy on one of the common utilitarian responses, which reads:

It's not about what acts in particular lead to the best consequences in terms of happiness and unhappiness (or substitute your own intrinsic goods if you want to expand this to a more general consequentialism). The original theory put it that way, but what we really ought to do is look at which types of act will tend to produce good results.Jeremy Pierce argues that the "act/rule distinction often used to protect ethical theories from standard objections is a complete mistake." He writes:

I have two problems with this. First, it seems to do as much damage as it saves. Second, it isn't at all clear what this is supposed to look like, because rules turn out to operate on a continuum from very specific rules to more general rules. It causes as much damage at is saves for the very reasons that utilitarianism is supposed to do better than theories like Kant's when Kant's absolutism seems wrongheaded.

In Defense of Almeida and Oppy

Back to discussions of God, free will, the problem of evil, and morality, Clayton Littlejohn considers whether there are goods that justify God's lack of intervention. In a recent paper, Almeida and Oppy have argued that

if there were goods that justified God's refraining from intervening, there should be goods that would justify our refraining. As there are no such goods, there is no justification for God's refraining and the argument from evil is up and running.Littlejohn defends this argument against objections made by Trakakis and Nagasawa, which he summarizes with the following:

[I]n virtue of his role, there are role-relative goods that justify God refraining that wouldn't justify our refraining.Littlejohn ultimately concludes that

The upshot is that at best, T and N leave the theist unable to square their theism with the claim that God is benevolent. That leaves them in bad shape, what with theism entailing that God is benevolent.To see how he gets to that conclusion, read the post. It's well worth it.

Determinism and Disneyland

Are determinism and free will compatible? This is one of the most hotly debated topics in philosophy today, and while some have used the Frankfurt examples to attempt to solve the problem, Neal Tognazzini tells us at The Garden of Forking Paths that we would do better to look to Disneyland examples. He writes:

Determinism, I think, is less like a Frankfurt-style counterexample and more like Disneyland. Let me explain.

You know that Disneyland ride where you get into a car that's fixed to a track and then you ride around on the car? Well, every time I go there I always have to fight to get the seat with the steering wheel. (We all want to be the driver, don't we?) And occasionally I succeed, and I get to pretend like I'm driving the car. Of course, I'm not actually driving the car, and I realize this.

But now suppose that I don't know that the car is on a track, and in fact I think that I am controlling the car. I turn the steering wheel to the right when I come to a turn, and (what do you know?) the car goes to the right. I have no idea that I didn't have any effect on the direction that the car turned. It seems to me that this is what determinism would be like, if it were true.

Is this picture of determinism compatible with free will? Neal thinks not. Read the post to see why.

"Drebenized"

Burton Dreben is known for believing

Philosophy is garbage. But the history of garbage is scholarship.Or

Nonsense is nonsense, but the history of nonsense is scholarship.In response, John Rawls writes:

The crucial questions in understanding Burt's view are: What is philosophical understanding? What is it the understanding of? How does understanding differ from having a theory? I wonder how I can give answers to these questions in my work in moral and political philosophy, whose aims Burt encourages and supports. Sometimes Burt indicates that my normative moral and political inquiries do not belong to philosophy proper. Yet this raises the question. Why not? And what counts as philosophy?Brian Leiter (who is responsible, indirectly, for the square quotes around the word "analytic," by the way) wonders what philosophers think about this. Read the whole post, and let him know in a comment.

Realistic Utopia, a fantasy?

For more on Rawls, we turn to Joe of Oohlah's Blog-space. He writes:

Some may object to Rawls's idea of a reasonably just constitutional democratic society by insisting that this type of society is purely fantasy. Dreadfully evil events, like the Holocaust and the Inquisition for instance, prove that the hopes expressed by Rawls's realistic utopia are fantastic.Joe doesn't think that Rawls' responses to these objections work. Do you agree? Read the post and decide.

Equality of Opportunity One and Two

There is a distinction between "equality of opportunity" and "equality of outcome," and in the first of two posts at the popular new blog Left2Right, Don Herzog writes:

Equality of opportunity is great; equality of outcome -- somehow trying to ensure that everyone crosses the finish line together, or that everyone earn $28,967 a year, live in an 1100-square-foot apartment, and have 2.28 children -- is wildly unjust and tyrannical.

But how do we ensure equality of opportunity without moving toward the tyranny of equality of outcome? This is the question Herzog addresses in these two posts. He notes that

It's not enough to stop handicapping some runners and privileging others. Equality of opportunity seems to depend on some version of equality of starting points.but

Equality of starting points can't literally mean identity of starting points, for the same reason that equality of outcomes is repulsive. No one in his right mind should want to homogenize schools, communities, and the like, and anyway it's impossible. So in the usual story line, which I'm mechanically following -- and which you are obviously free to challenge -- the best interpretation of equality of starting points is setting some decent minimum or floor below which no one may fall. There's endless room for disputes in various domains about where that floor is. But I'll 'fess up: it seems to me we're not meeting it.In the second post, we get a closer look at where Herzog feels this floor lies, and how he thinks we should meet it, starting with the extension of "antidiscrimmination norms." In the process of sketching his own view, he defends it against some libertarian objections. Once again, this is a post that should spark a lot of thought and discussion, so go read and discuss it.

Lexicographic Lapses

Starting from a quote

Lexicographic orderings crumble in the face of scarcity.Glen Whitman of Agoraphilia writes about ethics, law, and political economy. The point of the quote, he writes, is that

Lexicographic value or preference orderings may seem sensible in the face of small trade-offs, but they become highly implausible in the face of large ones.

Whitman believes that this fact has implications for a broad range of philosophical problems and views. For instance, in response to a common example used in arguments against utilitarianism, he writes:

The insistence that you should never kill an innocent, regardless of the consequences, amounts to a lexicographic preference that places first priority on the number of people you kill, and only second priority on the number of people who get killed by others.

He offers similar responses to cases of "lexicographic preference" in property law, and the ordering of rights.

Flourishing

Considering the following view of wellfare:

DF: A person is well-off to the extent that their desires are fulfilled.Richard of Philosophy, etcetera considers several objections to the view that DF, which stands for Desire Fulfillment, provides an adequate account of human flourishing. After attempting to address each of these objections, Richard writes:

I'm attracted to the theoretical simplicity of DF, but concerned that it may prove too simple to do justice to our wide range of intuitions about welfare and human flourishing. However, the general 'desire fulfillment' approach is very flexible, so I think most of the challenges can be successfully met by modifying or clarifying aspects of the theory, as I attempted to do in my responses above. (I'd be very curious to hear how convincing others found these objections and my responses.) But of course too many complications would negate the original appeal of the theory. Perhaps my desire for an elegantly simple theory of welfare is not one that can be fulfilled?What do you think? Can DF work? Does it need some supplementary propositions? Read Richard's post, and let him know what you think.

Ethics and Neurology

In the last post on ethics, religion, or politics (last not for any reasons related to its quality, as each of the posts is of a high quality, but because it provides a nice lead-in to the next series of posts), Brian Weatherson writes at Thoughts, Arguments, and Rants that when relying on intuitions to do ethics, the sorts of scenarios you consider are important. In particular, life-and-death situations might yield intuitions that are incompatible with those we derive from more ordinary situations. What does neurology (or neuroscience) have to do with this? Brian writes:

Bracketing the details of the cases for now, it’s worthwhile to stop back and reflect on what this should tell us about methodology. In particular, I want to think about what would happen if we found out the following things were true.As you might imagine, and as Brian notes, the third of these is a bit of an oversimplification. Still, he uses it to make the point that we may need to adjust our methodologies when doing ethics if different types of scenarios produce neurological responses that differ in theoretically-relevant ways.

* Systematising intuitions about life-and-death cases supported moral theory X

* Systematising intuitions about everyday cases supported moral theory Y, which is inconsistent with X

* The reason for the divergence is that different parts of the brain are involved with forming moral intuitions about everyday cases as compared to life-and-death cases; everyday cases are handled by a part of the brain generally associated with cognition, life-and-death cases by a part of the brain generally associated with emotional response.

From ethics and related topics, we move on to epistemology, where we find three excellent posts on relatively different topics. Let's start with naturalized epistemology.

Epistemology embodied

Brian Weatherson's post raises the question of the importance of empirical evidence in epistemological methodologies in ethics. At Majikthise, Lindsay Beyerstein addresses the same question for epistemology in general.

Some traditionalists argue that empirical data are at best peripherally relevant to epistemology. They acknowledge that specific claims to knowledge are dependent, as a contingent matter of fact, on the reliability of the psychological processes that generate and sustain them, but they maintain that these details are relatively unimportant to epistemology.Lindsay explicitly states something that Brian's post hints:

Traditionalists argue that the real philosophical action takes place at the conceptual level. They argue that we must understand concepts like "knowledge" and "justification" by consulting our intuitions about the conditions for the proper applications of these concepts. The critical tests are thought experiments with N's of 1. Philosophers reflect on paradigm cases and attempt to recognize the factors that, say, differentiate knowledge from mere true belief. Then they test out their conditions by trying to formulate counterexamples in which the proposed criteria are met but the concept can't be applied.

This kind of philosophical methodology makes a lot of empirical assumptions about human cognitive capacities of the philosophers undertaking the analysis. We take ourselves to be analyzing the ordinary concept of knowledge.Lindsay argues that recent data from experimental philosophy research call this assumption into question. Instead of using these traditional methods, we should adopt a naturalized approach to epistemology, ala Quine. She concludes:

From cognitive psychology we learn more about how human beings, ourselves included, learn and reason. By observing scientific practice and reflecting on scientific methodology, we observe the expansion of empirical knowledge. When we reflect on questions of justification, we must do so in light of our understanding of ourselves as limited, embodied beings. The validity of our methods depends on our ability to rule out or compensate for certain limitations or distortions imposed by our own cognitive makeup.As a cognitive psychologist, I couldn't agree more! But you may disagree. Read the post to see her complete argument, and decide for yourself.

Alethic Functionalism

Mike of Desert Landscapes gives us a look at a new theory of truth, alethic functionalism. He writes:

Michael Lynch has recently argued for a new and interesting theory of truth, Alethic Functionalism. Alethic Functionalism holds that truth is a multiply realized property. It is an inflationary account and seems to combine positive features of both pluralistic and monist theories.

He contrasts this new theory with traditional correspondence and coherentist theories, listing the advantages of this new theory over the old. I would offer more of a summary, but the post relies heavily on an analysis of several propositions, and I'm simply not bright enough to summarize it without detailing them all. So, to learn about this interesting new theory, you will have to read the whole post yourself.

The Value of Knowledge and Being in a Position to Know

Is there a difference between the value of knowledge and mere true belief? Jon Kvanvig addresses one answer to this question in a post at Certain Doubts. The position is as follows:

Suppose S knows that p and S’ only believes truly that p. S is thereby in a position to know things that S’ is not in a position to know. The proposal is that this difference explains the difference in value between knowledge and (mere) true belief.Jon raises the following concern with this position:

Take the range of claims you’re in a position to know in virtue of knowing p. Suppose that you know all of these truths. Then compare knowing all of these truths with only believing them and being right.

Jon claims that the proposal only works if the range of claims is non-insular, i.e.

[C]oming to know something that one is in a position to know may enlarge the class of things one is then in a position to know.

Finally, we have one post on the teaching of philosophy.

End of semester wrap-up

Adam Potthast of Metatome wants philosophy instructors to discuss what worked, and what didn't, in the courses they taught this semester. He offers his own experience, and invites you to do the same. In my mind, this is one of the best ways for academics to use the blogosphere.

So, there you have it, the 7th Carnival. As promised, I'll end with the links to each of the posts above, without summaries. However, before I do that, I want to make one more editorial comment. To this point, the Carnivals have been getting very good posts from amateurs and professionals alike, but there is something lacking. While Brandon of Siris has given us consistently good posts on the history of philosophy, almost all of the other submissions have come from within what I will call, for lack of a better label, the "analytic" tradition. I think, and I'm sure others, even many of those who prefer analytic philosophy, would agree, that the lack of submissions from areas of philosophy that have traditionally been considered "continental" or "historical" is unfortunate. I hope that some of you out there who have good posts from these areas, or know people who do, submit or nominate them for the next Carnival. As for everyone who has been submitting, keep doing so. Hopefully as the Carnival grows, we'll get great analytic posts, as we have to this point, and great historical and continental posts as well.

There's something else lacking that may be even more problematic, and symptomatic of larger trends in the blogosophere. In this, the 7th Carnival, there is only 1 post by a female blogger, and it was nominated rather than submitted by the blogger herself. This ratio is reflected in the previous Carnivals as well. I'm afraid that this sort of thing only furthers the commonly-held (even among many philosophers) and viciously false belief that philosophy is a man's game. I wish I had a suggestion for encouraging more female bloggers to submit, but I don't. I hope that all of you who know female philosophy bloggers will encourage them to submit posts to future Carnivals, and if they don't submit them on their own, then you might consider nominating their best posts anyway.

The Carnival Links

On the Humean Analyis of Analogy

Ockham's Razor

God the Utilitarian?

Act vs. Rule

In Defense of Almeida and Oppy

Determinism and Disneyland

"Drebenized"

Realistic Utopia, a fantasy?

Equality of Opportunity: One and Two

Lexicographic Lapses

Flourishing

Ethics and Neurology

Epistemology embodied

Alethic Functionalism

The Value of Knowledge and Being in a Position to Know

End of Semester Wrap-up

UPDATE: Two very late additions:

Richard Posner, guest blogging at Leiter Reports has two very good posts on religion and law, the first here, and the second replying to comments on that post, here. In addition to the comments on Leiter's site, John Mandle has provided an excellent commentary at Crooked Timber. Given the quality of these posts, we would be remiss if we did not include them in this edition of the Carnival.

What, If Anything, Can Evolutionary Stories Tell Us About Human Cognition?

First, let's look at what evolutionary psychologists think evolutionary psychology brings to the table. Here's the opening to Leda Cosmides and John Tooby's primer on evolutionary psychology

The goal of research in evolutionary psychology is to discover and understand the design of the human mind. Evolutionary psychology is an approach to psychology, in which knowledge and principles from evolutionary biology are put to use in research on the structure of the human mind. It is not an area of study, like vision, reasoning, or social behavior. It is a way of thinking about psychology that can be applied to any topic within it. [original emphasis]In other words, evolutionary psychology is a paradigm that will allow us to understand the mind. Moreover, it is a paradigm designed to replace the naive paradigm that has dominated the psychological sciences since the days of William James. The paradigm approaches problems of the mind with 5 principles, which Cosmides and Tooby claim come from biology:

Principle 1. The brain is a physical system. It functions as a computer. Its circuits are designed to generate behavior that is appropriate to your environmental circumstances.

Principle 2. Our neural circuits were designed by natural selection to solve problems that our ancestors faced during our species' evolutionary history.

Principle 3. Consciousness is just the tip of the iceberg; most of what goes on in your mind is hidden from you. As a result, your conscious experience can mislead you into thinking that our circuitry is simpler that it really is. Most problems that you experience as easy to solve are very difficult to solve -- they require very complicated neural circuitry.

Principle 4. Different neural circuits are specialized for solving different adaptive problems.

Principle 5. Our modern skulls house a stone age mind.

Even putting aside any disagreements I might have with any of these principles, there's something odd about listing them as the principles of evolutionary psychology. What's strange about it is that, at least since the beginning of the cognitive revolution, each of these principles has been accepted by many, if not all cognitive scientists. There's something slightly disingenuous about listing them as the principles that define a new paradigm, then. A more accurate description of this new paradigm would be that it accepts the same principles that other cognitive scientists do, but places more emphasis on some principles than the accepted paradigm has. In particularly, it places more emphasis on principles 2 and 5. In practice, this has also led to a different interpretation of 4, but we'll get to that later.

Our questions about the usefuleness of evolutionary psychology, and why, with its popular success, most experts haven't bought into it, can be rephrased as questions about the usefuleness of increased emphasis on principles 2 and 5, and why so few experts have accepted this increase. So, we should start with why evolutionary psychologists believe that emphasizing 2 and 5 is important, and after that, we might begin to understand why the rest of psychology doesn't share their belief.

The most common explanation for the usefuleness of an emphasis on 2 (given by Cosmides and Tooby, as well as other prominent evolutionary psychologists like Pinker and Buss) is that understanding the conditions under which human cognitive capacities evolved will help us to understand their functions, which will in turn help us to understand the capacities themselves. Cosmides and Tooby write:

Realizing that the function of the brain is information-processing has allowed cognitive scientists to resolve (at least one version of) the mind/body problem. For cognitive scientists, brain and mind are terms that refer to the same system, which can be described in two complementary ways -- either in terms of its physical properties (the brain), or in terms of its information-processing operation (the mind). The physical organization of the brain evolved because that physical organization brought about certain information-processing relationships -- ones that were adaptive.This is, in fact, an excellent example of how understanding the function of cognition helped us to understand it. This understanding of function is, in fact, the paradigm shift that brought about the cognitive revolution. It helped us to go beyond simple associationist conceptions of behavior, and has led to the bulk of what we have learned about human cognition over the last 50 years. But once again, I'm afraid that Cosmides and Tooby are being a bit sneaky. They imply that the foundational insight of the cognitive revolution was brought about through evolutionary considerations. In fact, if you read the papers that launched the cognitive revolution, you will find few if any references to evolution or adaptation. Consider, for instance, Alan Turing's famous paper from 1950 titled "Computing Machinery and Intelligence." In it, you will find some references to evolution, but not as a producer of the information-processing brain. Instead, evolution is used as an analogy. Here's what Turing writes:

So, even though evolution had little to do with the adoption of the information-processing paradigm, it may serve as an argument for the utility of evolutionary psychology by showing that knowledge of functions is important, if evolutionary psychology can show that it provides knowledge of functions that we wouldn't have gained without evolutionary considerations. This would justify the emphasis on principle 5, which in turn requires principle 2 to work (if the contemporary cognitive system is not the ancient one, then evolutionary considerations won't do us any good), so we have an argument for an increased emphasis on both.

We have thus divided our problem into two parts. The child-programme and the education process. These two remain very closely connected. We cannot expect to find a good child-machine at the first attempt. One must experiment with teaching one such machine and see how well it learns. One can then try another and see if it is better or worse. There is an obvious connection between this process and evolution, by the identifications

Structure of the child machine = Hereditary material

Changes of the child machine = Mutations

Natural selection = Judgment of the experimenter

One may hope, however, that this process will be more expeditious than evolution. The survival of the fittest is a slow method for measuring advantages. The experimenter, by the exercise of intelligence, should be able to speed it up. Equally important is the fact that he is not restricted to random mutations. If he can trace a cause for some weakness he can probably think of the kind of mutation which will improve it.

Are there examples of such knowledge gained from evolutionary psychology? Tooby and Cosmides would suggest that their social exchange theory has provided just such knowledge about one type of reasoning. In case you don't know, social exchange theory posits that exchange is ubiquitous in social interactions, and we have an adaptive interest in determining whether those with whom we are exchanging are cheating. We have therefore evolved a cheater-detection module. This module explains our performance on social exchange versions of the Wason selection task, they argue. Thus, the evolutionary perspective has provided us with knowledge of function, and knowledge of function has helped us to understand particular behaviors, in this case, particular types of reasoning. Is this theory correct, and if so, could we have arrived at it without considering our evolutionary history? The answer to the first question is almost certainly no (see here and here). This makes the second question unnecessary, but just in case, we should try to answer it anyway. Clearly, the evolutionary perspective aided Tooby and Cosmides in the generation of hypotheses and experiments designed to test them. There are other perspectives that might have yielded the same hypotheses, however. Tooby and Cosmides are fond of comparing their theory to theories in economics. This is because their evolutionary story is largely a reworded economic one. An economic theory, therefore, might have yielded similar hypotheses.

But back to the fact that Tooby and Cosmides' theory is probably wrong. What if, instead of adopting a theory of the function of a particular cognitive capacity beforehand, based on evolutionary considerations, the two researchers had instead explored the contemporary cognitive data, and developed a theory of function out of this? If they had, they would have learned quite early on that there are several factors unrelated to social exchange that improve performance in the Wason task. There theory would therefore have been more viable. Now we start to see why cognitive psychologists, by and large, are not evolutionary psychologists, but more on that will have to wait. We should still look at the different understanding of principle 4 that we get from evolutionary psychology.

Principle 4 is essentially the principle of modularity. It says that there brain areas are specialized to perform particular functions. Under the evolutionary view, this means something else on top of this. It means that particular modules were developed through evolution to perform their specific functions. Examples of widely acknowledged modules include the visual system (which contains various sub-modules designed to perform particular visual tasks, ranging from color vision and edge-detection to object recognition), the motor system, and other pre-cortical systems. We may even have a model designed specifically to recognize faces, though the jury is still out on that one. The cheater-detection module is an example of a frontal brain area (or system) that may have evolved to perform a specific function, in this case detecting cheaters. There is even some (sketchy) neuroscientific evidence indicating that particular cortical regions are active during cheater-detection tasks but not in similarly-structured but unrelated tasks. However, while the modularity of certain pre-frontal regions, mostly associated with lower level perceptual, motor, or regulatory tasks, is well established, frontal lobe modularity is not. Furthermore, the frontal lobe modularity that has been theorized in neuroscience need not be evolved. Many of them may develop ontogenetically. In fact, at this point, it's not clear that we are going to discover many brain region-higher-order cognitive capacity associations that are generalizable across individuals. It may be that much of the organization of the frontal lobe is due largely to experience, rather than evolution. If this is the case, then the evolutionary psychological understanding of modularity may be misguided for just those cognitive capacities that it is designed to explain.

So, we now have two reasons for doubting the utility of evolutionary reasoning for understanding cognition. The first is that experience and the scientific method tell us that, at least in most cases, we will develop better hypotheses by considering data from modern human subjects, rather than their evolutionary history. This is not to say that evolution should not be used to constrain the range of possible hypotheses, but it does mean that evolutionary considerations are not likely to provide much more than theoretical boundaries. Furthermore, as our neuroscientific knowledge of higher-order cognitive capacities becomes more sophisticated, it may replace evolutionary considerations in their role as boundary providers. The second is that the evolutionary paradigm requires a strong, massive, and hard-wired modularity in the brain areas responsible for higher-order cognitive functions, and this sort of modularity may not be the way cortical regions work, and what modularity does exist may be ontogenetically designed, rather than phylogenetically. In fact, to the extent that data supports domain-general views of various higher-order cognitive capacities, the evolutionary psychological view of modularity is demonstrably false.

To sum up, most cognitive psychologists seem to feel that evolutionary considerations provide little insight into the mind. The best way to gain an understanding of cognition is to run experiments on modern subjects, and use the resulting data to form hypotheses. At most, evolutionary stories can tell us why human cognition works the way it does, but we don't need them to tell us how it works. To the extent that evolutionary stories have provided how exlanations, rather than why explanations, they have been either wrong or merely repeated what we already knew.

Wednesday, December 29, 2004

Tsunami

Monday, December 27, 2004

Carnival Delayed

Friday, December 24, 2004

Is America a Christian Nation?

Christian Nation – The Republican Party of Texas affirms that the United States of America is a Christian nation, and the public acknowledgement of God is undeniable in our history. Our nation was founded on fundamental Judeo-Christian principles based on the Holy Bible. The Party affirms freedom of religion, and rejects efforts of courts and secular activists who seek to remove and deny such a rich heritage from our public lives.She writes:

The values of the constitution are consistent with many of the values of Christianity, but also with the values of many other religions and many secular ethics. The critical point is that the constitution does not appeal to Christian doctrine to justify authority. I.e., the authority of the constitution does not rest upon tenets of faith, revealed truth, or the dogma of any particular religion... If we want to talk about the intellectual heritage of the Framers, we also have to acknowledge their debt to the secularism of the Enlightenment, to deism, to the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution, and so on.Finally, one more quote that I agree with, this one from Left2Right:

I think it contemptible to teach American history and pretend Christianity has made no difference, though I also think some people overplay or misunderstand the differences it has made.I think this is a nice response to the passage from the platform as well. If the platform means that Christian "principles," in a very broad sense, played a heavy role in determining the social and political atmosphere in which the Constitution was conceived, then it is stating something that should not be overlooked in any historical study of the United States. However, the mention of the "Holy Bible" might confuse many students of that history. Nowhere in the Bible will one find passages that lead directly to the wording of the U.S. Constitution. This is, I think, a case of overplaying or misunderstanding the difference Christianity has made in American history. It's a common error, and probably little more than an instance of history being written by the victors. Still, I think it's a potentially important error, because if the founding principles of our nation are seen as deriving exclusively from Christianity, or as being inconsistent or independent of the principles of other religious and secular systems of belief, then we have a problem. Christianity seen as an influence, even a heavy one, is not a threat to individual liberty, but Christianity seen as the traditional, and therefore rightful source of law and liberty, can be. In this latter case, Christian principles no longer influence government simply because they are the principles of the majority, and therefore still subject to the limits the Constitution places on majority rule, but instead may be seen as above those limits, because they are conceptually prior or foundational to the document that places limits. In other words, by being the religion of the Constitution and the nation itself, rather than the majority of its citizens, Christianity becomes a risk, rather than a guaranteur, of individual liberty.

Thursday, December 23, 2004

Voting One's Values

In his comment, Jeremy Pierce, aka Parableman, used a phrase that I've heard often from evangelicals: "vote their conscience." You could substitute this with "vote according to their values," and mean pretty much the same thing, so that's how I'm going to talk about it from this point on. More often than not, this sort of phrase is used in a fashion similar to the following:

Evangelicals should vote according to their values, and should not be faulted for doing so.The first time I heard a statement like this one, my initial reaction was one of complete agreement. Obviously, in a democracy, people should vote how they want to, and more often than not, they will want to vote according to their values. But then I started to think about it. Can people always vote according to their values? Might their be some circumstances in which doing so will lead to contradictions? In particular, are there not some groups of values that, as guides of personal behavior, are perfectly consistent, but, when they determine public policy decisions, can contradict each other? If this is the case, then people should not always vote according to their all of their values, and when they vote according to some values, they should be faulted for doing so.

To make this all more clear, consider an example of a value that is shared by many, if not most Americans, regardless of religion. I think it is safe to say that most of us place a great deal of value on our religious freedom. Furthermore, I think the concept of religious freedom that most Americans hold contains two components, either explicitly or implicitly. The first component, call it the positive component, holds that we should have the freedom to practice the religion that we choose, in the way that we choose (within reason, of course). The second component, call it the negative component, holds that we should not be forced by law to practice any part of other peoples' religions. The positive component simply says that if I want to be a Southern Baptist, I can be, and I should be able to perform the behaviors that my Southern Baptist faith prescribes. The negative component says that if I'm a Southern Baptist, I shouldn't be forced by law to go to confession, or pray to Mecca 5 times a day, or eat only kosher foods.

Assuming that most Americans value both of these components of their religious freedom, and value them highly, it stands to reason that there are some religious values that individual Americans have, but which should not guide their voting. For instance, Muslim Americans who share this value should not vote to force all women to wear Burkhas in public (or vote for politicians because they support laws of that sort), because it is inconsistent with the negative component of religious freedom. On the other hand, there are values that are primarily or entirely religious (e.g., anti-abortion values) which, though they are religiously-motivated values, can reasonably be said to trump the value of religious freedom. I suspect that most Americans who believe that abortion is murder feel that life is more sacred than absolute religious freedom*. So, in the case of burkhas, one probably should not vote according to one's specific religious value, but according to one's broader belief in religious freedom, while in the case of abortion, one should probably vote according to the specific religious value even if it conflicts with one's concept of religious freedom.

The question individuals have to ask themselves, then, is which religious values should and should not guide voting, given their belief in the the two components of religious freedom above? Which are more like the burkha issue, and which are more like abortion? There just happens to be an excellent example in contemporary American politics that can illustrate the difficulty in answering this problem: gay marriage. I, and many other secularists or liberal Christians are likely to feel that opposition to gay marriage, which is almost always motivated by religious beliefs, should not guide voting. When it does, it violates the negative aspect of religious freedom in a way that is more like the burkha example than the abortion one. Many conservative Christians may think otherwise. They may believe that the case of gay marriage is more similar to abortion than to burkhas.

The long of the short of all this is that the statement, "people should vote according to their values" is too broad, and in each case, we should look at the particular set of relevant values before determining which ones should guide our votes. The second lesson is that people can, and sometimes should be criticized for voting according to certain values, but it's likely that many of us will disagree about which cases deserve criticism, and which do not. Thus, the real lesson is that justifying one's vote by saying ,"I am just voting my conscience," or, "I'm just voting according to values," is just another way of saying, "You and I disagree." Furthermore, such appeals carry no more weight against criticism than mere disagreement, which is to say, none at all.

* Before anyone starts to wonder, I am vehemently pro-choice, and in this paragraph, I am simply trying to articulate what many anti-choice Christians may believe.

In This Case, I'm a Red-State Man

Would I ever vote for a blue-stater, you're wondering? That's hard to say. He or she would have to be a great candidate in all other ways.

Monday, December 20, 2004

Linguistic Restraint: The Case of "Fascist Theocracy"

What's even more important than discussing the differences between the U.S. and other nations, though, is the difference between the role of religion in American politics now versus the role of religion in America's past, and the potential problems we could face in the future. There is currently a relatively small, yet extremely vocal minority in America that longs to see a political system much closer to that of a country like Iran than the one we currently have. These people have their own hyperbolic rhetoric, with terms like "secular revolution," "judicially imposed atheism," and "Christophobia." In their minds, the country is not moving towards a fascist theocracy, but in the opposite direction, toward atheistic totalitarianism. As much as I would like to, I can't seem to find a reason to see the rhetoric of some on the left as more dangerous than this rhetoric from the right. They both have the effect of undercutting the possibility of intelligent discussion by contracting the conceptual space in which important distinctions can be made.

A recent example might help to illustrate my point. In a recent article by Bruce Walker entitled "The Nuclear Solution to Judicially Imposed Atheism," the following amendment to the Constitution is suggested:

Jason Juznicki has already written an excellent post on the substance of this proposal, and I have nothing to add to it. Instead, I want to use this as an example of the problems with the rhetoric on both sides, and on the left in particular. The suggested amendment is clearly reactionary, and to an absurdly unnecessary degree. There is no evidence whatsoever of a concerted effort of secularist judges to infringe upon the religious freedoms of anyone. Sure, some conservative Christians feel like judicial decisions which force the removal of religious symbols from courthouses, or disallow the teaching of their own creation myths in science classrooms, amount to infringements on their religious freedom, but these infringements, if they can even be called that, are minor relative to the rhetoric and proposed solutions some conservative Christians are using. The government, including the judicial branch, has made no attempts to curtail the rights of individuals to worship privately as they please, or even to remove such visible religious symbols as the references to God on coins. Once we've made such overstated accusations as "judicially imposed atheism," how do we begin to discuss government attempts to impose limits on private worship if and when they actually do occur?“SECTION ONE: The government of the United States holds this truth to be self-evident: that all people are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

“SECTION TWO: Religion, morality and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, shall forever be encouraged. The foundational principles of the American government are based upon the faiths of Christianity and of Judaism.

“SECTION THREE: When any judge of the United States or justice of the Supreme Court of the United States construes the Constitution contrary to the foregoing sections of this amendment, then when two thirds of the members of the House of Representatives concur, that officer shall be removed from office.

Fortunately for all of us, and those conservative Christians who are crying foul in particular, there are few people, if any, in the U.S. today who are calling for the government to infringe upon the rights of citizens to worship as they please. There are, however, people calling for a substantial increase in the role played by religion in the public sphere. Walker's proposed amendment to the Constitution is an excellent example of this. If such an amendment were to pass, then we would be right to express worry about theocratic tendencies in America. Yet, as Jason notes, amendments like this have absolutely no chance of passing in today's United States. This is because overall, the theocratic impulses of the American people and their government are at most extremely limited. Yet the distinction between an atmosphere in which such an amendment would have a chance of passing, and the current atmosphere in American politics, disappears when we describe our current situation as "fascist theocracy." How, then, are we supposed to combat the theocratic tendencies in some, if we can't articulate the distinction between a fairly marginalized political view and a genuine threat? Wouldn't it be more productive to use language that allowed for such distinctions?

For now, both those who feel we are in the midst of a theocratic revolution, and those who feel an atheistic one is well underway, are in the extreme minority. My impression is that to the average American, neither of these fears seems realistic. Yet I worry that the influence that those who use such claims to attract attention, and even those who genuinely believe them, might be growing. What would we do if these two ways of speaking about the direction of our country were to reach the level of national debate, or worse, to dominate it? That is a fear that I think is much more reasonable.

Sunday, December 19, 2004

A Plea for Suggestions

Reasoning: Mental Models

Mental models comprise what may be one of the most controversial and powerful theories of human cognition yet formulated. The basic idea is quite simple: thinking consists of the construction and use of models in the mind/brain that are structurally isomorphic to the situations they represent. This very simple idea, it turns out, can be used to explain a wide range of cognitive tasks, including deductive, inducitive (probabilistic), and modal reasoning. There are several ways of conceptualizing mental models, such as scripts or schemas, perceptual symbols, or diagrams. Here I am only going to deal with what mental model theories have in common in their treatments of human reasoning.

The idea that cognition uses mental models to think and reason is not a new one. "Picture theories" of thougth were common among the British empiricists of the 17th and 18th centuries, and were also held by many philosophers and psychologists in the first half of the 20th century (e.g., Wittgenstein's picture theory from the Tractatus). However, with the beginning of the cognitive revolution in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the computational metaphor of mind led to the prominence of propositional, or digital theories of representation and reasoning. Mental models returned to prominence in the 1980s because of their sheer predictive power. Study after study demonstrated that human reasoning exhibited certain features predicted by mental models, and not by propositional theories. Thus, for the last two decades, mental model theorists and propositional reasoning theorists have been locking horns and trading experimental arguments over how best to conceptualize human thought.

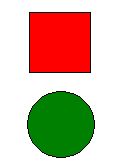

As I said before, the mental models view of mind is quite simple. For instance, the statement "The red square is above of the green circle" might be represented by the following mental model:

The model can be altered to fit any possible configuration. If the statement was more vague, we might construct several mental models to account for all of the possible interpretations. For instance, if the statement were "The red square is next to the green circle," we might construct multiple models with different "next-to" relationships, including one with the square to the right of the circle, one with it to the left, one with above, one with it below, and so on until all of the possible interpretations were represented. The difference between this representation and the propositional one1 are straightforward. The propositional represents the structure of the situation without preserving that structure in the form of the representation, while the mental model represents that structure through an isomorphic structure in the representation.

One problem with the way I've described mental models thusfar is that it might be tempting to see mental models synonymous with perceptual (particularly visual) imagery. However, not all mental models are perceptual images, and research has shown that perceptual imagery itself may be built on top of mental models. In addition, mental models can represent abstract concepts that may not be visualizable, such as "justice" or "good." The important aspect of mental models is not that they are or are not perceptual, but that they preserve the structure of the situations they represent, which can be done with perceptual images or non-perceptual representations.

To see how mental models work in reasoning, I'm going to describe mental model theories of three different types of reasoning: deductive/syllogistic, probabilistic, and modal. For each type of reasoning, mental model theories make unique predictions about the types of errors people will make. Hopefully by the end, even if you don't agree with the mental models perspective, the research on reasoning errors will have provided you with some new insights into the way the human mind works.

Deductive Reasoning

Recall the description of participants' performance in the Wason selection task from the first post. For the part of the solution that is identical with modus ponens participants answered successfully, but not for the part of the solution identical with modus tollens. According to propositional theories of reasoning, the best explanation for this is that people are in fact using modus ponens, or an equivalent rule, but not modus tollens. The mental models explanation differs in that it doesn't posit the use (or failure to use) either rule. Instead, people construct mental models of the situation, and use those to draw their conclusions. Here is how it works. Participants build a model of the premise(s) based on their background knowledge, and then come up with conclusions based on that model. To determine whether these conclusions are true, they check to see if they can construct any models in which it does not hold. If a conclusion holds in all of the models a person construct, then it is true. If not, then it is false.

In the Wason selection task, the problem is to determine which models result in the rule being true, and which result in it being false, and use this knowledge to decide which cards to turn over. In the version of the Wason task from the first post, the rule was, "If there is a vowel on one side of a card, then there is an odd number on the other side," and we had these cards:

There are various models in which this rule is true. They are the following:

VOWEL ODDHowever, only the first of these explicitly represents the elements mentioned in the rule, and given working memory restrictions, we're likely to only use the elements in the first model when testing the rule. If there is a vowel (e.g., E) on the visible side of a card, then there are two possibilities for the other side. In a mental model, they would be represented with the following:

CONSONANT EVEN

CONSONANT ODD

ODD VOWEL

ODD CONSONANT

EVEN CONSONANT

ODDIn some models (the ones with ODD on the other side) the rule is true, and in some (the ones with EVEN) it is false. Thus, the person knows that he or she must turn the card with the vowel over to test the rule. However, due to working memory constraints, we tend to consider only a small number of alternative models, and thus we're only likely to represent models that contain elements from our mental model of the rule. Since there is no EVEN in our model of the rule, we're unlikely to think that we need to turn over the card with the 2 showing, and because there is an ODD in the rule model, we are likely to mistakenly think that we need to turn over the 7. Things are actually a little bit more complex than this. It turns out that representing negations in situations like this (where the content of the models if fairly abstract or unfamiliar) is more difficult (because it requires the construction of more mental models) than representing positive situations, but for our purposes, it suffices to say that working memory makes it less likely to consider models that aren't easily derived from our model of the rule.

EVEN

To see better how this works, consider the following problems from Johnson-Laird et al. (1998)2:

Only one of the following premises is true about a particular hand of cards:Johnson-Laird et al. give the following explantion of participants' performance on this sort of problem:

There is a king in the hand or there is an ace, or both.

There is a queen in the hand or there is an ace, or both.

There is a jack in the hand or there is a 10, or both.

Is it possible that there is an ace in the hand?

For problem 1, the model theory postulates that individuals consider the true possibilities for each of the three premises. For the first premise, they consider three models, shown here on separate lines, which each correspond to a possibility given the truth of the premise:Here is another example from Johnson-Laird, et al. (1998):

king

ace

king ace

Two of the models show that an ace is possible. Hence, reasoners should respond, "yes, it is possible for an ace to be in the hand". The second premise also supports the same conclusion. In fact, reasoners are failing to take into account that when, say, the first premise is true, the second premise:

There is a queen in the hand or there is an ace, or both

is false, and so there cannot be an ace in the hand. The conclusion is therefore a fallacy. Indeed, if there were an ace in the hand, then two of the premises would be true, contrary to the rubric that only one of them is true. The same strategy, however, will yield a correct response to a control problem in which only one premise refers to an ace. Problem 1 is an illusion of possibility: reasoners infer wrongly that a card is possible. A similar problem to which reasoners should respond "no" and thereby commit an illusion of impossibility can be created by replacing the two occurrences of "there is an ace" in problem 1 above with, "there is not an ace". (emphasis in the original)

Suppose you know the following about a particular hand of cards:

If there is a jack in the hand then there is a king in the hand, or else if there isn’t a jack in the hand then there is a king in the hand.

There is a jack in the hand.

What, if anything, follows?

For which they give this explanation:

Nearly everyone infers that there is a king in the hand, which is the conclusion predicted by the mental models of the premises. This problem tricked the first author in the output of his computer program implementing the model theory. He thought at first that there was a bug in the program when his conclusion -- that there is a king -- failed to tally with the one supported by the fully explicit models. The program was right. The conclusion is a fallacy granted a disjunction, exclusive or inclusive, between the two conditional assertions. The disjunction entails that one or other of the two conditionals could be false. If, say, the first conditional is false, then there need not be a king in the hand even though there is a jack. And so the inference that there is a king is invalid: the conclusion could be false.The take-home lesson from all of this is that in deductive problems, working memory constraints that cause us to consider a limited number of mental models lead us to make systematic errors in reasoning, including those found in the original Wason selection task. It also explains why, when we place the Wason task in a familiar context (e.g., alcohol drinkers and age), we perform better. For these scenarios, we already have more complex mental models in memory, and can use these, rather than models constructed on-line for the specific task, to reason about which cards to turn over.

Probabilistic Reasoning

Reasoning about probabilities occurs in a way that is very similar to deductive reasoning. The mental models view of probabilistic reasoning has three principles: 1.) people will construct models representing what is true about the situations, according to their knowledge of them 2.) all things being equal (i.e., unless we have some reason to believe otherwise), all mental models are equally prob2bly, and 3.) the probability of any situation is determined by the proportion of the mental models in which it occurs3. If an event occurs in four out of six of the mental models i construct for a situation, then the probability of that event is 67%. However, because mental models are subject to working memory restrictions, they will lead to certain types of systematic reasoning errors in probabilistic reasoning, as they do in deductive reasoning. For instance, consider this problem 4:

On my blog, I will post about politics, or if I don't post about politics, I will post about both cognitive science and anthropology, but I won't post all on three topics.For this scenario, the following mental models will be constructed:

POLITICSWhat is the probability that I will post about politics and anthropology? If all possibilities are equally likely, the answer is 1/4. However, researchers found that in problems like this, people tend to answer 0. The reason for this is that in the two mental models people construct for this situation, there is no combination of politics and anthropology.

COG SCI ANTHRO

Another interesting and widely-studied example is the famous Monty Hall problem. For those of you who haven't heard of it, I'll briefly describe it, and then discuss it from a mental models perspective. On the popular game show Let's Make a Deal, hosted by Monty Hall, people were sometimes presented with a difficult decision. There were three doors, behind one of which was a great prize. The other two had lesser prizes behind them. After people made their first choice, Hall would open one of the doors with a lesser prize, and ask them if they wanted to stick with their choice, or choose the remaining door. The question is, what should participants do? Does it matter whether you switch or stay with your original choice? If you're not familiar with the problem, think about it for a minute, and come with an aswer before reading on.

Do you have an answer? If you're not familiar with the problem, the chances are you decided that it doesn't matter whether you switch. However, if this is your answer, then you are wrong. The probability of selecting the door with the big prize, if you stick with your original choice, is 33%. The probability of selecting the door with the big prize if you switch, however, it 66.6%. To see why this is, imagine another situation, in which there are a million doors to choose from. You choose a door, and Monty then opens 999,998 doors, leaving one more, and asks you if you want to choose? In this situation, it's quite clear that while the chance of selecting the right door on the first choice was 1/1,000,000, the chance of the remaining door being the right one are 999,999/1,000,000.

When participants have been given this problem in experiments, 80-90% of them say that there is no benefit to switching. They believe that the probability of the remaining door containing the big prize is no greater than the probability of the door they've already chosen containing it (the so-called "uniformity belief")5. In general they either report that the number of original cases determines the probability of success (probability = 1/N), so that the probability in the first choice is 1/3, and in the second choice it is 1/2, or they believe that the probability of success remains constant for each choice even when one is eliminated6. Recall the three principles of the mental models theory of probabilistic reasoning. According to these, people will first construct mental models of what they know about the situation. In the Monty Hall problem, they will construct these three models:

DOOR 1 BIG PRIZEEach of these models is assumed to be equally probably, and the probability of any one of the models being true is 1 over the total number of models, or 1/3. After the first choice has been made, and one of the other doors eliminated, people either use this original model, in which case they assume that the probability of the first door chosen and the remaining door are both 1/3, or they construct a new mental model with the two doors, and thus reason that the probability for both doors is 50%. Their failure to represent the right number of equipossible models, and therefore reasoning correctly, is likely due to working memory straights, and research has shown that by manipulating the working memory load of the Monty Hall problem, you can get better or worse performance7.

DOOR 2 BIG PRIZE

DOOR 3 BIG PRIZE

Modal Reasoning

The mental models account of modal reasoning should be obvious, from the preceding. To determine whether a state of affairs is necessary, possible, or not possible, one simply has to construct all of the possible mental models, and determine whether the state of affairs occurs in all (necessary), some (possible) , or none (not possible) of the models. There hasn't been a lot of research on modal reasoning using mental models, because it is similar to probabilistic reasoning, but people's modal reasoning behaviors do seem to be consistent with the predictions of mental models theories.In particular, people seem to make assumptions of necessity or impossibility that are incorrect, due to the limited number of mental models that they construct (e.g., in Johnson-Laird et al. (1998)'s first problem described in the section on deductive reasoning).

So, that's reasoning. There are all sorts of phenomena that I haven't talked about, and maybe I'll get to them some day, but for now, I'm going to leave the topic of reasoning. I hope Richard is at least partially satisfied, and maybe someone else has enjoyed these posts as well. If anyone has any further requests, let me know, and I'll post about them if I can.

1 There are various ways of describing propositional representations. A common way of representing the sentence "The redsquare is above the green circle" is ABOVE(RED(SQUARE),GREEN(CIRCLE)).

2 Johnson-Laird, P. N., Girotto, V., & Legrenzi, P. (1998). Mental models: a gentle guide for outsiders.

3 Johnson-Laird, P.N., Legrenzi, P., Girotto, V., Legrenzi, M.S., & Caverni, J.P. (1999). Naive probability: a mental model theory of extensional reasoning. Psychological Review, 109(4), 722-728.

4 Adapted from Johnson-Laird, et al (1999).

5 See, e.g., Granberg, D., & Brown, T. A. (1995). The Monty Hall dilemma. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 711–723; Falk, R. (1992). A closer look at the probabilities of the notorious three prisoners. Cognition, 43, 197–223.

6 Shimojo, S., & Ichikawa, S. (1989). Intuitive reasoning about probability: Theoretical and experimental analyses of the “problem of three prisoners.” Cognition, 32, 1–24.

7 Ben-Zeev, T., Dennis, M, Stibel, J. M., & Sloman, S. A. (2000). Increasing working memory demands improves probabilistic choice but not judgment on the Monty Hall Dilemma. Paper submitted for publication.

Saturday, December 18, 2004

A New Definition of "Bad"

The evolutionists insist the dinosaurs lived millions and millions of years ago and became extinct long before man walked the planet.By the way, I love WorldNetDaily. Where else can you get laughs like this?

I don't believe that for a minute. I don't believe there is a shred of scientific evidence to suggest it. I am 100 percent certain man and dinosaurs walked the earth at the same time. In fact, I'm not at all sure dinosaurs are even extinct!

Think of all the world's legends about dragons. Look at those images. What were those folks seeing? They were clearly seeing dinosaurs. You can see them etched in cave drawings. You can see them in ancient literature. You can see them described in the Bible. You can see them in virtually every culture in every corner of the world.

Trying Juveniles as Adults

The first item reports the arraignment of a 16-year-old student for murdering a classmate with a shotgun. My wife and I do not know the boys, but we have grieved for them and their parents since the incident was first reported. Our grief was only deepened by the story linked here, reporting that the accused will be tried as an adult.There are people arguing from both sides (those in favor of trying children as adults, and those opposed to it), and some of the comments are very good. For instance, some have cited neuroimaging research that shows juvenile brains to be less developed in the areas related to decision making and reasoning about the consequences of one's action. The most interesting comment, to me, is the one by Rob Kar. He writes:

I am currently teaching a course on contract law at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, and one of the common law defenses to a breach of contract claim that I teach is--as several have noted--minority. (With some exceptions, minors are typically allowed to disaffirm a contract entered into as a minor.) The typical rationale for this defense is well captured by a number of things people have said here: minors are often thought somehow less than fully capable of (i) making appropriate judgments about what to do and/or (ii) conforming their behavior to those judgments. Minority is also typically a defense (or at least a mitigating factor) in criminal prosecutions. And I think it's often assumed that whatever capacity is lacking in one case is the same as what is lacking in the other.His argument, in essence, is that if contract law assumes that children are not fully capable of making rational judgements and "conforming their behavior to those judgements," why should criminal law assume that they are? Thus, toward the end of the comment, he writes: